The introduction of a single European currency was for many member states of the European Union a logical next step in a single market. With assumed improvements for trade, employment and wealth distribution, the euro was expected to bring all the different European economies closer together through the convergence of labour, fiscal, social and economic policies. Further political integration would be triggered and the ultimate ideal of unity and longstanding peace could be reached. But 15 years after the introduction of the euro, the reality is quite different. Instead of more, we see less solidarity among European member states. At the same time, there are rising trends in inequality, unemployment and low paid jobs – trends caused by the financial crisis, some might say, but such analysis overlooks several important details. In this long read we dive into those details and ask the question: what has the single currency brought us exactly?

About our living analysis on the eurocrisis

This first article looks at what has become of the ideals of the Eurozone through some reality checks.

The second article, ‘Debts and imbalances – The making of the euro crisis‘, focuses on the economic analysis of sovereign debt and imbalances within the Eurozone.

The ideal of longstanding peace and political stability

This article is the first in a series for a better understanding of the crisis in the Eurozone. This first article looks at what has become of the ideals of the Eurozone through some reality checks. The second article Debts and imbalances (expected January 5th) focuses on the economic analysis of sovereign debts and imbalances within the Eurozone. The third part, which will be published soon afterwards, shows that varieties of alternative policies are available and feasible.About our living analysis on the eurocrisis

‘We could be sentimental now the Drachma has gone, with her 2,650 years the oldest currency of Europe,’ the former Prime Minister of Greece Costas Simitis said during the introductory celebrations of the euro in the early hours of 1 January 2002, ‘But for Greece this is an incredible historic moment: now we belong to the real Europeans’. The Dutch Prime Minister Wim Kok, who celebrated the introduction of the euro in Maastricht, the currency’s city of birth in 1992, emphasized that it would bring longstanding peace and political stability to Europe.Video - The adoption of the Euro (multilingual)

If you read reports about the celebration of the euro at that time, you can see overwhelmingly the dream of European unity and peace. Former German Chancellor Helmut Kohl explains this optimism for the euro in an interview in 2002: ‘Nations with a single currency never went to war against each other. A single currency is more than the money you pay with. I wanted to bring the euro because to me it meant the irreversibility of European development… for me the euro was a synonym for Europe going further.’ Speech at The Hague – 19 January 1999 at the 10th Annual Dinner of the Foundation for the Preservation of Nieuwspoort Ladies and gentlemen, some of you will perhaps be expecting now a detailed presentation of the German programme for its presidency during the coming six months with explanations about the employment pact under consideration, about the chances for the solution of Agenda 2000 and about our ideas for a swift continuation of admission negotiations. I will disappoint you. These subjects will surely dominate the Euro-political debate over the coming months. But it seems to me however that the forthcoming fundamental changes in our Euro-political understanding are of much greater and more far-reaching importance. I am convinced that we are in the midst of a European political phase of change and require new models for the future. It is a fact: the European political language of the founding years is no longer understood by many. The aim to secure lasting peace between member states by economic integration has been achieved and has become for all of us a matter of course. In view of the high degree of common economic bonds, the growing common cultural understanding and trust and the close political co-operation, just the thought of a return to nationalism and rivalry seems to be absurd. This is probably the greatest merit of the European political post-war history. We have to safeguard and this heritage and safeguard it for the future.Speech by German Chansellor Gerhard Schroder about the advantages of the Euro

A single currency was also meant to control Germany as the economic powerhouse of Europe – something that was essential according to European leaders, especially France, during the re-unification process of Germany in 1989–1990. The German magazine Der Spiegel cites the minutes of discussions it has seen between the former French president Francois Mitterand and the then German foreign minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher in the late 1980s and early 1990s as proof of a secret pact to dump the Mark as the price of re-making a single nation. ‘Germany can hope for the reunification only if it stands in a strong community’, the then French president said. ‘The current policies of the Federal Republic are putting a brake on the economic and monetary union.’ The European institutions such as the Brussels-based European Commission, European Council and Eurogroup of finance ministers, plus the Frankfurt-based European Central Bank were very much interconnected from the start of the Monetary Union. This is what Erik Jones, Professor and Director of European Studies at The Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies describes as the ‘Brussels–Frankfurt consensus’, which has replaced the France-German as, and which underpins Europe’s single currency and the basis of the idea of sound finance (e.g. aiming for a budget surplus) and stable money (e.g. low inflation rates). ‘It was the logical response to the liberalization of international financial markets; it was the price for German participation; and it was the hegemony of neo-liberalism in the battle of ideas,’ Jones writes. But after the financial crisis the ‘German economics community is openly discontent with the ECB; the ECB and the European Commission are promoting different agendas; and the member states are clearly divided as to what should be the solution.’ Please find some other examples and links to publications on the power of Germany within the EU: Next to the ideals of peace and controlling German economic supremacy, many economic reasons were brought forward in favour of the single currency. Harvard University economist Jeffrey Frieden wrote back in 1998 (pdf): ‘Big corporations and banks believed that removing the uncertainties of currency fluctuations would help them realize the full promise of a single European market and give them a large effective home base from which to confront outside competitors.’ And it was believed that this promise would benefit all countries within the Eurozone. Countries with traditionally high inflation, like Italy and Spain, would benefit from greater inflationary discipline due to the introduction of a common interest rate that the European Central Bank (ECB) would set for the whole Eurozone. The idea was that low inflation in these countries could be realized through adaptation to a stringent budgetary regime in combination with interest rates that are lower than their economies would require due to the ECB’s common interest rate policy. Low inflation means stable prices and wages, and, therefore, could benefit economic activities in all member states. In the mid-1990s in the Netherlands the former government coalition of Social Democrats and Liberals claimed that the single currency would boost economic growth. ‘At the end of the day, all Dutch consumers will benefit from the elimination of costs of conversion; hedging; international pricing opaqueness; exchange rate instability; and lack of unity and credibility of monetary policy coordination in the current EMS [European Monetary System]. Opportunities for trade and market shares for Dutch producers will grow. Foreign investments in the Netherlands will also grow’, said Jos de Beus who wrote about how the Dutch Social Democrats embraced the euro in the 1990s. Read also the Europe Lecture 1999 by Hans Tietmeyer who was President of the Deutsche bundesbank (1993-1999) It became a popular argument in most Northern European member states, also among trade unions and employer organizations: the single currency would increase trade, employment and living standards, while also equalizing prices and wages. The Dutch trade union CNV, for example, was openly optimistic about the introduction of the euro. ‘What will change with the Euro? The Guilder and Mark will be a bit less strong, and that is good for us,’ was their message in Dutch newspaper NRC Handelsblad, referring to the historic opportunity to improve Dutch and German competitiveness in Europe. Although many trade unions were merely positive about the euro, in order to prevent possible downward competition in relation to wages and working conditions, some European trade unions agreed upon a set of joint bargaining guidelines. In September 1998, Belgian, Dutch, German and Luxembourgian trade unions adopted a joint declaration stating the strong need for close cross-border coordination of collective bargaining under an EU Economic and Monetary Union. (Source: Eurofound) A single currency also means the handing over of power to the European Commission and other centralized European institutions like the European Central Bank. National budgetary rules for example were established within the Stability and Growth Pact, setting the threshold for the annual government budget deficit of member states at 3% of GDP. Countries gave up the power to revalue their national currencies, as well as their central banks’ influence over interest rates. In order to work effectively, a single currency ultimately means the conversion of economic, social, fiscal and labour policies between member states. In other words: a political union was necessary for the monetary union to effectively deliver stability, growth and employment. In 1998, EU member states agreed to strengthen the monitoring and coordination of national fiscal and economic policies to enforce the deficit and debt limits established by the Maastricht Treaty. Read here the original agreement that was called the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP). As an example, it set a threshold for annual budget deficits for member states at 3% of their GDP. After the financial crisis in 2012, the SGP was changed with the inclusion of the Six Pack, which increased centralized monitoring of both budgetary and economic policies under the European Semester. As a failure to respect the SGP’s preventive or corrective rules, countries may ultimately face sanctions. For member states sharing the euro currency, these sanctions could take the form of warnings and ultimately financial sanctions including fines of up to 0.2 % of GDP if they fail to abide by either the preventive or the corrective rules. The fines could more than double to 0.5 % of GDP if they repeatedly fail to abide by the corrective rules. In addition, all member states (except the UK) could have a suspension of commitments or payments from the EU’s Structural and investment funds (e.g. the European Regional Development Fund, the European Social Fund, the Cohesion Fund, the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development and the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund). (Source: European Commission) The reality is that national governments have never been keen to limit their sovereignty in favour of such a political union. The introduction of the euro could have changed that, but back in the 1990s national governments decided that the monetary union could go ahead without a political union. The idea was that a monetary union would progressively increase the convergence of member states’ economic, fiscal, social and employment policies after its establishment. There was no necessity for a real political union, therefore, according to the member states. An optimal currency area of converging policies and declining cultural and language barriers to improve the free flow of workers within the single market ‘[would] be increasingly fulfilled over time as citizens and governments learn to live with a common currency,’ wrote economists Richard Baldwin and Charles Wyplosz.1 Thus, the ideal of a political union became a vague and long-term commitment, while at the same time the euro had already became a reality. The result was that member states did not really attempt to grow closer to each other through converging policies. Now the idea of a political union is back on the agenda because of the financial and economic crisis in the European Union. As Italian Finance Minister Pier Carlos Padoan, backed by French President Francois Hollande, puts it, ‘to have a full-fledged Economic and Monetary Union, you need a fiscal union and you need a fiscal policy’. He suggests, for example, a common unemployment-insurance programme. A report in late June 2015 issued by the President of the European Commission Jean-Claude Juncker, President of the European Council Donald Tusk, and the presidents of the ECB, the European Parliament and the Eurogroup of Eurozone finance ministers, also recommended establishing an EU-wide bank deposit insurance system and a common European treasury. The political union never really came about. After the euro was introduced, the member states continued their own economic and fiscal policies. Since then, each of the initial 16 Eurozone countries has behaved as if it still managed its own currency. Each country went its own way when it came to lowering or raising taxes, borrowing money or cutting labour costs, almost as if it were expected not to take the other Eurozone countries into account. For example, Ireland continued to stimulate the relocation of the headquarters of multinational corporations to their shores due to low corporation taxes, without regard for the impact of its actions on other member states. And while, for example, Spain’s workers saw their salaries increase thanks to cheap capital inflows and a construction boom, Germany stabilized its labour costs between 1996–2005 and even lowered them significantly in the years 2005–2008 as a result of implementing labour market reforms, deregulation and a low level of productivity growth. Germany was not alone, countries like the Netherlands, Austria, and Finland all encouraged wage growth moderation and flexible working conditions. In doing so, they started a race to the bottom to increase competitiveness through reforms in labour market policies and fiscal policies. But Greek economist Costas Lapavitsas points out: ‘Germany often accuses Greece – [Wolfgang] Schauble for instance does – that Greece has been living beyond its means. It’s true. But Germany has also been systematically living below its means, and this is how exports are generated, not because of technology, productivity and all that. That’s why it is so successful.’ And there is truth in his vision. In a monetary union, almost every economic decision has consequences for the partner countries. When labour costs fall in Germany, business owners and workers are directly affected in even the most remote corners of Portugal and Ireland due to increased competitiveness and without the compensation mechanism of exchange rates. In other words, in a monetary union it cannot be a bad thing to live above your means and a good thing to live below. The real rule must be to live by your means, explains Lapavitsas: ‘So Germany has not kept [to] the rules and the price is paid by the German people [in low wages and job insecurity].’ The fact that Germany is a part of the euro crisis problem has been wide spread among experts. Read the following examples: Striking as well was that European governments violated the union’s self-imposed rules about solid budget practices right from the start: it was not just Greece and Portugal, but Germany and France that were among the first countries to violate these rules. The offenders seemed to believe that things would work out in the end, and that others would foot the bill. From 2003–2005 the German and French governments’ budget deficit exceeded 3% of their GDP. The European Commission – then led by the former Italian Prime Minister Romano Prodi – had the power to fine these countries. But the finance ministers of what was then the 15 Eurozone member states gathered in Brussels and voted the Commission down. They voted not to enforce the rules they had signed-up to, which were designed to protect the stability of the single currency, and to let France and Germany off, the two most powerful nations within the Eurozone. In an interview with the BBC Romano Prodi remarked later: ‘Clearly, I had not enough power. I tried and they [the finance ministers of the Eurozone countries] told me to shut up.’ Instead of being fined, France and Germany were given more time to bring their budget deficits under control. The two countries were told to end their excessive budget deficits by 2005 at the latest. Paris believed that the EU’s financial rules did not take into account periods of low growth and should be more flexible to allow countries to use a budget deficit to increase GDP growth and their budgets. Berlin believed that it needed more time to realize its labour market reforms. They both emphasized that the threshold is arbitrary and some expenses at moments of low economic growth could help economies to recover and give them political space to implement difficult reforms. However, the Commission said that France had not made any effort to comply with the Stability and Growth Pact – and German efforts to do so had been ‘inadequate’. The Commission stated in 2003: ‘Only a rule-based system can guarantee that commitments are enforced and that all member states are treated equally.’ Ironically, now Germany is among the countries that propose to implement such enforcements on all its member states, while the overspending at the start of the 2000s helped Germany to get through a painful transition. The French idea that the German economic powerhouse could be controlled within a monetary union has failed. On the contrary, the euro was the springboard that enabled Germany to amass more economic power as it developed into the main creditor for other Eurozone countries. It now is the most powerful member state and is not working together with France to solve the problems in other member states, but with the European Central Bank based in Frankfurt and the International Monetary Fund. What happened was that Northern European countries (e.g. Germany, Finland, the Netherlands) could increase their export-led economies based on moderate wages, flexible labour markets and an undervalued euro. As the second article in this series will explain in more details, the trade surplus in these countries triggered cheap capital inflows into Southern European economies. In the years before the economic and financial crisis started in 2008, this was not seen as much of a problem by both sides. First, the creditors, the European bankers who were lobbying in favour of the introduction of the euro, were pleased. They welcomed new ways to make money on loans. To quote economic commentator Steve Randy Waldman from his blog Interfluidity: ‘The European financial system was architected to make lending to Greece — and Spain and Portugal and Italy — a money machine for bankers with little career risk over a medium term.’ European bankers could earn money with risky loans to weaker Eurozone countries, as the European banking regulations attached zero risk weight to all the public debt held by individual Eurozone member states, rendering it nearly costless for banks to simply manufacture deposits to purchase the public debt (also called sovereign debt) of Southern European countries. Eurozone sovereign debt was default-risk-free as a regulatory matter and currency-risk-free from the perspective of Eurozone banks. As such, the euro opened up a capital flow within the Eurozone benefitting the financial sector. Why has it been assumed that Eurozone member states are default risk-free? Why is this important to understand the euro crisis? Going default means that a country cannot pay back its debt obligations plus interest costs to its creditors. No developed country after World War II has ever defaulted on its debts, so assuming that the chance of a default would be nil is financially viable. The creation of a single currency convinced the financial sector and regulators that government borrowing was now a very safe investment across the Eurozone because countries were no longer able to nominally devalue their currency. Devaluation is risky for foreign creditors as this will mean that the value of debt will be reduced without any repayment. Therefore, the Eurozone made it less risky for European banks to give loans in other Eurozone countries. Furthermore, the costs of borrowing for many governments such as in Greece, Spain and Italy fell to historically low levels because all Eurozone countries paid the same interest rate on their debts. Yet many European countries did partly default in the past due to inflation and devaluation. With the euro, member states could not resort to devaluing their currency or printing money to solve their problems. Therefore, the default risk-free assumption masked risky cheap loans to Southern European countries. European economists Josef Korte and Sascha Steffen argue that deeming all sovereigns’ as without risk could cause distortions that could make the system riskier. Banks end up accumulating more government debt, both from their own country and other European governments, which makes it even riskier to allow a country to default and trigger a new Eurozone financial crisis. Investors now differentiate within the Eurozone. Greece and Spain pay far more interest rates on their bonds versus Germany and the Netherlands because they are now assumed riskier. Even France has seen the amount owed on its bonds rise to relatively the same rate as Germany. So far, governments have chosen to pay back their debt obligations with spending pledges – particularly pensions – rather than imposing pain on creditors. The debtors on the receiving end of the capital stream were blind, as property prices rose and economic growth was high in countries like Spain and Greece. That this growth was based on a speculative bubble, became clear soon after. The financial crisis of 2008 changed it all. Now they had to play the game of the creditor countries, whose first reflex was to reduce the risk of their own banks. For example, studies show that 90% of the bailout money was used to pay the debts that private European banks had in Greece with public money. Creditor countries put the blame on weak governance and corruption as the main cause of the debt-crisis, ignoring faults within the financial system. The result was a one-size-fits-all solution towards recovery of internal devaluation, proclaimed by the creditor countries, together with the IMF, European Commission and European Central Bank. This recovery strategy forced debtor countries to lower labour costs and wages in order to increase their international competitiveness, as devaluating their own currency was impossible. Their governments, therefore, had to increase VAT (expenditure tax) and reduce payroll taxes including national insurances. This left overall tax intake the same, but reduced the cost of hiring labour, which was assumed to be good for their international competitiveness. Secondly, the government had to reduce public sector wages and put pressure on other wages to decrease. The result was public spending cuts, lower wages, more flexible labour markets and lower pensions. The recovery pegged firmly to increasing international competitiveness, rising exports and austerity policies. At the same time, this path to recovery was an attack on European welfare states – one that had already started in the 1980s in the process to form a single market, but accelerated with this policy of recovery. Decision-making in the EU is captured politically. As economist Willem Buiter showed, there also exists a ‘cognitive capture’. He borrowed this term from psychology (also called ‘cognitive tunnelling’) where it describes the state in which people can become so focused on one thing that they miss the whole picture entirely. Politicians, public institutions and regulators have become one with the market forces by using the same vocabulary, the same models and hiring the people that all have been taught in the same economic theory of leading business schools. Philosopher Santiago Zabala expresses it this way: ‘The economists of the troika are not imposing violent austerity measures simply to politically dominate the European nations but rather to exclude any competing existential project, that is, any alteration to the troika’s vision of “the market”.’ According to Zabala, the EU prefers ‘intellectuals who submit “reality to reason” rather than fighting the ongoing exclusion of the most vulnerable citizens by those in power.’ Thus, for the benefit of the EU, its citizens ‘must submit to measures that inflict social injuries’. In that perspective, it is also interesting to quote Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben. His observations conclude that being in a crisis has become a motto for modern politics, and that it has become part of normality in every segment of modern life. When a crisis was related to a decisive moment and judgement at a particular time, the present understanding of crisis ‘refers to an enduring state. So this uncertainty is extended into the future, indefinitely’, writes Agamben. Therefore, according to Agamben, ‘today’s crisis has become an instrument of rule. It serves to legitimize political and economic decisions that in fact dispossess citizens and deprive them of any possibility of decision.’ In such circumstances the debate about an alternative for Europe can be put aside easily with the excuse that there is no time for experiments during a crisis, but without obligation to mention when the crisis is over. As a result, after more than 14 years of the euro, solidarity between countries and between citizens is at one of the lowest points in modern European history. This is well illustrated by the Greek bailout negotiations par excellence. For example, the debate about a new bailout deal at the start of 2015 went on for many months and was portrayed in Northern European media mainly as the ‘prudent’ Dutch, Germans, Fins and Austrians against the ‘irresponsible’ Greeks, Portuguese and Spaniards. But it is the Northern European countries, especially Germany, that benefited from the sovereign debt-crisis in Southern European countries due to lower interest payments on their own debts. Research from the Halle Institute for Economic Research shows that the debt crisis resulted in a significant reduction in German bond rates, yielding interest savings of more than EUR 100 billion (or more than 3% of GDP) during the period 2010–2015. To quote Jurgen Habermas, a great European thinker: ‘[The] technocratic hollowing out of democracy is the result of a neoliberal pattern of market-deregulation policies. The balance between politics and the market has come out of sync, at the cost of the welfare state, its citizens, and on behalf of a small percentage of the population that forms part of the economic elites and big shareholders.’ To understand the long term trend of European declining welfare states and increasing inequality, you can read more on the topic in the forthcoming publication Unequal Europe: How Regional Integration Reshaped the Welfare State and Reversed the Egalitarian Turn written by Jason Beckfield. Beckfield’s book is an accumulation of his earlier research and ‘develops the argument that European integration has generated, diffused, and enforced new rules of the political-economic game. These new institutional arrangements have reconfigured European capitalism, and in turn have fundamentally altered the stratification structure of Western Europe.’ See his earlier publication The End of Equality in Europe? for more information. Hence, the building blocks of the monetary union have worked as accelerator of mistrust and anti-solidary sentiments. European politicians and civil servants, bankers and financiers have all turned a systemic problem of financial architecture into a dispute between European nations. This was the opposite of what European policy-makers had always claimed the euro would bring; they said that a unified Europe would be forged one crisis at a time, which we would solve as Europeans together, not as nations in conflict. The ideal of a single currency that would generate wealth distribution within the borders of its member states can also be challenged. The single market, and with it the introduction of the single currency for most member states, highlights a rise in income inequality, with the highest increase in Spain, Ireland, Slovenia, Estonia, Greece and France between 2007–2010. Many blame the financial crisis for this rise, others austerity policies. But none of these views capture the whole picture. Instead, the cause has to be understood in the context of the continuing widening gap between rich and poor in the last three decades in all European member states, according to the OECD income distribution database. The crisis and the chosen recovery strategy only exacerbated income inequality after 2008. Income inequality in Europe is on the rise but the picture is diverse. Greece is the only EU country that saw a decline in the last 25 years in inequality, according to the OECD report Divided We Stand. The countries that remained stable include France, Belgium and Hungary. In all other countries, there is a long term increase of income inequality. Inequality is the highest in the UK, Portugal and Italy where 10% of the rich have an average disposable income more or less than ten times more than the poorest 10%. In countries like the Netherlands, Germany, France and Greece, the richest group has around seven times more than the poorest. Countries with the lowest inequality are the Nordic countries, Belgium and Austria with a rate of around 5.5. All European countries still have a low income inequality rate compared with emerging economies and the US, where the richest 10% earn 15 times more than the poorest 10%. The combination of an increasing inequality and a struggling middle class only increases the feeling among Europeans of economic injustice. The perception that a relatively small group is gaining money when the majority is not increases the general dissatisfaction in society. However, increasing disparities due to economic growth was not long an issue in economics and European policy in the last 25 years. The focus on growth and low inflation was enough for economic development. This focus has remained hidden up until recently with the release of the best selling book Capital in the 21st Century by French economist, Thomas Piketty. The book reveals that advanced economies are heading to an unhealthy situation considering most of the wealth is in the hands of a small elite. As inequality and GDP per capita are correlated for the European countries with higher purchasing power per person (meaning lower inequality rate of that country), the trend of higher inequality could have consequences for future economic growth. According to influential IMF economists Andrew Berg and Jonathan Ostry, that is exactly what is happening: high inequality will shorten growth duration. They recently wrote in their expert opinion for The Broker: ‘Our analysis should tilt the balance towards the long-run benefits—including for growth—of reducing inequality.’ The growing evidence only points to the fact that something must be done to fight against the rise of inequality. The question remains though of how to do it. And there is an increasing debate this. The OECD report is clear: ‘Any policy strategy to reduce the growing divide between rich and poor should rest on three main pillars: more intensive human capital investment; inclusive employment promotion; and well-designed tax/transfer redistribution policies.’ As The Broker has shown in its different dossiers, deliberate policies to increase international competition, deregulate labour markets, stimulate the financialization of the economy, and curb welfare states and social protection – all policies that can be tracked back to the European economic strategy to accomplish a single market – have had a huge impact on inequality. These policies and economic strategies have not only decreased the prospects of the lower economic classes, but have also had an impact on an increasingly struggling European middle class, which was the beacon of European integration in its early years. The Broker published dossiers on the European middle class in April 2015 and on Employment in March 2014. The Middle Class dossier reveals that there is an increasingly struggling middle class in Europe. This trend could be recognized though in most EU countries before the Eurozone crisis even started. The size of the middle classes were measured by income level and stabilized and even declined in most European countries after the mid-1990s. They have been struggling to find typical middle class jobs because better jobs have hardly been created for the middle income group. Economic and financial globalization and flexibilization of the labour market not only reduced upward job mobility for a smaller group of workers, the European middle class also has become more vulnerable to economic shocks. This trend fits in the conclusions from The Broker’s Employment dossier. It has become far more difficult within our current globalized world, dominant economic models and logic on whether the single market and a sole currency can create enough quality jobs. Precarious work is on the rise and only has risen more steeply due to the economic and financial crisis. (See also the paper on precarious work that The Broker issued in November 2014.) It is the economic model, logic and political strategy related to market liberalization that shaped the single market and, with it, the next step of realizing the single currency, which has increased inequality and lowered wages throughout Europe. Indeed, it is true that the European Commission celebrated 10 years of the euro by declaring that between 1998 and 2008 unemployment in the Eurozone decreased by 15%. However, investigation of the details exposes some worrying trends. In Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium and France, countries that adopted more flexible labour markets and wage moderation policies than other member states, jobs were mainly created at the low end of the labour market, including low-paid self-employment jobs, but not for the middle classes, increasing the divide between the middle classes and those better off. In Spain, Portugal and Greece employment increased for all economic groups, also the middle classes, but only because the influx of cheap capital resulted in a construction boom and speculative bubble. Joaquín Almunia, the former Commissioner for Economic and Monetary Affairs, writes in his foreword: ‘the euro is a keystone of further economic integration and a potent symbol of our growing political unity. And for the world, the euro is a major new pillar in the international monetary system and a pole of stability for the global economy.’ This quote was stated at the European Commission, EMU@10 Successes and challenges after ten years of Economic and Monetary Union event in May 2008. Consequently, the decline in employment after 2008, increase in precarious work and increase in poverty levels in Europe are now more structural embedded in the economies of EU member states. Pointing the finger only at the financial crisis and proclaiming a strategy of going back to business as usual is not a suitable strategy to reinvigorate employment. There is increasing recognition among economists that there is no way back to high growth, investment and productivity using existing monetary and economic models. Teodora Tchipeva – ‘policies should be strengthened along flexicurity principles so as to strengthen the upward mobility of the most vulnerable workers. In particular, adequate social protection combined with efficient activation policies (ALMP), skill formation and removal of obstacles to intra-EU labour mobility (including increased cross-border portability of pensions and other social security benefits) can be envisaged in this respect. The European Social Fund and the European Globalization Fund provide support to facilitate workers’ adjustment. Nevertheless, not all workers will have the ability to upgrade their skills to meet the requirements of the new knowledge- and technology-intensive activities and will remain employed in jobs that are subject to international competition from countries with lower quality standards for jobs. In such cases a minimum floor for job quality could be set by appropriately designed labour market institutions in close collaboration with social partners. A level playing field with trading partners should also be assured by including provisions in Free Trade Agreements covering minimum working conditions, enforcing national labour laws, and monitoring and enforcing labour standards.’ Jorg Peschner – ‘Unless we do not give in to the pressure to generate necessary higher productivity gains only through deepening into capital (rationalization), there is only one socially sustainable policy response to the challenge: human capital formation through skills development and higher education. Today’s coexistence of structural unemployment with skills scarcities in many sectors will certainly be aggravated once the entire workforce shrinks – unless Europe generates the very skills supply that sources say will be increasingly demanded by businesses all over the globalized world.’ Javier Andres – ‘The combination of wage flexibility and human capital accumulation is the key to success in this endeavour. Human capital accumulation – reforms in schooling and apprenticeships, contracts, active labour market policies – is the way to sustain productivity growth, to incentivize firms to further R+D investment, to achieve higher earnings and more stable labour careers. But this may take time, especially for low-skilled workers, and it has to be complemented with sufficient wage flexibility to facilitate the employment of those workers who suffer the competitive pressure of emerging economies as well as those looking for their first job. Wage flexibility is also needed to reallocate capital and labour to dynamic industries and to prevent further job losses in firms that suffer temporary falls in demand. Better skills and higher employment will help to avoid further increases in income inequality, although additional wage flexibility may have the opposite effect. Reducing inequality and tackling unemployment are not conflicting objectives in the long run, but they may appear so in the shorter term.’ John Grahl – ‘General loss of social control over employment since many aspects of control, for example over social insurance or working conditions, have depended on a relatively stable and continuous relationship between the two parties to the employment relationship. At least in the immediate future there seems no prospect of restoring the stability of the past and therefore, additional steps are necessary to protect the many workers in situations where the employer is difficult to identify, where the immediate employer is unable to meet the standards required or where the self-employed status of the worker means that there is no formal employer… Three types of policy will be suggested as responses to this situation. Firstly, it is sometimes possible to enforce worker rights without asserting a claim on an immediate employer…some worker rights might be made the responsibility of the government; rights to training and retraining could be examples here…Secondly, and as a reinforcement of these more widely enforceable labour rights, there needs to be a strong assertion of the supply-chain responsibilities of large enterprises. Legislation is almost certainly required to enforce genuine CSR: companies with substantial market power over supplier and businesses must be made responsible for the labour they use, not just for the labour they employ.’ With unsustainably high debt levels in many European countries, and with the lowest ECB interest rates for many years (of nearly zero per cent), there is little room for stimulating economic activities by increasing public spending and lowering interest rates. This is what in economics is called ‘secular stagnation’. What the single market had already started, was accelerated by the introduction of the euro: a race to the bottom with limited policy space for countries to stimulate growth through country-specific monetary measures. It is clear that ideals about a single currency – from unity, to a more effective single market, job creation and wealth redistribution – have not materialized. Yes, the economic and financial crisis has made things worse for many Europeans. But the trends that created the current sovereign debts in Europe are the result of the policy and strategy underpinning the economic and monetary architecture of the Eurozone. Trends like the rise in inequality and job polarization are also the result of deliberate choices based on ideals of the economic model of market liberalization, which were incorporated into policies that started with the single market and accelerated with the introduction of the single currency. Former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher famously and repeatedly said in the 1980s ‘there is no alternative’ for our economic growth model. In the early 1990s, Francis Fukuyama’s book The End of History and the Last Man similarly argues that liberal democracy had triumphed over communism and that the historic struggle between political systems was over. Both economic liberalism and liberal democracy have became interconnected, and since then have settled for the DNA of the post-communist era in proclaiming that there is just one way the economy and state work efficiently. Alternative voices have always existed however. This was also the conclusion of the Commission of Experts of the President of the United Nations General Assembly on Reforms of the International Monetary and Financial System in their final report of September 2009, also known as the Stiglitz-committee. They stated for example that ‘our global economy is but one of many possible economies, and, unlike the laws of physics, we have a political choice to determine when, where, and to what degree the so-called laws of economic behaviour should be allowed to hold sway.’ However in the euro crisis, there seems to be no place for any alternative approaches. The former Finance Minister of Greece Yanis Varoufakis has shared his experiences regarding the negotiations with his counterparts in the Eurogroup by saying: ‘One of the great ironies of the Eurogroup is that there is no macroeconomic discussion. It’s all rules-based, as if the rules are God-given and as if the rules can go against the rules of macroeconomics. I insisted on talking macroeconomics.’ In order to examine how these rules were constructed and how they could dominate the whole European integration process, we have to journey back into time. The making of the single market and the European institutes was a clash between three schools of economic thought, each of them still in a way dominant in the three main European economies: interventionists in France; laissez-faires in the United Kingdom and; social markets in Germany. As sociologist Francois Denord and journalists Rachel Knaebel and Pierre Rimbert explained in their article in Le Monde Diplomatique, the German social market system, also known as ‘ordoliberalism’, that was the central force of German post-war political economy from the 1950s forward became dominant in the EU’s economic policy, and the interventionist economic view on economic development then faded away. Ordoliberalism emerged in Germany in the interwar period but it became particularly popular in the post-World War II era in the works of Walter Eucken and Franz Böhm. It implies that the state should not distort the workings of the market as it is different from laissez-faire tactics because it also is characterised with the belief that free competition does not develop spontaneously. Compared with the laissez-faire approach, ordoliberalism offers a more unambiguous and less conflicted embrace of the role of the state in giving order to a market economy. The economy should be governed with an ‘economic constitution’ ensuring that states’ actions are constrained to take the form of general rules, an ordnungspolitik or ordering policy. Such policy was intended to limit the scope of action available to democratic governments, ruling out exceptions for particular situations, industries or professions. ‘Politicians can do what they like, as long as they follow the rules (which are effectively excluded from democratic discussion),’ as Denord, Knaebel and Rimbert wrote. As economist David Woodruff describes, ‘Ordoliberal theory had to compromise with a corporatist praxis it could not fully encompass nor defeat, a compromise encapsulated by “social market economy” formula.’ Over the 1980s, the set of rules in social market economy, which also had its influence in the political economy in for example the Netherlands and Austria, adopted neoliberalist free-market theories and from the 1990s adopted its financial component of deregulated financial markets, which were propagated already in the US and UK. There was political consensus to limit the role of the state even further, and in particular give space to the emerging financial sector to increase its role on economic development. This is what Wolfgang Streeck, Emeritus Director at the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies in Cologne, calls ‘consolidation state’. The growth of public debt was transferred in the 1990s into private debt and combined with the rule of low taxation this meant cuts in welfare states. The state has transformed itself from a ‘tax state’ into a ‘debt state’ and had to follow the logics of the markets, and especially the financial markets. If they don’t follow its rules, the state could be punished with higher interest rates on their sovereign bonds for example. Northern European member states, and in particular West Germany’s negotiating approach to the European Monetary Union, also resulted in the rule-based character of the resulting Maastricht Treaty of 1993 that set the tone on which the European institutions were constructed. The treaty was defended against the claim that by denuding voters of sovereignty, it violated democratic principles by arguing in the spirit of ordoliberalism that democratic governments were not well-suited to some aspects of economic management. The German Constitutional Court (Bundesverfassungsgericht) for example argued that the provisions of the treaty were sufficiently well-specified to grant European institutions determinate authority, any exceeding of which would require treaty modification and thus a new democratic imprimatur. Strictly rule-bound behaviour runs the risk of producing perverse consequences in an individual case for which the rules are poorly suited. European policymakers acknowledged this, but they also argue that ‘the consistent operation of properly chosen rules will have beneficial consequences that outweigh any undesirable outcomes arising from the application of rules to a particular case’, as David Woodruff writes in Governing by Panic: The Politics of the Eurozone Crisis. In a political economy context, such reasoning countered in the discussion the idea of soft budget constraints and moral hazard of austerity measures. The assumed beneficial consequences of rule-bound action to keep inflation and deficits low and the assumed long term benefit of not weakening the rules-based structures are asserted and the possible situational advantages of policy change (for instance, preserving long-term investments) are not discussed. ‘Flexibility was possible’, though it was ‘a political choice’ to opt for austerity and labour market reforms to cut wages according to Woodruff. For example, one alternative could have been to focus on the benefits of stimulating demand for exports rather than on the costs of bailouts of sovereign state debts for creditor countries like Germany, the Netherlands and Finland. The result is that even countries like the Netherlands and Germany with a tradition of searching for a political consensus in their own decision-making could put aside this tradition on the European level with their hard line approach to debt-ridden economies in Southern Europe. This is according to historian and political writer Timothy Garton Ash, which is only possible because the belief in the current economic strategy has been embraced by too many political fractions. ‘To achieve more consensus abroad [with other European countries], perhaps Europe’s leading power needs less consensus at home,’ Ash writes. Instead of being open about the failures of the economic and monetary building blocks and working to solve the problems as a genuine union, including by changing policies, European finance ministers and governments have started pointing the finger at each other. There are many different scapegoats – from reckless bankers to corrupt politicians – and their victims are not just Greeks or Spaniards, but the numerous impoverished people throughout the whole Eurozone. Anyone who looks at the bigger picture of how the European Union developed into a single market with a single currency will see that what Europe needs most is an honest debate about how interdependent European countries with a single currency are. The future of Europe must be based on renewed unity and solidary, but by taking into account the different kind of economies and cultures that exist. Such a new solidarity is only possible with a clear strategy to bridge the divisions and restructure the economies in Europe on a time-path that is set for individual countries. And such alternative strategies cannot be based purely on technocratic rules overruling democratic decisions. ‘We face a delicate balance,’ says economist Charles Wyplosz. ‘Institutions must bind the policymakers without violating the democratic requirement that elected officials have the power to decide on budgets. This argues against assigning wide discretionary powers to fiscal institutions but it is fully compatible with giving them either the authority to apply legal rules or to act as official watchdogs.’ Read more - Power shift from France to Germany

The ideal of economic supremacy

Background article

All Dutch consumers will benefit

Trade union guidelines

The ideal of European political union

About the Stability and Growth Pact

A European political union: back on the agenda

Reality check – violating the rules

Background article

Read more - Support for Lapavitsas

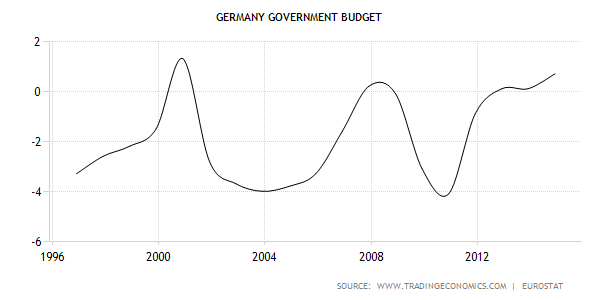

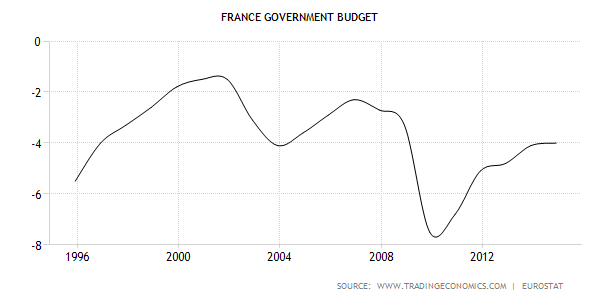

Graphs - German and French budget deficit

Background article

Reality check – accelerator of mistrust and anti-solidarity

What does default risk-free mean?

Cognitive capturing of the recovery programme

Long term decline of welfare state

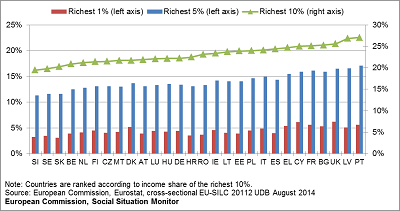

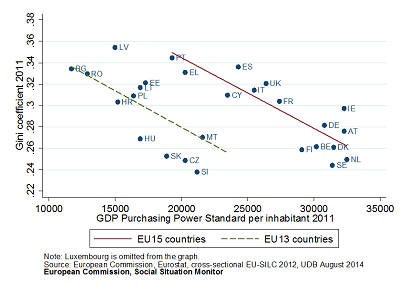

Reality check – rising inequality

Rising inequality

Read more - The Broker dossiers on Employment and Middle Class

Quote by Joaquin Almunia

What experts said about labour policies, employability and social control over employment

Data - Rising unemployment

A divided Eurozone, but with a single currency

Why policymakers keep saying there is no alternative

Footnotes