A growing number of people in the industrialized world work under insecure employment conditions. This is due to increasing labour market flexibility, which has influenced the nature of employment and the related power relations. This fundamental change has consequences for labour conditions, social policies and the quality of work.

In the United States, it is no exception to find people working three jobs for more than 40 hours a week who do not manage to earn a living wage. This is increasingly happening in Europe as well. This category of workers is known as the ‘working poor,’ a workforce that is unable to make ends meet even though they have paying jobs. In the US there are four times as many people in working poor households as there are in poor households where none of its members are employed. 1 And, in the United Kingdom, over half of the 13 million people living in poverty are from working families. 2

The number of working poor is decreasing in the developing world, in line with the reduction of extreme poverty (see figure 1). In contrast, the number of working poor is on the rise in the United States, and especially in crisis-hit Europe. Although the figures in industrialized countries remain well below the global average. According to the 2010 Eurostat figures, 8.2% of workers in the Eurozone countries earned less than the region’s average poverty rate of €10,240 euros a year for a single adult worker, which is up from 7.3% in 2006. The numbers are nearly double in Spain and Greece. In addition, the US Labour Department estimated that 7% of single adult workers in the United States were living below the poverty threshold of $10,830 (or approximately €7,873) in 2009, whereas the figure was 5.1% in 2006. 3

Figure 1. Working poor at global level, in absolute numbers and in percentage of total employment. Source: International Labour Organization (2014) Global Employment Trends. ILO, p. 111.

However, governments, especially in crisis-hit Europe, continue to perceive ‘employment activation’ as the best route out of poverty. 4 The European Commission for example argues that “the path of economic growth of a country is critically affected by the size, utilization and quality of its workforce.” 5 Public authorities have accordingly changed social policies and adjusted welfare benefits to ‘activate’ the working population. In many cases they have adopted a strategy often referred to as ‘flexibilization’, where a job market is supported that is responsive to market dynamics. 6

One of the reported trends of more labour flexibility however is its contribution to a growing class of working poor. 7 Critics, such as Arne Kalleberg and Katherine Stone, 8 argue that the quality of work and overall living standards can be negatively affected by the associated labour market reforms. 9 Supporters of a flexible labour market however emphasize its potential to spur labour mobility, counter unemployment trends and strengthen market efficiency. The IMF for example sees flexibility as an answer to rigid labour market institutions that obstruct job creation and tend to be associated with higher levels of unemployment. 10

Changing dynamics

Since the 1980’s the European labour markets have become more flexible, which made the European situation more in line with North America. The UK government under Margaret Thatcher pioneered these reforms by weakening union power and strengthening employer power. As legislation reduced the power of trade unions, membership declined, wage councils were eliminated and employment protection was weakened. 11 While highly-regulated labour markets did fit well with relatively closed economies up to the 1970s, the intensity and range of competition since the onset of globalization has called for more adaptable production systems and labour markets. Flexibility is then, as neoclassical economists argue, an inherent precondition for employment creation and economic growth in this global economy. 12

The dynamics over the past three decades challenged the existing ‘standard employment relations’ (SER), as Leah Vosko, Professor in Feminist Political Economy at York University, describes it. The reliance on a traditional relationship between employer and employee, structured in a permanent and full-time contractual engagement, appeared to be no longer suitable to cope with the new pressures and demands of the global economy. These cover, for example, outsourcing of production processes across boundaries and competitive pricing due to growing international competition. This has led to a decline in the significance of full-time and permanent employment, towards an expansion of ‘non-standard’ flexible forms of employment, such as temporary and part-time work. 13

In practice, flexibilization refers to the externalization of labour, meaning companies hire an increasing share of their workforce outside of the corporation. While companies used to organize their workforces internally, now employers have created new types of employment relationships that allow them to adapt more easily to market-related fluctuations. These types range from hiring temporary workers, contracting part-time employees, or outsourcing activities to freelancers and the self-employed.

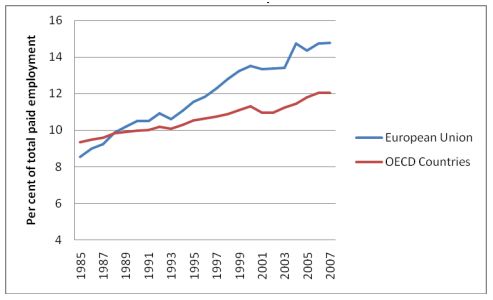

Figure 2. Growing prevalence of temporary work in OECD countries, 1987-2007. Source: OECD via International Labour Organization (2012) ‘From Precarious Work to Decent Work: Outcome Document to the Workers’ Symposium on Policies and Regulations to combat Precarious Employment.’ International Labour Office, Bureau for Workers’ Activities.

As we see in figure 2, temporary employment has increased steadily in OECD countries since the 1980s and constituted 12% of all employment in 2007. By only looking at figures up to 2007, we maintain an overview of the broad trends and not of the effects the subsequent economic crisis had. In the European Union the rise of temporary work increased with 115% as compared to 26% for overall employment. 14 The figures are even more pronounced for the youth in Europe, where part-time employment was 25% in 2011. Another 40.5% of employed youth in the region worked on temporary contracts. 15

Some argue that increased flexibility is advantageous for workers, who get more freedom to work on their own terms. Others argue that it eases access to a formerly closed labour market for groups who previously struggled to get jobs, such as women, migrants and disabled people. However, the ILO finds that such benefits do not reach all flex workers. Their 2012 report, ‘From precarious work to decent work’ shows that the quality of different forms of temporary contracts is actually lower than that of ‘regular’ permanent jobs. 16 For example, temporary engagements do not require employers to offer their workers job security or stability, fixed wages, or opportunities for skill development. 17

There has been a negative qualitative shift taking place in the labour market. It has generated new relations of employment characterized by poorer working conditions, wages, benefits and ‘new social risks’ of poverty and family instability. 18

The structural change in the character of the labour market thus implies not only a transformation of employment relationships, but also a shift of risks from the principal employer onto the employee. These new flexible arrangements signify a move towards work that is insecure, unpredictable and risky from the point of view of the worker, because of a lack of protection and associated social benefits. 19 The combination of the uncertainty of temporary employment and the absence of labour protection lowers the quality of work for these types of labour relations.

Even if flexibilization is argued to be good for job creation and growth, it has become more and more synonymous with lower pay, insecurity, and more regular unemployment. 20 A concept often associated with an increase in insecure employment conditions is ‘precarious work.’ In this perspective, some observe that the formal labour market is now divided between better-off workers protected by national regulatory frameworks and a legion of precarious workers with no job security, and a growing socioeconomic vulnerability for an underclass of women, immigrant workers and poorly-educated workers with temporary contracts. 21

Debating the future of employment

There is a growing body of scholarly approaches to the social and political implications of increased flexibilization, and its associated precariousness. The academic and political debate on the proliferation of this new type of employment is interpreted two ways. It is either interpreted as a widespread global issue, challenging the nature of work. Or it is understood from a more contextual perspective in which the issue of flexibilization and its perceived consequences have been over-generalized.

The American sociologist, Arne Kalleberg, perceives this form of ‘unpredictable work’ as a global challenge, with a wide range of consequences. He points out that the high level of insecurity for large numbers of people who are engaged in flexible work “has pervasive consequences not only for the nature of work, workplaces, and people’s work experiences, but also for many non-work related individual (e.g., stress, education), social (e.g., family, community), and political (e.g., stability, democratization) outcomes.” 22. The insecurity created by precarious work affects households and families, for instance by affecting couple’s decisions on important matters such as marriage and children. At the community level, precarious work may lead to a lack of social engagement, measured in declined membership in voluntary associations, in trust and in social capital. 23 As one of the first scholars to theorize about the ‘precariat,’ the late French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, considered it as a new mode of domination based on a generalized and permanent insecurity that make the workers accept their exploitation, or ‘flexploitation’ as he labels it. 24

The British economist Guy Standing goes a step further and defines a new social class, the precariat, or a ‘class-in-the-making’, which he contrasts to the ‘salariat’ in stable full-time employment. 25 Defining the precariat as a new class removes itself from the significance of the more traditional ‘SER-centred’ logic, 26 which centres on the traditional form of employment. 27 Standing argues in his book The Precariat, The New Dangerous Class (2011) that one of the potential political consequences of this loosely-tied social class is that its members might be more susceptible to mobilization by far-right forces as they lack the resources to organize independently.

Without questioning the increased precarious and insecure nature of work, Ronaldo Munck of Dublin City University, argues that the concept of precariat is questionable because there is no clear definition. He considers the idea of the precariat as a new concept as a Eurocentric phenomenon, and points out that precarity has long been the norm for workers in the developing world. Similarly, 28 Jan Breman criticized Standing for drawing his examples from advanced economies, despite his claims that the precariat is a global class. 29

Conversely, in her blog post for the London School of Economics and Political Science, Senior Lecturer in Labour Studies, Elizabeth Cotton, argues for avoiding construing the proliferation of precarious work as a global catastrophe. 30 Referring to the work of Kevin Doogan, Senior Lecturer in the Centre for Urban Studies at the University of Bristol, she questions the negative perception of present labour market transformations and argues that there is an over-generalization taking place.

In his book, New Capitalism? The Transformation of Work, Doogan namely argues that these misconceptions have resulted in a substantial gap between public perception and real labour market changes. 31 He sees a lack of distinction being made in different types of (temporary) employment arrangements, which according to Doogan creates over-generalizations of particular cases. Cotton describes this in her blog writing, “we haven’t all become precarious to the same degree at the same time.” Both scholars believe that misguided perceptions have influenced statistical data on labour market dynamics, and have tilted the discussions on flexibility and job security towards the negative. 32 Public perception would thus be misguided about the reality of the changes in the labour market and the wider economy.

Dealing with the new order

Different approaches have been suggested over time to find a balance between a competitive and dynamic labour market and continued job security and protection for workers. One such approach has been pushed by trade unions working globally, also described as Global Union Federations. These federations actively negotiate Global Framework Agreements (GFA) with transnational companies, which are based on voluntary compliance and enforcement.

In 2012, Volkswagen signed an agreement limiting temporary work at their plants and setting principles for use of temporary contracts in the entire Volkswagen Group worldwide. This particular GFA was encouraged by the global trade union, IndustriALL, and came as a response to a growing body of ‘precarious workers’ that were employed by Volkswagen as a “key flexibility tool.” 33 The work and growing relevance of IndustriALL is an example of contemporary responses to the global labour market.

As this example of the multinational Volkswagen shows, increased mobility of capital has challenged workers’ bargaining power and rights. 34 Because of a lack of a central workplace and social representation, marginalization and vulnerability is perpetuated for precarious workers. 35 Reportedly, since the 1970s, fewer workers have joined or continued their membership with trade unions, which according to the ILO is an indication that there is an increase in global insecurity and inequality. 36 Global unions such as IndustriALL have adopted one way of approaching the global movement of capital and labour. They attempt to negotiate rights across boundaries, of which the reach seems to have exceeded the ability of nations and regular labour movements to regulate. 37

The ILO finds that without workplace empowerment through trade unions and collective representation, legal provisions and regulations for this group of flex workers often do not materialize in practice. 38 Corporations that largely rely on subcontractors should take steps to decrease this flexibility rate and make no difference between employees and subcontracted workers. This can take place through negotiations with (global) trade unions but can also be encouraged by governments. However, as the UK think tank, the Policy Network finds that the traditional social-protection systems are often poorly equipped to negotiate the demands following the structural changes in labour markets. 39

A government-centred approach to manage the new flexible labour force is the Danish model of ‘flexicurity’, 40 which was introduced in Europe as a means to deal with the flexibility of the labour market, the welfare state and their interaction. In principle, the model aims to combine flexibility and security, and tries to reach economic growth without undermining social welfare. It follows, in part, from normative concerns with social exclusion and increased precariousness. Some scholars do however argue that the flexicurity model is too focused on flexibility and lacks any security, and that it would be more appropriate to label it ‘flexinsecurity’. 41

The European Council argues that “providing the right balance between flexibility and security will support the competitiveness of firms, increase quality and productivity at work, and help firms and workers to adapt to economic change.” 42 It sees flexicurity as a ’crucial element’ of the European Employment Strategy and as a means to modernize labour markets and contribute to the achievement of the 75% employment rate target set in the Europe 2020 Strategy. 43 At its introduction, it was promoted as a win-win solution that would further the interests of both workers and employers, and as a policy that would be based on compromise generated through social dialogue.

However, the concept of flexicurity is rather ambiguous, as it requires a range of possibilities and combinations of policies and thus lacks specification in its approach. The GUSTO study project, for example, finds flexicurity to be a concept that pleases everyone, including those with completely different views regarding labour market problems, solutions, and the translation of the political concept into practice. 44 Ton Wilthagen, Professor of Labour Market Studies at the Universiteit van Tilburg, argues that the political and social feasibility of labour market and work organization reform that takes into account both sides of the coin, such as flexicurity, depends on the extent to which parties’ interests are most prominently served. 45

A third approach to labour market dynamics, in line with GUSTO’s suggestions, is a more comprehensive approach. Leah Vosko describes it as the ‘beyond employment’ approach and notes that this concept, “pursues a vision of labour and social protection inclusive of all people, regardless of their labour force status, from birth to death, in periods of training, employment, self-employment and work outside the labour force, including voluntary work and unpaid caregiving” 46. Describing this approach as ‘the most promising’, she perceives the model as being able to spread social risks and de-link protection of workers from their employment status. Some practical implications mentioned are the concept of ‘universal basic income’ and government-led job guarantee programmes. 47 However, these alternative propositions have not taken hold to-date.

As we have seen, the growth of precarious work poses not only a challenge for workers but also for wider society. It creates “greater economic inequality, insecurity, and instability.” 48

As a response to the situation with less job security and a decrease in rights, the International Labour Organization (ILO) has coined the concept of decent work. The decent work agenda of ILO covers four areas: creating jobs, guaranteeing rights at work, extending social protection and promoting social dialogue. 49

In the ILO discussion paper, ‘Moving from Precarious Employment to Decent Work,’ John Evans, Secretary General of Trade Union Advisory Committee to the OECD and Euan Gibb, Researcher at the Service Employees International Union in Canada, put forward some bold recommendations. 50 National governments and international organizations, such as the IMF, the OECD and the World Bank must, according to the discussion paper, not only reverse their policies of promoting labour market deregulation, but actively promote inclusive and fair societies based on decent work. They describe a ‘great risk shift’, which has occurred in recent years, where that key social risks have transferred from governments and employers and on to the individual. 51

According to Ronaldo Munck, the decent work agenda however “never translated into effective measures and its credibility finally crashed in the wake of the 2008-09 Great Recession.” 52 He brands the decent work campaign as “(…) rather backward-looking, utopian and impossible to implement.” 53

Questioning the ILO’s fundamental nature, Ben Selwyn, of the University of Sussex, argues that the organization is unable to link the decent work agenda to broader human development and see beyond a capitalist system based on exploitation. Selwyn also sees signs that the ILO’s inability to enforce decent work enables elite actors such as the World Bank to co-opt its principles as strategies of brand image enhancement. 54

The notion of decent work and the concept of job creation have certainly gained ground as reflected in Millenium Development Goal 1B to ‘Achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all, including women and young people.’ But in times of financial crises and with no institution to implement decent work globally, the achievement of the decent work campaign does not seem that it will take hold in the near future.

In Europe the response to the financial crisis has primarily focused on austerity and ensuring financial stability, rather than on stimulating the economy. The usually cautious European Trade Union Confederation General Secretary, John Monks, characterized the Euro Plus Pact, the 2011 successor of the Stability and Growth Pact, in this way. The “EU is on a collision course with Social Europe…. This is not a pact for competitiveness. It is a perverse pact for lower living standards, more inequality and more precarious work.” 55 There might be a widespread acceptance of the role that job creation can play in development, and the importance of not just only the quantity of the jobs but also of their quality. However, implementing any change in the direction of the ILO’s decent work campaign cannot be seen in isolation from overall political and economic trends, as the Euro Plus Pact in Europe makes clear. -An implementation would be highly dependent on the overall political and economic power balance.

Co-readers

Dennis Arnold, Assistant Professor, Department of Human Geography, Planning and International Development, University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands

Jens Lind, Professor, Department of Sociology and Social Work, University of Aalborg, Denmark

Footnotes

- Brady, David; Andrew Fullerton and Jennifer Moren Cross (2010) ‘More Than Just Nickels and Dimes: A Cross-National Analysis of Working Poverty in Affluent Democracies.’ Social Problems 57: 560

- MacInnes, T. Aldridge, H. et al. (2013) Monitoring Poverty and Social Exclusion 2013(pdf). Joseph Rowntree Foundation, December.

- Alderman, L. (2012) ‘Ranks of Working Poor Grow in Europe.’ New York Times, 2 April 2012, p. A4.

- More information in Diamond, P. and Lodge, G. (2013) European Welfare States after the Crisis, Changing public attitudes. Policy Network Paper; See also OECD on ‘Employment Policies and Data’.

- Peschner, J. and Fotakis, C. (2013) Growth Potential of EU human resources and policy implications for future economic growth. Working paper 3/2013, European Commission.

- Arnold, D. and Bongiovi, J. (2013) ‘Precarious, Informalizing, and Flexible Work: Transforming Concepts and Understandings.’ American Behavioural Scientist 57:289.

- Kalleberg, Arne (2011) Good Jobs, Bad Jobs, The rise of Polarized and Precarious Employment Systems in the United States, 1970s to 2000s. Russell Sage Foundation, New York.

- Stone, Katherine (2006) ‘Flexibilization, Globalization, and Privatization: Three Challenges to Labour Rights in our Time.’ Osgoode Hall Law Journal 44(1): 77.

- See Lee Savage’s blog posts on ‘Living Wage in the UK’ written for the London School of Economics, in which he argues that low pay, part-time work and job insecurity – all potential negative effects of flexible markets – have prompted an unprecedented fall in living standards in the UK after the crisis. London School of Economics.

- Bernal-Verdugo, L., et al. (2012) Labor Market Flexibility and Unemployment: New Empirical Evidence of Static and Dynamic Effects. IMF Working Paper WP/12/64.

- Siebert, H. (1997) ‘Labour Market Rigidities: At the Root of Unemployment in Europe.’Journal of Economic Perspectives 2 (3): 43.

- Rodgers, G. (2007) Labour Market Flexibility and Decent Work. DESA Working Paper No. 47 July 2007

- According to Leah Vosko in her book, Managing the Margins (2010), page 5, “the SER enforced a ‘psychological contract’ premised upon shared beliefs among employers and employees about the nature of the employment relationship and mutual obligation and risk-sharing, through which employers provided workers with long-term incentives, not only offering continuity and stability but deferred pay and career opportunities, in exchange for loyalty and productivity.”

- International Labour Organization (2012) From Precarious Work to Decent Work: Outcome Document to the Workers’ Symposium on Policies and Regulations to combat Precarious Employment. ILO Bureau for Workers’ Activities, p. 31.

- International Labour Organization (2013) Global Employment Trends for Youth 2013: A Generation at Risk. ILO, p. 4.

- Ibid. International Labour Organization (2013)

- Rodgers, Gerry (2007) Labour Market Flexibility and Decent Work. DESA Working Paper No. 47, July 2007

- Louis Uchitelle argues in his book, The Disposable American: Layoffs and Their Consequences (Vintage, 2007), how economic changes in the past decades have been characterized by mass layoffs in the US economy and endemic job insecurity. In addition, Bonoli, argues that a new set of contingencies is related to the ‘post-industrial labour market’ since the 1970s. from Bonoli, Giuliano (2007) Time Matters: Postindustrialization, New Social Risks, and Welfare State Adaptation in Advanced Industrial Democracies, Comparative Political Studies, May 2007 40: 495-520.

- From Doogan, K. (2009) New Capitalism, The Transformation of Work. Polity Press: Cambridge: “David Harvey considered labour market flexibility as one of the key conditions of postmodernity. Richard Sennett’s account of work on the new capitalism considered ‘change in the modern institutional structure which has accompanied short-term, contract or episodic labour’. Manuel Castells’ Network Society described a new mode of development in contemporary society based on the new informational technologies, which lead him to conclude ‘that we are witnessing the end of salarization of employment’. Ulrich Beck’s account of The Brave New World of Work anticipated the ‘Brazilianization of the West’, which envisaged regression to some semi-feudal form of artisanal labour. Zygmunt Bauman described contemporary capitalism as profoundly individualized due to changes in the connections between capital and labour which globalization has frayed and rendered tenuous.”

- This belief is shared by Louis Uchitelle (2007) The Disposable American: Layoffs and Their Consequences, Vintage; and Ibid., Bonoli, G. (2007); and Guy Standing (2011) The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class. Bloomsbury Academic, London.

- Remery, C., et al. (2002) ‘Labour market flexibility in the Netherlands: Looking for Winners and Losers.’ Work, employment and society 16(3): 477-495.

- Kalleberg, A. (2009) ‘Precarious Work, Insecure Workers: Employment Relations in Transition’ (pdf), American Sociological Review, 74(1): 2.

- Kalleberg, A. (2009) ‘Precarious Work, Insecure Workers: Employment Relations in Transition’ (pdf), American Sociological Review, 74(1): 2.

- Bourdieu, P. (1997) ‘La précarité est aujourd’hui partout, Intervention lors des Rencontres européennes contre la précarité.’ Grenoble. 12-13 décembre 1997.

- Standing, G. (2013) ‘Defining the precariat: A class in the making.’ (pdf) Eurozine, 19 April 2013.

- Leah Vosko (2010) coins the normative model of employment, SER-centric, in which this form of employment is described as “a ‘psychological contract’ premised upon shared beliefs among employers and employees about the nature of the employment relationship and mutual obligation […] and risk-sharing, through which employers provided workers with long-term incentives, not only offering continuity and stability but deferred pay and career opportunities, in exchange for loyalty and productivity […].”

- Munch, R. (2013) ‘The Precariat: a view from the South.’ Third World Quarterly,34(5):751.

- Ibid.

- Breman, J. (2013) ‘A Bogus Concept.’ New Left Review 84:134.

- Cotton, E. (2013) We should avoid construing the proliferation of precarious work as a global catastrophe. London School of Economics blog, 4 March. Elizabeth Cotton is a Senior Lecturer at Middlesex University Business School.

- Doogan, K. (2009) New Capitalism? Polity press, Cambridge.

- Ibid. Doogan (2009).

- Industriall Union (2012) ‘Charter on Temporary Work for the Volkswagen Group.’ (pdf)

- Arnold, D. and Bongiovi, J. (2013) ‘Precarious, Informalizing, and Flexible Work: Transforming Concepts and Understandings.’ American Behavioural Scientist 57:289.

- Ibid.

- International Labour Organization (2005) Economic security for a better world. ILO, Socio-Economic Security Programme, Second Impression.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., International Labour Organization (2012).

- Diamond, P. and Lodge, G. (2013) ‘European Welfare States after the Crisis: Changing Public Attitudes.’ Policy Network, January.

- Burroni, L. and Keune, M. (2011) ‘Flexicurity: A Conceptual Critique.’ Working Paper 2.2, GUSTO Project EU

- Knudsen, H. and Lind, J. (2012) ‘De danske modeller – Plus ca change, plus c’est la même chose?’ Tidsskrift for Arbejdsliv, 14:2.

- Wilthagen, T. and Tros, F. (2004) The Concept of ‘flexicurity’: A New Approach to Regulating Employment and Labour Markets. European Review of Labour and Research10:166.

- More information on the European Guidelines and Europe 2020 Strategy for Employment is available here.

- Wilthagen, T. and Tros, F. (2004) The Concept of ‘flexicurity’: A New Approach to Regulating Employment and Labour Markets. European Review of Labour and Research10:166.

- Vosko, L. (2010) Managing the Margins

- One suggested practical implication is the idea of a basic income for all. A Swiss referendum was actually called upon in 2013 proposing a universal basic income (UBI) for all Swiss citizens – whether they work or not. This came as a counter reaction to growing income inequality and unemployment rates in the country. UBI entails that each member of society would be allowed a cash grant, basically a guaranteed income, large enough to meet basic needs of living, regardless of other sources of income. The concept has been raised in different settings and at different times, but has yet to gain momentum. Another proposed implication is the concept of ‘job guarantee’, a government programme that would create full employment. Governments would continuously absorb workers that are displaced from private sector employment, offering minimum wages. Ideally, the approach generates full employment and price stability. More information on ‘job guarantee’ can be found in Mitchell, W.F. (1998) ‘The Buffer Stock Employment Model – Full Employment without a NAIRU.’ Journal of Economic Issues, 32(2): 547-55.

- Kalleberg quoted in Evans, J. and Gibb, E. Moving from precarious employment to decent work. Discussion paper 13:9. International Labour Office; Global Union Research Network (GURN).

- International Labour Organization. ‘Decent Work Agenda’.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., Munch, R. (2013), p. 758.

- Ibid., Munch, R. (2013).

- Selwyn, B. (2014) ‘How to achieve Decent Work?’ (pdf), Corporate Strategy and Industrial Development, Global Labour Column, Number 161, January.