As supply control policies for illegal drugs achieve partial successes elsewhere, international drug markets are shifting production and transit to West Africa and the Sahel. Facilitated by limited law enforcement and border control, the drug trade has been redirected along the historical trading routes of the Sahel. Though an integrated international approach would seem logical in the current context of a worldwide ban on the drugs trade, we need to be aware that conventional state-oriented, security-minded agendas tend to harm civil society more than criminals.

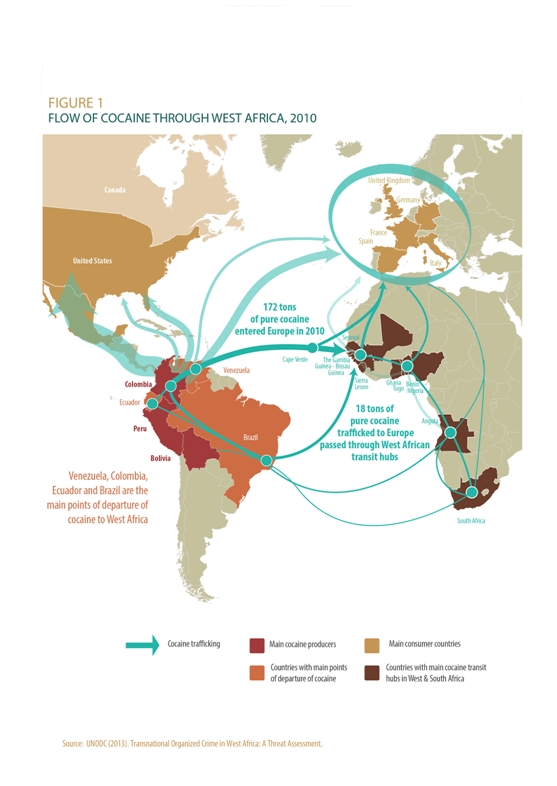

A decade ago, West Africa emerged as a major transit point in the cocaine routes from South America to Europe. This was later followed by heroin and synthetic drugs. In a briefing to the UN Security Council in July 2012, Yuri Fedotov, Executive Director the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) estimated that 30 tons of cocaine and almost 400 kg of heroin had been trafficked in the region in 2011. Methamphetamine laboratories had been found, and West Africa had become host to nearly 2.3 million cocaine users – making it not only a transit haven, but a new destination as well.

A new hub for drug trafficking

Flow of cocaine through West Africa, 2010

According to the UNODC Transnational Organized Crime Threat Assessment – West Africa 2013, estimated figures of the volume of cocaine transiting through this region soared from 3 tons in 2004 to a peak of 47 in 2007, and 18 in 2010. Three main hubs are described, one of them offshore (Cape Verde) and two on the mainland. The southern one comprises Ghana, Togo, Benin and south-western Nigeria (with cocaine transported through Niger, Algeria and Tunisia), and the northern one is centred on Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Gambia, parts of Senegal and Sierra Leone. The drug trade follows the trans-Sahara route via Mali, Mauritania, Algeria and Morocco to Europe. An eastern hub is also mentioned for air loads comprising Mali and parts of Mauritania.

In a UN Security Council debate held in December 2013, the Secretary General estimated the yearly value of cocaine transiting West Africa to be $1.25 billion. The region has become a trans-shipment hub in the cocaine trade. Furthermore, increased interdiction efforts in Turkey and other trends in the Balkan route have been identified as a factor behind increased opium and heroin trafficking through the southern route, from Afghanistan via Pakistan and Iran, East and West Africa, to the US and EU. Seizures of heroin in 2009-2010 grew from 8.5 to 35 kg in Kenya and from 104 to 202 kg in Nigeria.

Demand for recreational synthetic drugs like methamphetamine in Asia and the Middle East, particularly the Gulf, is also increasing the role of West Africa. Reliable estimates are not available for Mali or the Sahel but the World Drug Report 2013 reports a spike of cocaine seizures in Algeria. Allegedly they transited West and Central Africa prior to seizure, with air as the main mode of transportation.

Push factor: law enforcement in Latin America is leading to a shift in transit routes

The new drug hubs in West Africa and the Sahel might be the latest examples of the ‘balloon effect’, a well-known feature of international drug markets in the context of prohibition and high demand. Control strategies, particularly under the US-led ‘war on drugs’, have a supply-side focus based on crop eradication and aggressive enforcement against trafficking. But traffickers are innovative: when a route is closed down, they look for new places, routes and markets. This ‘balloon effect’ is the result of applying pressure on one point in the transnational chain of illegal drugs, simply moving the problem to another area.

Apart from suffering the adverse impact of the partial success of supply control policies in South America, more recently West Africa and the Sahel have also become affected by increased interdiction efforts in Turkey, trends in the Balkan route diverting opium and heroin trafficking, and the growing demand for recreational synthetic drugs like methamphetamine in Asia and the Middle East.

The 'balloon effect' in South America

The Latin American experience during the US-led war on drugs offers illustrative examples of the ‘balloon effect’. The term was initially coined to address the way control policies on coca cultivation led to switching between Peru, Bolivia and Colombia, but it also includes the expansion of transnational drug trafficking networks.

Initially engaged in supplying marijuana and relatively small amounts of heroin for the US, the Mexican cartels gained power through their involvement in the cocaine trade. Initially, they worked as couriers for Colombians, later they were paid with parts of the loads. As the US stepped up controls over the Caribbean routes, the importance of the mainland increased. When the Medellin and Cali cartels were defeated, the business in Colombia was decentralized. New actors lacked the connections or will to control international operations, and the centre of power for cocaine gravitated to Mexico.

By the mid-2000s, a number of trends were underway. The US cocaine market reached saturation point, while the European market was growing and spreading to Eastern Europe. Meanwhile, Mexican groups faced increased pressure under presidents Fox (2000-2006) and particularly Calderón (2006-2012). European governments deployed more efficient interdiction efforts in the traditional South America-Europe northern maritime routes to the Netherlands and Spain. The efforts were coupled with a Dutch crackdown on international flights from the Netherlands Antilles to Amsterdam airport in the early 2000s.

Cocaine routes diversified from the Andes to countries like Venezuela, Brazil and Argentina that became departure and intermediate points, particularly in the routes to Europe. The UNODC World Drug Report 2011 stated that cocaine seizures in Brazil had increased tenfold between 2005 and 2009, from 25 to 260 tons. Not surprisingly, as Brazil has a growing and vibrant economy, borders with Colombia, Peru and Bolivia, a huge coastline and established influence and trade routes with West Africa. Countries along this coastline were conveniently situated to become an ideal intermediate point in the cocaine route to Europe.

Pull factor: the strategic location of the Sahel in global trade

Why has the trade shifted to the West Africa-Sahel region, rather than elsewhere? Geography plays a critical role, as West Africa is conveniently located mid-way between South America and Europe.

But there are other factors: the region offers possibilities for drug traders to work cost effectively, using porous borders and strong informal alliances. Weak law enforcement provides opportunities to go undetected, avenues for corruption or openings for complicity at diverse levels of authority. Rather than having to set up new infrastructures, drug traders can make use of routes already paved by slave traders and smugglers, formed long before state borders were drawn. Shaped by such ancient trade routes and reinforced by cross-border social bonds and relationships, local customs have grown accustomed to the passing of people and items which are deemed to be illicit by the authorities, but seem to be a normal part of daily life and survival to many along the route.

Pull factor: local and regional conditions

West Africa and the Sahel-Sahara band have long traditions of trans-border trade in both licit and illicit goods, ranging from cigarettes and oil to people, arms and diamonds. Networks and routes are well established, as is the accommodation of grey economies into regional and sometimes national arrangements. Historian Stephen Ellis characterized the political and social environment as suitable for the drug trade, since “expertise in smuggling, the weakness of law enforcement agencies, and the official tolerance of, or even participation in, certain types of crime, constitute a form of social and political capital that accumulates over time”.

Illustrating complexity: Mali

In Mali, a complex and volatile political environment includes alliances and rivalries among Tuareg nationalists, Arab groups, northern and southern militias and – in recent years – Islamist armed actors. The country’s political elite, with its power base in the South, took advantage of ethnic tensions and controlled access to criminal proceeds to keep the rebelling northern provinces under control.

In this context, the cocaine trade triggered its own dynamics including clashes over control of profitable routes, rising tensions and the reconfiguration of political arrangements. Reportedly the trade in cocaine and other drugs expanded rapidly in the mid-2000s. In Gao and Timbuktu, Arab leaders aligned with militias created by the national leadership to protect the business. These militias were also instrumental in keeping actual and potential rebels under control. To some extent, competition over smuggling routes and consignments merged with the political interests of national and local elites. It is generally agreed that cocaine flows started to tail off by 2010, when the major kidnappings by AQIM began. The Air Cocaine incident in 2009, when a burnt-out Boeing which allegedly transported 10tons of cocaine was found near Gao, might have marked a peak in the trend. But the Malian situation became even more complicated by massive outflows of people and weapons from Libya after the NATO intervention – altering the balance of power between ethnic, militia and trafficking groups on the ground in northern Mali, leading to the internecine fighting of 2012.

How not to intervene

In “Lessons from Libya: How Not to Intervene” the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs concludes: “Among neighbouring countries, Mali, which previously had been the region’s exceptional example of peace and democracy, has suffered the worst consequences from the intervention. After Qaddafi’s defeat, his ethnic Tuareg soldiers of Malian descent fled home and launched a rebellion in their country’s north, prompting the Malian army to overthrow the president. The rebellion soon was hijacked by local Islamist forces and al-Qaida, which together imposed sharia and declared the vast north an independent country. By December 2012, the northern half of Mali had become ‘the largest territory controlled by Islamic extremists in the world,’ according to the chairman of the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Africa.”

In the global drugs trade, Mali is mainly a transit state. Local actors are related through arrangements to secure the transport of drugs through the northern deserts. Apparently, there is a short route (through Timbuktu and Kidal to reach Algeria) and a long one through northern Mali into northern Niger (sometimes via southern Algeria), Chad, Sudan, and ending up in Egypt.

In response to the creation of a new drug hub in the Sahel and West Africa, a large number of regional and international entities have become involved in West Africa, including the UN, the US and the EU, as well as individual member states and agencies like Interpol. Together with their regional partners, they take part in a range of initiatives. Initiatives have also proliferated at national levels, including the creation of specialized Transnational Crime Units (TCUs) and drug control offices.

The most relevant initiatives to counter drug trafficking

The West African Coast Initiative;

The EU Cocaine Route Programme;

The ECOWAS Action Plan on drugs (2008);

The Bamako Declaration (with practical recommendations to fight organized crime, illicit trafficking, terrorism and piracy);

The ECOWAS Counter-Terrorism Strategy and Implementation Plan (February 2013)

The African Union Plan of Action on Drug Control (2013-2017).

Purely military approaches can lead to rerouted trade and marginalized local populations

When trafficking is connected to overt violence, it attracts considerable international attention. Less attention is paid, however, to the weakening and eventual hollowing out of state structures by corruption, co-option or active complicity. Responses focus on curbing the trade of drugs using conventional drug control strategies (law enforcement and policing) or militarization of the drug war. A great deal of international cooperation is devoted to training, equipping and sometimes vetting security forces. However, experiences from Latin America have shown that purely military approaches are an incentive to reroute the drug trade to other locations. Additionally, it can further marginalize the local population by failing to address social, economic and governance reforms.

Risks of military approaches

International and regional cooperation in law enforcement and justice is essential in counter-drug strategies. Sometimes this involves the use of military means. However, partly depending on local conditions, this strategy is not without risk, as experiences in Latin America and Asia illustrate. These range from the concrete danger of providing training and equipment to elite forces that can later be drawn into the drug trade, like the Zetas in Mexico, to the further marginalization of populations and communities which may eventually bolster support for armed groups that protect their livelihoods. The effects are described in the political capital model developed by Brookings scholar Vanda Felbab-Brown, and seen in Afghanistan with the Taliban and other actors. The model challenges approaches based on narco-terrorism claims and traditional counter-insurgency operations, by stating that groups protecting the illegal economy may not only gain financial profit but also popular support.

Discussing the alleged ‘crime-terror nexus’

The narrative guiding efforts to halt the trafficking includes arguments of narco-terrorism and the ‘crime-terror nexus’. Journalistic and policy circles have depicted drug trafficking in West Africa and the Sahel as a serious threat to international peace and security. Exacerbated by the political and military conflict in Mali, a connection has been established among terrorism, transnational organized crime and drug trafficking, as in a UNSC Presidential Statement of February 2012. The US International Narcotics Control Strategy Report (INCSR) 2012 suggested that some actors involved in air and land trafficking in northern Mali “may have connections” to ethnic militias and /or extremist elements operating in the Sahel.

Though some links are undeniable, the drug-terror nexus in the Sahel has been convincingly discredited as a myth by diverse authors. Lacher has argued that groups relevant in Mali such as AQIM, MUJAO and al-Murabitun engage in – or tolerate – drug trafficking amongst other illicit activities. However, the West African Commission on Drugs concludes that trafficking is attributable to individuals and groups close to and within these organizations rather than to the organizations themselves. It is an indication that members are driven by multiple and conflicting agendas, and that other players (such as elites) are at least equally involved. By example, Lebovich states that in 2012 more narcotics passed through the part of Mali under government control than through the north. Government officials have also suggested that in the past, as much as 90% of AQIM’s finances came from ransom payments rather than trafficking. Nevertheless, international responses seem to be following a known path, with their interventions focusing on security; training national security forces and re-establishing state authority.

The latest UNODC-organized crime threat assessment for the region published in 2013 estimates, based on an assessment of cocaine seizures in Europe, a flow of cocaine declining to an estimated 18 tons. This is still a lot of money, since “the entire military budget of many West African countries is less than the wholesale price of a ton of cocaine in Europe”.

International interventions insist on security focus

The US has promoted the West Africa Cooperative Security Initiative (WACSI, closely resembling the Merida Initiative and the Central America Regional Security Initiative, though with less resources), and is providing training and equipment under the Trans-Sahara Counter-Terrorism Partnership (TSCTP). The EU has struggled to rebalance its Sahel Strategy with more security-oriented initiatives, including the EUTM Mission to train Mali security forces.

The UN Security Council has held special sessions and the security issue has entered the agenda of the Peacebuilding Commission. The most important security development in Mali was the 2013 French military deployment (Operation Serval) that officially ended in July 2014 to be replaced by a counter-terrorism operation (Barkhane). Around 1,000 French troops are assisting the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilisation Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) to maintain stability in the North.

MINUSMA is a Chapter VII operation created through UNSC Resolution 2100 of 25 April 2013, aimed to support political processes and security-related tasks. It also authorizes the French intervention force with a permanent strength of 1,000. On 25 June 2014, Resolution 2164 established the focus on ensuring security, stabilization and protection of civilians, supporting national dialogue and reconciliation, assisting the re-establishment of state authority, rebuilding of the security sector and protection and promotion of human rights.

A recent joint mission to Mali by the heads of UNODC and the Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) was intended to send “a clear message that countering drugs, crime, corruption and terrorism is essential to building peace and development in the country and region.” However, the integration of anti-drug strategies is far from perfect. The priority is counter-terrorism – and drug trafficking is considered most relevant when connected to this.

Short-sighted strategies pose problems for peacebuilding and state-building

A short-sighted strategy does not tackle corrupt elements in state structures and the role of the drug trade in decentralized governance arrangements. A lack of vision makes it difficult to find reliable local partners for peacebuilding. Disarmament and cantonment of armed groups can be obstructed, and efforts could exacerbate unequal relations between groups.

On a more general level, hardliner approaches to combating illicit economies can have unexpected outcomes in contexts with few (if any) alternative sources of income. Whilst such effects might hit the local population very hard, reportedly, they have had a relatively low impact on trafficking so far. Local actors simply change tactics in response to state collapse, political developments and external interventions. For instance, to avoid aerial surveillance, they no longer travel in big convoys.

Lessons from the past?

Experiences with the war on drugs in Latin America have triggered a debate at the highest political levels, building on the work of a vibrant civil society. Part of the discussion took place within the Organization of American States. Recently, the West African Commission on Drugs (WACD) called for a similar debate. In its ground-breaking report Not Just in Transit: Drugs, the State and Society in West Africa, it explicitly warned against replicating failed militarized policies.

Nevertheless, replicating such policies seems to be exactly what is going on. It has even been suggested that the narrative of the drug problem in West Africa is functional in guiding a certain type of policy, including a link with terrorism that allows the role of defence ministries to be widened and merge the war on drugs with the war on terror. A recent article in The Navy Times emphasizes the quiet build-up by AFRICOM, with a “focus is the vast regions surrounding the Sahara desert, the Maghreb to the north and the Sahel to the south”. It quotes Marine Commandant General James Amos who “recently said he would like to see some Marines based permanently along the West African coastline in the Gulf of Guinea.”

In Mali, analysts have warned that “if a comparison is required, the Sahel shares more characteristics with Central America and/or Mexico as a classic victim of transit trade that has empowered key players at the expense of the broader population”. But West Africa, and the Sahel, are becoming a priority area for both counter-drugs and counter-terrorism operations.

Acknowledging the complex and evolving links among illicit economies, violence and corruption

The balloon effect poses an important problem for drug producer and transit states: this illicit trade is governed by transnational dynamics, with international flows and routes dependent on market trends of demand and supply and on the strategies to combat them. Drug supply control strategies often contribute to the spread and dissemination of the problem. In Latin America, the militarization of responses has deeply damaged human security.

Efforts to halt drugs must take governance and corruption into the equation. This is a political issue, not just a technical one. The calls to simultaneously fight narcotics and terrorism with militarized and repressive strategies fail to acknowledge the complex and evolving links among illicit economies, violence and corruption, and have the potential of failing to control drugs while further undermining governance and peacebuilding.