Global value chains offer many opportunities for rural entrepreneurs in developing countries to become competitive actors in world markets. But unless local power relations are taken into account, value chain development is unlikely to reduce poverty.

Proponents of globalization have long argued that free trade will lead to economic growth and improvements in the livelihoods of all, including the poor in developing countries. However, since it is evident that gains from globalization are not distributed equally, NGOs and policy makers are promoting the development of global value chains that include small farmers and entrepreneurs, as a way to lift millions out of poverty. But are they taking into account all the factors that determine who benefits and who remains excluded from value chains?

Global value chain (GVC) analysis is an analytical tool used in a variety of research fields. In the literature, a distinction can be made between studies of two buyer-driven chains: labour-intensive manufacturing and agro-commodity chains. Apart from focusing on different sectors, these areas of study diverge in the attention they pay to power relations within a chain. Research on labour-intensive manufacturing tends to be more neutral, seldom going beyond ‘observing’ differences in power. Studies of agro-based commodities tend to be more normative, reflecting the initial thinking on global commodity chains, which has its roots in dependency theory. Recent debates, however, are moving beyond this distinction, with the aim of developing a common framework that includes services as a third area of study. Although still GVC analysis in its infancy, crossing borders within and beyond the value chain literature is the trend, especially in attempts to understand the impacts of value chains on poverty reduction (see box).

This article focuses on weaker actors in agricultural chains – rural entrepreneurs involved in primary production, trading and small-scale processing – and how they can upgrade their operations and strengthen their economic power within global value chains.

Since the late 1990s, researchers have used GVC analysis to describe various agricultural commodity chains, including cocoa, coffee, cotton and tobacco. Development agencies and policy makers have also adopted GVC analysis to assist them in drafting agricultural development strategies. Such research has provided insights into opportunities for the poor to benefit from globalization. But the findings of some recent GVC analyses are alarming. Tilman Altenburg of the German Development Institute in Bonn, for example, believes that ‘value chains become more exclusive as small-scale producers fail to meet [the] rising scale and standard requirements’ imposed by those who control the chains.

Many researchers concerned with the exclusion of small entrepreneurs agree. In the cocoa sector, for instance, it is expected that in the future only a few more innovative and larger farmers will be able to continue producing cocoa for the world market. Smaller, non-competitive producers will be forced to look for alternative sources of income. This trend is reinforcing inequalities and goes against the grain of pro-poor development. To counteract this, and to ensure that rural entrepreneurs can grasp opportunities for upgrading, insights are required into the distribution of power, both within the value chain and locally.

Chain governance

The issue of the governance of value chains is crucial. Authority and power relations among buyers, processors and producers determine how incomes and other benefits are distributed, as well as the conditions under which small producers are included in the global division of labour. In other words, these power relations determine whether value chains will have an impact in terms of poverty reduction.

Value chains are not closed systems, but are part of larger institutional frameworks. They receive external inputs in the form of knowledge (from technical research institutes, extension services) and they are influenced by advocacy groups (trade unions, NGOs) focusing on environmental or social concerns, and by the policy priorities of national governments or international bodies such as the World Trade Organization, World Bank and UN agencies. They are also affected by social structures such as the level of organization of producers, or traditional hierarchical relations. These institutional frameworks are important because they either provide effective channels through which value chains can be strengthened, or ‘upgraded’, or they create barriers that can effectively block exchanges between actors in the chain.

Concentrating power

Agricultural value chains are increasingly driven by multinational traders and food processors. They, and to a lesser extent food product manufacturers, now determine production quality standards, and have the final say in linking producers to markets. One factor that has contributed to this concentration of power is that multinational traders and processors, as well as manufacturers and retailers, have streamlined their worldwide operations. Through takeovers and mergers, the multinationals have gradually increased the scale of their operations, and in the process have gained considerable economic and even political power.

But with increasing scale comes risk. The introduction of market reforms in many producing countries meant that the multinational buyers of primary commodities were vulnerable to the poor performance of their suppliers, and thus became more insistent on controlling product and process quality specifications further down the value chain. This is also due to the fact that as a result of structural adjustment programmes, national quality management systems have been abandoned and supplier failure has become more common. Faced with increasingly competitive global markets, firms have responded by attempting to cut costs and increase efficiency in the chain by outsourcing activities to lower-cost regions.

At the same time, companies are facing increasing competition for natural resources. Decades of overexploitation, combined with high rates of growth in emerging economies such as China and India, have made it more difficult to source raw materials such as tropical hardwoods, spices, minerals, agricultural commodities and fish. As the prices of these and other resources such as food crops and fuel fluctuate, companies constantly need to look for new sources of supply and to invest in the development of new value chains, as means to diversify their risk. Another strategy that multinationals can use to maintain control of their supply chains is to invest greater effort in building better relations with existing suppliers.

Consumer demands

Further factors that have led to multinational traders and processors controlling value chains include changing consumer preferences and demands, and the growing influence of retailers and supermarkets. Supermarkets in Europe can now insist, for instance, that tropical fruits such as mangos flown in from farms in Mali or Brazil are available all year round and that they are in top condition. Growing numbers of consumers want to know, for example, exactly where their coffee comes from, all the way back to a farm in, say, Costa Rica. Some consumers prefer to buy organic products, such as t-shirts made of organic cotton, while others want to be sure that child labour was not used to produce the products they buy. This so-called ‘traceability’ is a quality management tool and is increasingly used as marketing strategy for niche products.

Consumer satisfaction has become a common goal – and concern – of all actors in many supply chains. Firms are under pressure to ensure that not only their own companies but also producers and suppliers throughout the entire chain comply with internationally agreed labour and environmental standards and industry codes of conduct. As a result, international traders and food processors have become more dependent on the local suppliers operating at the bottom of a chain. This also entails greater responsibility, in particular to provide producers with the information and the new technologies they need to comply with new production and process standards. Because such standards usually do not (yet) apply to local domestic markets, and/or require substantial investments, producers need financial and other support to improve their operations.

Upgrading

If small producers in developing countries are to cope with the challenges of globalization and increased competition, it is essential that they improve or upgrade their businesses. This may involve acquiring new capabilities that enable them to participate in particular chains or clusters, or to access new market segments, and in the process gradually move up the value chain. There are various options for upgrading:

- product upgrading: moving into more sophisticated product lines with increased product value;

- process upgrading: transforming inputs into outputs more efficiently by reorganizing the production system or introducing superior technologies;

- functional upgrading: acquiring new, superior functions in the chain, such as design or marketing, or abandoning existing low-added value functions to focus on higher value added activities; or

- inter-sectoral upgrading: applying newly acquired competences to move into a new sector.

The concept of upgrading reflects a shift away from the idea that state-driven interventions are needed to build up capital and boost technological innovation, to one in which upgrading is the outcome of organizational learning and inter-firm networking. This concept has now been applied in various fields, from cluster studies to the value chain approach.

All of these options require improved access to information and knowledge.

Here too, power relations play a part in determining what opportunities for upgrading are available, and to whom. For weaker actors within a chain, upgrading does not happen automatically, but can be enabled or hindered by more powerful players, including governments, and by existing social structures. For example, research and extension services (which are often funded by governments out of taxes) can support cotton farmers in shifting from conventional to organic cotton, which fetches a price premium. But the size of this premium is negotiated between buyers and sellers, and can fluctuate from year to year, affecting the decisions of cotton farmers on whether to invest in improving their plantations.

The gains resulting from upgrading strategies are often unequally distributed. For example, fair trade organizations aim to pay poor farmers a fair price for their produce, but membership of such schemes is often linked to land ownership. As a result, the benefits of fair trade often go to male landowners, and not to the migrant labourers and female farmers who do not have title to the land they work. Many development initiatives have attempted to benefit small producers by shortening or reconfiguring value chains. In practice, this results in the exclusion of middlemen, who may also be poor and may have difficulty finding alternative employment. Experience has shown that farmers’ organizations often fail to take on the role of these middlemen themselves. Few interventions have focused on making trading networks more efficient.

Thus the weakest actors in a chain often enjoy very few opportunities to upgrade their businesses. Ultimately, they may be excluded from the chain altogether and be forced to search for alternative ways of generating an income. However, as Malcolm Harper shows (in his article: Beyond the retail revolution), given the right circumstances, small producers can be profitably included in value chains.

Empowerment

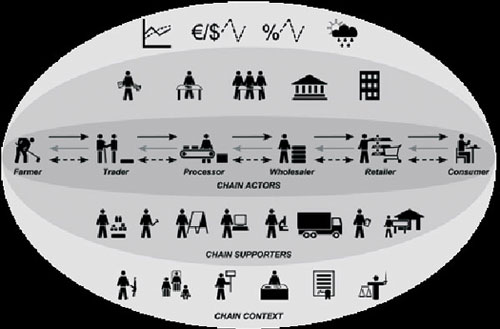

From farm to fork: the numerous factors that influence global value chains.

KIT/IIRR (forthcoming) Value Chain Finance: Beyond Microfinance for Rural

Entrepreneurs.

In order to be profitably included in value chains, farmers and small producers need to be empowered to make their own informed decisions about their work and livelihoods. In fact, empowerment can lead to ‘self-exclusion’, if farmers choose to remain outside or leave a chain because they foresee too little profit and too many risks.

Chain empowerment means that farmers strengthen their capacity to manage parts of a chain or specific activities. In this, two aspects are important: who does what in the chain (vertical integration), and who determines how things are done (horizontal integration). Farmers may be concerned only with production: they prepare the land, plant seeds, apply fertilizer, control pests and weeds, and harvest the crop when it is mature. But they may also be involved in activities higher up in a chain, including sorting and grading, processing or trading their produce. If farmers are involved in a wide range of activities, including production, this contributes to their empowerment. But true chain empowerment requires that these producers gain economic power by becoming involved in managing the chain. Farmers can participate in various aspects of management, such as controlling the terms of payment, defining grades and standards, or managing innovation. One way they can obtain the power to do this is to set up their own organizations.

Farmer organizations

Governments, donors and researchers are increasingly recognizing the vital role that producer organizations can play in empowering the poor. In the past these organizations, mainly in the form of cooperatives, were based on ideology or the principle of solidarity and were intended to ensure benefits for all their members. In their efforts to empower the poor, donors today are promoting farmer organizations as a means of giving poor farmers more economic power, and thus to play a more entrepreneurial role. But in order to play this role well, farmer organizations require new capacities, and thus investments. There is also a potential tension between professionalization of the management of these organizations and the influence of their members. In their contribution to this special report, Roldan Muradian and Ellen Mangnus focus on the issue of entrepreneurship in farmer cooperatives and the challenges involved.

Inclusion with and for the poor

Including the poor in value chains is not just a matter of involving them in farmer organizations. It also requires their empowerment through improved competences, resources and technology. Any GVC analysis should start from the recognition that relations in a value chain are determined not only by shared goals and interests, but just as much by power and diverging interests. Moreover, the inequalities that exist in a society – endorsed by social and political structures at local and global levels – largely determine who will benefit and who will remain excluded from value chain development.

Women workers and rural entrepreneurs are perhaps the most familiar victims, as Linda Mayoux points out (in her article: ‘Engendering benefits for all‘). The potential of interventions to strengthen or upgrade value chains and to empower small farmers in developing countries will remain limited as long as poor women and men cannot negotiate the conditions under which they want to participate in a chain. As long as they are unable to do this, being included in a global value chain can be a rather risky business, rather than an opportunity for growth.

The author wishes to thank Bart de Steenhuijsen Piters (Royal Tropical Institute, Amsterdam) and Peter Knorringa and Bert Helmsing (Institute of Social Studies, The Hague) for their comments on earlier drafts of this article.

Footnotes

- Global value chain (GVC) analysis has its roots in world systems theory and dependency theory, and is part of the wider interdisciplinary research on value chains. The GVC approach, initially referred to as ‘global commodity chain analysis’, was introduced by Hopkins and Wallerstein (1986, 1994), who discussed a variety of chains for agricultural products.

Hopkins, T.K. and and Wallerstein, I. (1986) Commodity chains in the world economy prior to 1800. Review 10(1): 157–170.

Hopkins, T.K. and and Wallerstein, I. (1994) Commodity chains: Construct and research, in G. Gereffi, G. and Korzeniewicz, M. (eds) (1994) Commodity Chains and Global Capitalism, Praeger. - Humphrey, J. and Schmitz, H. (2000) Governance and Upgrading: Linking Industrial Cluster and Global Value Chain Research, IDS Working Paper 120.

Kaplinsky, R. (2004) Competitions Policy and the Global Coffee and Cocoa Value Chains, Institute of Development Studies University of Sussex, and Centre for Research in Innovation Management, University of Brighton.

Knorringa, P. and Jorg Meyer-Stamer, J. (2008) Local development, global value chains and latecomer development, in: J. Haar and J. Meyer-Stamer (eds) Small Firms, Global Markets: Competitive Challenges in the New Economy, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp.18-37. - Daviron, B. and Ponte, S. (2005) The Coffee Paradox: Global Markets, Commodity Trade and the Elusive Promise of Development. London: Zed Books.

Gibbon, P. (2000) Upgrading primary production: A global commodity chain approach. World Development 29 (2): 345-63.

Ponte, S. (2002) The ‘latte revolution’? Regulation, markets and consumption in the global coffee chain. World Development 30 (7): 1099-1122. - Bair, J. (2008) Analysing global economic organization: embedded networks and global chains compared. Economy and Society 37(3): 339-364.

- Daviron, B. and Ponte, S. (2005) The Coffee Paradox: Global Markets, Commodity Trade and the Elusive Promise of Development. London: Zed Books, p.29.

- See, for example, Gibbon, P. (2000) Upgrading primary production: A global commodity chain approach. World Development 29 (2): 345-63.

Fold, N. (2002) Lead firms and competition in ‘bi-polar’ commodity chains: Grinders and branders in the global cocoa-chocolate industry. Journal of Agrarian Change 2(2): 228-47.

Gibbon and Ponte (2005).

Kaplinsky, R. (2004) Competitions Policy and the Global Coffee and Cocoa Value Chains, Institute of Development Studies University of Sussex, and Centre for Research in Innovation Management, University of Brighton.

Ponte, S. (2002) The ‘latte revolution’? Regulation, markets and consumption in the global coffee chain. World Development 30 (7): 1099-1122.

Daviron, B. and Ponte, S. (2005) The Coffee Paradox: Global Markets, Commodity Trade and the Elusive Promise of Development. London: Zed Books. - Cf. Larsen, M.N. (2003) Quality Standard Setting in the Global Cotton Chain and Cotton Sector Reform in Sub-Saharan Africa. DIIS Working Paper 03.07. Copenhagen: Danish Institute for International Studies)

- Cf. Vargas, M.A. (2001) Forms of Governance, Learning Mechanisms and Upgrading Strategies in the Tobacco Cluster in Rio Parde Valley-Brazil. IDS Working Paper 125, Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex.

- The GVC approach has been adopted by a number of Dutch development organizations and knowledge institutes, such as the Royal Tropical Institute, ICCO, Hivos and SNV, and international institutes such as FAO, USAID and IFAD.

- Altenburg, T. (2006) Governance patterns in value chains and their development impact, European Journal of Development Research 18(4): 498–521.

- A number of authors observed this trend for the global cocoa chain (cf. Kaplinsky, 2004; Gibbon and Ponte, 2005; personal communication Vigneri, 2007).

- Saurabh Mehra, WCF West Africa Committee and Stephan Weise, Program Manager, IITA/STCP stated this during their presentation on their West Africa Strategy during the WCF Partnership Meeting Amsterdam, 23 May 2007.

- Gereffi, G. (1994) The organization of buyer-driven global commodity chains: How US retailers shape overseas production networks, in G. Gereffi and M. Korzeniewicz (eds) Commodity Chains and Global Capitalism. Praeger; Gibbon (2001).

- In discussions of chain governance, generally a distinction is made between two types of chains where the producers have different positions. Producer-driven chains are found in capital- and technology-intensive sectors. Multinationals are the central players in such chains, which are complex and multilayered, often marked by international subcontracting of the more labour-intensive parts of the process (such as the computer and automobile industries). In contrast, buyer-driven chains are found in more labour-intensive sectors (e.g. garments and footwear), where design and marketing are centrally controlled and in agro-commodities (e.g. tropical crops such as cocoa and coffee). In buyer-driven chains the so-called ‘lead firms’ – large retailers, branded marketers and branded manufacturers – act as strategic brokers who link producers and markets; their privileged knowledge of strategic research, marketing and financial services grants them this position. Agricultural value chains are increasingly driven by international traders and processors. Both chains are seen as vertical networks. Although the distinction between producer- and buyer-driven chains is helpful, there have been attempts to refine the concept of governance, focusing on inter-firm relationships and institutional mechanisms through which non-market of activities in the chain are coordinated. See Gereffi, G., J. Humphrey and T. Sturgeon (2004) The governance of global value chains. Review of International Political Economy 12: 78–104.

In discussing the overall governance of a chain, the distinction between buyer- and producer-driven chains is still valid (Gibbon and Ponte, 2005). - Extension services provide farmers with information and advice on agricultural practices.

- Besides governance and the institutional frameworks of global value chains, Gereffi (1994) distinguished a third dimension: their input–output structure, or the sequence of interrelated value-adding activities (including product design and engineering, manufacturing, logistics, marketing and sales) and the geographical coverage, which refers to the spatial dispersion or concentration of activities within and across locations.

- Gibbon (2001) proposes a third type of governance: trader-driven governance.

- In West Africa, before the introduction of structural adjustment programmes (SAPs), cocoa production and marketing used to be under state control, and different countries had different marketing and pricing systems. The market liberalization, privatization and institutional reforms imposed by the World Bank led to reduced state involvement in cocoa marketing and other services, and the opening up of markets to competition. As a result, global traders took over tasks that used to be the responsibility of the state. See Akiyama, T. Baffes, J., Larson, D. and Varangis, P. (2001) Market reforms: Lessons from country and commodity experiences, in Akyiama et al. (eds) Commodity Market Reforms: Lessons of Two Decades, World Bank, pp.5-35.

- See Ellen Lammers (2007) The regulation gap, The Broker 3; Evert-jan Quak (2008) A delicate business, The Broker 8.

- Keesing and Lall (2002), in J. Humphrey and H. Schmitz (eds) Developing Country Firms in the World Economy: Governance and Upgrading in Global Value Chains. INEF Report 61/2002. INEF-University of Duisberg, Germany.

- Humphrey, J. (2003) Upgrading in Global Value Chains. Background paper for the World Commission on the Social Dimensions of Globalization. Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex, UK.

- Gibbon, P. and Ponte, S. (2005) Trading Down: Africa, Value Chains, and the Global Economy, pp.87–8.

- This is one of several proposed typologies, but it has been criticized. See Gereffi (1999); Humphrey, J. and H. Schmitz (2002) How does insertion in global value chains affect upgrading in industrial clusters? Regional Studies 36: 1017-28.

- Humphrey and Schmitz (2000); Gereffi, G. (1999) International trade and industrial upgrading in the apparel commodity chain. Journal of International Economics 48(1): 37-70;

Schmitz, H. (1999) Global competition and local cooperation: Success and failures in the Sinos Valley, Brazil. World Development 27(9); 1627-50; Vargas (2001). Some studies have shown how, in the process of upgrading, knowledge and information flow from the lead firms in each chain to their suppliers or buyers: Gibbon and Ponte (2005) Trading Down: Africa, Value Chains, and the Global Economy, p.89; Gereffi (1999). - Peppelenbos, L. and Mundy, P. (eds) (2008) Trading Up: Building Cooperation between Farmers and Traders in Africa. Royal Tropical Institute, Amsterdam, and International Institute of Rural Reconstruction, Nairobi. View PDF

- KIT, Faida MaLi and IIRR (2006) Chain Empowerment: Supporting African Farmers to Develop Markets. Royal Tropical Institute, Amsterdam; Faida Market Link, Arusha; and International Institute of Rural Reconstruction, Nairobi. View PDF