This is one background article (of originally 4) in the context of the online debate about Dutch development cooperation triggered by the report Less Pretension, More Ambition by the Dutch Scientific Council for Government Policy (WRR). In this background article the following questions are intended as a context for formulating strategies towards global development and introducing issues for further discussion:

- What are the motives for providing aid? Should collective self-interest be the driving force, or should we also include moral motives, to safeguard the interests of the weakest?

- How do we perceive and define development? Should it be defined as modernization, as economic growth, or should we use a multidimensional definition of poverty, one that covers material poverty, (human) security, and social, economic, cultural and political participation?

- How should we look at development policies: is a more technical and interventionist top-down approach desirable, or should development policy focus on catalysing endogenous development processes by removing obstacles and enhancing an enabling environment?

- What scale should we use as a starting point for analysis and policy making? Should it be the state, the individual in his or her social environment or the regional and global level? If all of the above, how do we prioritize and consolidate them?

The energetic online debate about the motives, definitions and perceptions of development so far is a starting point for reformulating development policies.

The WRR report focuses a great deal of attention on the motives, goals and principles underlying development policy. And rightly so, because any policy theory has to start with a clear description of its policy goal, addressing why that goal needs to be achieved, for whom and on whose behalf. These fundamental questions will largely determine the ultimate ins and outs of a policy, the ‘what’ and the ‘how’.

Motives

The WRR distinguishes between two types of motive for aid that can, in principle, co-exist: moral motives and self-interest. Each of these motives implies a different interpretation of what aid should do or look like.

A number of contributors to the WRR blog state that both moral motives and self-interest play a role in today’s aid industry. However, the WRR’s recommendation that collective self-interest should prevail over moral motives has provoked criticism from various quarters.

Henk Jochemsen (19/1/10 en 26/3/10), for example, suggests that normative choices are needed, while Allert van den Ham believes it is essential to support the weakest, which means promoting democratization and emancipation. Eric Smaling opposes the idea that there ‘first has to be growth before anything can be shared. It’s one of the choices available, but one that abandons solidarity, and that’s something I feel very strongly about’.

There is a certain degree of confusion in the debate about the motives, development perceptions and goals of giving aid. At a deeper level, however, it does seem there is consensus on the need for a more structural approach. What the WRR presents as modern moral trends (the capabilities and rights approaches, and alternative globalism) are described by others as alternative development visions or goals.

The WRR describes the current goal of development policy – poverty reduction – in fairly negative terms, namely as ‘care for the poor’ and providing services to alleviate distress. In the WRR’s view, a more structural approach is needed that promotes self-reliance and ‘opportunities for development and economic growth’, so that countries can take into their own hands the task of helping the poor.

Many contributors express considerable resistance to the WRR’s narrow definition of modern poverty reduction and the related portrayal of Dutch development policy as subsidizing ‘palliative’ measures that scarcely contribute to productivity. Some argue that current development policy applies a much broader definition of poverty than the WRR suggests. As Paul Hoebink notes, ‘the WRR seems to have overlooked the fact … that nowadays a broad, “multidimensional” definition of poverty is being embraced’.

Maarten Brouwer (Dutch) writes that donors and developing countries had already agreed in 1999 ‘on an interpretation of the term poverty reduction, based on five different dimensions: social, economic, cultural, political and security-related. All these dimensions of poverty relate to the degree to which individuals are free to develop in that dimension. If all these dimensions are taken at face value, what more is then needed to promote self-reliance?

Economic focus

Another, related criticism concerns the goals of development, and in particular the WRR’s one-sided focus on increasing productivity for the sake of economic growth. At first reading, the report indeed seems to be set on counteracting what it sees as the donors’ excessive emphasis on the social sectors. But the WRR also says that it helps to ‘reason in terms of an economic sector, a political system, a government apparatus and social fabric, although these four elements can only be differentiated from each other to a limited degree’. In other words, the WRR does acknowledge that the economic component must be part of a broad, integrated approach.

If the WRR is only seeking to re-establish the balance and the relative weight of economic productivity within the dynamics of a broader social, political, economic and governance framework, then something approaching a broad consensus would appear to be possible.

Opinions do differ, however, as to whether this is already happening in practice.

Interventionism or social change

A parallel discussion on the blog concerns the desired approach to aid. Do we need a more technical or interventionist approach to aid? Or do we need an approach that views development as a complex series of social processes of change, in which top-down intervention makes less sense? Many contributors criticize the WRR for adhering to this more interventionist stance.

Laurent Umans writes that the ‘report mobilizes a classic image of donors and recipients’. Francine Mestrum emphasizes the endogenous nature of development and advocates more ‘focus on what poor countries can do themselves’. She adds that ‘the first condition for a successful development policy clearly has to be a national development programme. Expertise has to come from within. It is not in Western countries that one can decide what good development is and what it is not.’ She elaborates 18/2/10.

Rob D. van den Berg points out that the report largely ignores the debate on ‘catalysing development’ that took place at the beginning of this century. ‘Many experts argued that aid should in fact have a catalytic role, providing a spark that would initiate home-grown developments, rather than be directly responsible for economic growth and poverty reduction.’

Even if the WRR doesn’t refer to this debate explicitly, its ultimate goal seems to be the same. For Seth Kaplan, ‘the one key element that sho

uld drive all change is that aid should work towards making “countries and peoples self-sufficient”. This ties together many of the report’s recommendations’. He advocates capacity building and suggests that the ‘best way to do this is to focus on key “nodes” that promise to have multiplier effects across institutions’. These nodes are similar to Van den Berg’s catalysts, or the drivers of change referred to by the WRR. Or, in the words of Tom van der Lee, ‘Development (or modernization) is a political process, a struggle for emancipation, much more than a mechanical solution for a technical problem … This fits in with the WRR’s very recognizable recommendation that aid must, above all, contribute to self-reliance. We interpret this not only in an economic, but also in a political and social sense, because we base our thinking on a broad concept of prosperity.’

If there is indeed such a consensus, the important thing now is to broaden the debate about how to develop the diagnostics so that the strategic catalyst role can be used as effectively as possible.

Scale

Scale is another fundamental issue. Is the state the basic unit of analysis and policy making, or should other dimensions also be considered as a starting point? If so, should policy making be on a global scale or a human, individual scale? Should it be implemented on a micro or a macro level? Or a combination of the two, depending on the context? Louk Box writes, ‘As a government advisory council, the WRR is rather donor- and state-centred’.

And Louis Emmerij writes, ‘of course you need a macro framework, and increasingly a global framework, within which you can flesh out national and regional policy details in a consistent manner’.

A final aspect of scale that underlies much of the debate is the question of whether countries or indeed people (and their social ties) should be taken as the point of departure for policy. Jan Gruiters believes that ‘recognizing that the state perspective is insufficient and needs to be supplemented by the human perspective is not only important for reasons of security, but equally so for development’.

For some contributors, development should not focus on the progress of countries but of individuals – human development, in other words, or human security. Leon Willems believes that ‘a secure and dignified life for all people’ should be the central aim of a development policy. Anneke Wensing comments that overall the WRR report is ‘shockingly gender blind’. Further, in her ‘opinion, the WRR report ‘ignored the role of people – both men and women – in the development process, even though economic growth and development are created by people, by men and women, each of whom contributes in their own way to development and therefore creates the conditions for development to take place in’.

Modernization

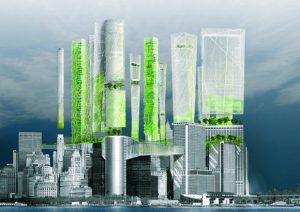

The pictures in this article are images of winning designs of the 2010 Skyscraper Competition organized by eVolo Magazine (www.evolo.us). This annual event recognizes ‘out of the box’ ideas that redefine skyscraper design.

Lastly, opinions are divided on the WRR’s definition of development ‘as a conscious acceleration of the process of modernization’. First and foremost, there is criticism of the use of the term ‘modernization’, which the critics see as a fundamentally Western concept.

More fundamental criticism of the WRR’s definition of modernization, which has major potential consequences for further policy interpretation, relates again to the scale at which the issues in question are addressed.

Anyone who takes the Earth as a basic unit of analysis (and policy) and not the nation state, may end up with entirely different priorities. Rene Grotenhuis remarks that ‘modernity as a development project of the Western world (Europe, North America, Japan) is reaching its ecological and economic limits. It is clear that the linear extension of that modernity is not feasible. We therefore need two things that can both be characterized as development: a thorough reform of the Western model in the direction of sustainability (social and ecological) and the involvement of developing countries in sustainable globalization’.

In a second contribution, Grotenhuis proposes defining an ‘overarching goal’ that links together the WRR’s three goals. ‘Poverty reduction, economic growth and contribution to global public goods are not convincing as goals. They could also be seen as intervention strategies, actions taken to realize something on a higher level’. In other words, they essentially can be seen as instruments, resources for achieving a different goal. As far as Grotenhuis is concerned, that overarching goal is sustainable global development.

Continue reading: all four sections of the Special report in issue 19 of The Broker Magazine (april 2010)

- Getting the basics right – General principles for a new development policy

- Going global – Alternative political projects

- Identifying obstacles – Strategic choices through context analyisis

- Building a new structure – Institutional architecture for global development