Asymmetrical power in the Indo-Sri Lankan fisheries conflict

Sri Lankan and Indian fishermen are embroiled in an enduring dispute over the use of fishing grounds in the Palk Bay. The dispute is not only a matter of big India versus small Sri Lanka, or big boats versus small boats. Rather, Sri Lankan Tamil fishermen are less successful in asserting their interests vis-à-vis the central state than their Indian counterparts. This imbalance of political agency is grounded in enduring ethnic tension between the Tamils and Sri Lankan government.

Indian fishers have been successfully trawling in Sri Lankan fishing grounds for over a decade, which continues to have severe livelihood consequences for Sri Lankan fishermen. During the 26-year civil war in Sri Lanka this intrusion was not much of a problem, as fishermen from North Sri Lanka were restricted from fishing for security reasons . But since the cessation of the war in 2009, intrusion by Indian fishers has been highly detrimental to Sri Lankan fishers’ efforts to rebuild their livelihoods. To understand the forces at play, it is important to look at the ability of both fisher groups to assert demands on their respective political establishments. While north Sri Lankan fishermen are entangled in disempowering post-war ethnic politics, Indian trawler fishers have lobbied successfully with both the state government in Tamil Nadu, the most southern state of India, and the central government in New Delhi. These differences stem from the fact that fishers on the Indian side successfully apply political agency through tapping into larger discourses of regional political autonomy, while the same political discourses limits mobilization options for their Sri Lankan counterparts.

Background

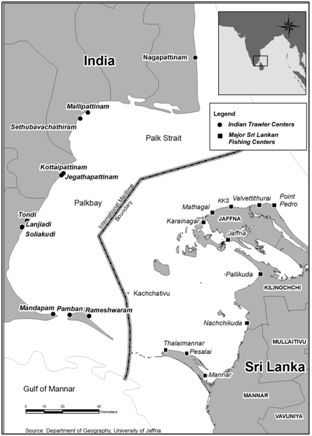

The shallow Palk Bay (see figure 1) is the scene of a protracted transboundary fisheries conflict between trawl fishers from the Indian state of Tamil Nadu and small-scale fishers from Northern Sri Lanka, who are both dependent on Palk Bay’s limited fishing grounds. Tamil fishermen in Northern Sri Lanka were restricted from fishing for most of the 26-year civil war, but have been slowly rebuilding their livelihoods over the past few years in the midst of a highly militarized environment. Aided by significant state subsidies, the Indian trawler fleet in the region expanded during the civil war period from a few hundred to approximately 1,900 trawlers, part of them filling the vacuum of the rich but abandoned Sri Lankan fishing grounds. Over the years, Indian fishers became dependent on Sri Lankan waters to secure a profitable catch: if fishing in Sri Lanka were to be stopped most Indian trawler fishers and those dependent on allied fishing activities would be highly affected. Sri Lankan fishers, on the other hand, are furious about Indian trawlers fishing in their fishing grounds: they point out that trawlers not only turn the rich marine ecosystem into a marine desert, but also prevent them from fishing as their nets get damaged by Indian trawl nets. It is worth noting that, on the Indian side, the trawlers also have conflicts with Indian small scale fishers, although local institutions have provided for some level of co-existence.

This article is based on research conducted by Joeri Scholtens, Johny Stephen and Ajit Menon, and is part of the ‘Reincorporating the excluded (REINCORPFISH)’ research project of the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research – WOTRO Science for Development (‘NWO-WOTRO’) programme, ‘Conflict and Cooperation over Natural Resources in Developing Countries (CoCooN)’.

The findings presented are based on one and half years of fieldwork in Northern Sri Lanka (first author) and Southern India (second and third author). Primary research was based mostly on open and semi-structured interviews with fishers and fisher leaders, and complemented with a household survey (N=1020) in Northern Sri Lanka. In addition, newspapers were monitored during 2011, 2012 and 2013 to keep track of continuously unfolding political events related to the fisheries conflict within and between the two countries.

It would be naive to perceive this livelihood conflict in isolation of its polarizing political context. This fishing conflict takes place against the background of the recently ended civil war, which was fought between the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and the Sri Lankan government armed forces from 1983 to 2009. Since 2009, the Sri Lankan government has pursued a policy of redevelopment with an important role for the military in governing society. According to many observers, this is perpetuating ongoing grievances for the Tamil population and compromising any potential for reconciliation. Internationally, a pro-Tamil lobby with strong nationalist tendencies, led by a sizable diaspora and sympathizers in Tamil Nadu (a state of 74 million people) has been continuously exerting pressure on the Sri Lankan government to take steps to address alleged war crimes, stop ongoing Tamil marginalization, and decentralize more powers to Tamil majority areas by way of the 13th Amendment to the Sri Lankan Constitution, which created Provincial Councils.

Palk Bay was an important location during the civil war with the Sea Tigers (the sea division of the LTTE) battling the Sri Lankan Navy there and with goods, war supplies and people being smuggled up and down through the Bay to Tamil Nadu. A crucial thing to understand is that both fisher groups are Tamil, sharing a long history and familial and cultural ties that resulted in moral support for the Tamil Eelam struggle from Tamils in Tamil Nadu. During the civil war, fishing in Sri Lanka was not without risk for Indian trawlers because a vigilant Sri Lankan Navy often found it difficult to distinguish between Sea Tigers and fishermen,1 the former often attacking them. While there are claims and counterclaims as to who was responsible for the deaths of over 200 Indian fishermen,2 what is clear is that these deaths reinforced strong anti-Sinhala sentiments in Tamil Nadu. In the aftermath of the war, while the Navy has engaged in regular token arrests and Indian fishermen do report occasional harassment, it appears to be no longer a matter of life and death.

The Palk Bay is divided by an International Maritime Boundary, which was bilaterally agreed upon in 1974. Although the agreement was ambiguous about the fishing rights of Indians, there is widespread consensus that the Sri Lankan fishermen have legal and moral right on their side and that Indian trawling should be reduced. Yet the status quo of approximately 1,000 boats fishing regularly in Sri Lankan waters has hardly changed over the past few years.

Power asymmetries

Indian ‘encroachment’ into Sri Lankan waters can be explained by two key structural power imbalances. The first is that between the two nation states, with India being the regional superpower and Sri Lanka less able to assert its sovereignty over its sea resources. Sri Lankan economy and politics are tightly intertwined with those of India, and confronting the ‘big brother’ by arresting its fishermen can easily boomerang. The second visible imbalance is that between the powerful Indian trawl engines, and the much smaller Sri Lankan ones. When fishing at the same place at the same time, especially during dark nights, Indian trawler nets invariably damage or destroy the nets of Sri Lankan artisanal fishers.

Yet, such a limited explanation of encroachment ignores the everyday lived politics and the dynamic power relations between the two fisher communities and their respective states. In order to understand these dynamics, it is important to take into account the differences in political agency (see box) and to put the conflict in the larger historical and political context of the Tamil struggle for autonomy, and the deep Sinhala fear of that being realized.

Power as political agency

Within the context of this article, power is understood as political agency, defined broadly as a ‘variety of individual and collective, official and mundane, rational and affective, and human and non-human ways of acting, affecting and impacting politically’.3 Political agency is an important phenomena, as ‘[i]t is through agency that contradictions potentially get suspended and change occurs’.4

We understand political agency as individual or collective ability to attain ideological or material needs from a political establishment. In this sense, political agency is the ability to participate in and influence political processes.

Indian fishermen and political agency

Indian fishermen, have been able to demonstrate their agency with a fair bit of success, resulting in them maintaining their fishing grounds in Sri Lankan territorial waters. They exert their collective agency primarily through boat owner associations, caste associations, the Church and political parties. This has manifested itself in a number of ways.

1. Significant regional autonomy. Regional (i.e. state level) politics in federal India enjoy significant autonomy, forcing the central government in New Delhi to be attentive to local sensitivities. Fishermen are well represented in every major political party and are actively involved in local party politics. By getting politically involved, fishers are able to articulate their concerns both at state and central level.

2. Space for political dissent. Despite the limits of parliamentary democracy, fishers are able to articulate their voice. The issue of Katchatheevu, a small island in the middle of Palk Bay,5 has been one rallying point. While fishermen are fully aware that retrieving Katchatheevu alone in no way can help their fishing interests, the space of resentment this issue has created makes it an ideal political arena for fishers to express their frustration that the central government has paid inadequate attention to their plight.

3. Demand for the right to life and livelihood. The killing of no less than 200 Indian fishermen has angered fishers and the general public in India. Though the incidence of violence has been significantly reduced since 2008, public debate in India and more particularly in Tamil Nadu continues to highlight the unjustified killings. The alleged killings and the harassment of fishers by the Sri Lankan navy feeds into larger anti-Sri Lankan sentiment in Tamil Nadu, giving political leverage and agency for fishers to place their demands.

4. Linguistic and ethnic politics. There are different opinions on how and why India became involved in the civil war in Sri Lanka.6 Nevertheless, it is clear is that incumbent state governments in Tamil Nadu have sympathized with the cause of the Sri Lankan Tamils due to their shared linguistic and ethnic identities. State policies, like the resolution passed in the Tamil Nadu legislative assembly condemning war crimes in June 2011 and demands on the central government to stop treating Sri Lanka as a friendly country, are examples of moral support from Tamil Nadu for the Eelam cause. Since the end of the war there have been allegations by political parties in Tamil Nadu against the central government for colluding with the Sri Lankan government and acting against the interest of Tamils both in Sri Lanka and India. These allegations are typically substantiated by citing the inaction of the central government in intervening to save the fishers in Palk Bay from the Sri Lankan navy.

Sri Lankan fishermen and political agency

Although fishermen in Northern Sri Lanka are remarkably well organized in a cooperative system that survived the war and enjoys a close to 100% membership, the ability of these organizations to lobby for the collective interests of fishermen, especially in comparison with their Indian counterparts, has been increasingly undermined for a number of reasons.

1. Post-war militarization. The recent militant history of the LTTE provides the state with a justification for post-war militarization, and close scrutiny of any form of collective Tamil political action. Thus, when a local NGO put in a serious effort to strengthen fisheries leadership in the North, politicians as well as intelligence were quick to marginalize these efforts by preventing meetings from taking place and ensuring non-participation of fisher leaders. Fishing leaders are careful and reluctant to stand up for fear of repercussions.

2. Sense of powerlessness. Somasundaram and Sivayokan point out that 26 years of war has inflicted damage on people’s belief that they are able to influence politics.7 A sense of powerlessness prevails that largely prevents collective political action against Indian trawlers. Fishermen have become disillusioned by the uselessness of earlier collective efforts to oppose Indian trawlers. For example, while fishers have on occasion hijacked Indian trawlers at considerable risk and written countless petitions to various political channels, they have not received positive feedback for their actions.

3. Perception of anti-Tamil conspiracy. Fishermen generally believe that the Sri Lankan government has an interest in allowing the status quo, i.e. Indian encroachment, to prevail because it undermines the Tamil economy in the North and creates a welcome breach between the Tamils of both countries. The Sri Lankan state is arguably wary of transboundary Tamil cooperation, given a long time fear of being dominated by the demographically dominant Tamil population. Regardless of whether such fear bears any truth, North Sri Lankan fishermen’s framing of Indian encroachment as a government conspiracy against the them reinforces the sense of powerlessness This perspective also inhibits any constructive conversation between the Sri Lankan government and the fishermen which again reinforces the same distrust.

4. No appealing story to tell. Fishermen face a devil’s dilemma when it comes to focusing the direction political agency should take: while wanting to limit Indian fishers’ encroachment, they do not want to allow the Sri Lankan state to capitalize on inter-Tamil strife. This inhibits them from telling a clear-cut and convincing story of their plight, i.e. one that aligns with the interests and discourses of any of the powerful parties.

5. Caste politics. Caste plays a crucial role in Northern Sri Lankan Tamil society. Fishers are considered inferior to the political land-owning farmer caste that dominates the Tamil National Alliance (TNA). Although the recently elected TNA government in the Northern Province has spoken of fisher rights, it remains to be seen whether lobbying against encroachment of Indian fishermen will be a priority, given its potential to compromise the larger Tamil political struggle for autonomy.

Asymmetry of political agency

Although both fisher groups are well organized, Indian fishermen are better able to use the political space offered by regional ethnic politics. They are able to build on the prevailing ethnic tensions in the region in order to politicize their plight, while on the other hand the space for Tamil Sri Lankan fishermen to express their demands is more limited. Any effort to explain the nuances of how Sri Lankan Tamil fishers are affected by their Indian Tamil counterparts is marginalized in the meta-narrative of Tamil versus Sinhala produced by the civil war and its aftermath.

This asymmetry of agency, however, is not static but rather continuously renegotiated, not least at the time of writing this article. Sri Lanka has just held the first elections in the Northern Province for 25 years, resulting in the victory of the TNA party. Although the newly elected TNA provincial government has already spoken about the plight of the fishers in the North, it is yet too early to judge how this victory might translate into any increase of agency on the part of Sri Lankan fishermen. At the same time, in recent months the Sri Lankan Government has significantly increased the practice of arresting Indian trawlers, apparently feeling the pressure to assert itself on the fishing issue more proactively. Arrests of Indian fishers and seizure of trawlers, from one perspective, could be seen as a positive development as it may provide necessary impetus to get important actors (especially the state government of Tamil Nadu) to react in ways which address cross-border fishing, something it has been loath to do thus far. On the other hand, however, these arrests are creating an increased sense of despondency amongst Indian fishers. This suggests that even though trawler fishermen have political agency with the Indian state, they certainly do not with the Sri Lankan government.

Depoliticizing the conflict?

From the outset, this fisheries conflict between two groups of fishermen with a shared cultural background, mutually supportive political positions and sophisticated levels of internal organization, appears to be a case where resolution is possible by means of mutual dialogue. It has proved, however, to be more complicated. NGOs’ efforts to build the capacity of Sri Lankan fisher leaders have been effectively blocked by Sri Lankan authorities; efforts to organize dialogues between Sri Lankan fisher groups and the Sri Lankan state have been met with deep levels of suspicion and reluctance on both sides; and efforts to organize dialogues between fishers from both sides, though initially promising and rewarding, were later subsumed within the larger political priorities of the respective states. Given the deep entrenchment of this fisheries conflict in regional politics, and the suspicious attitude of both India and Sri Lanka towards any third party mediation in ‘internal disputes’, it is questionable indeed what role an outsider has to play here, if any.

Some experts have suggested that the only promising way to adequately deal with this conflict is to disconnect it from its polarizing regional politics. In a utopian world, this isolation would allow fishermen and governments to sit together to see how a fair and sustainable allocation of fishing rights could be arrived at in the Palk Bay. However, in the real world, isolating natural resource conflicts from its larger socio-political context provides a dilemma. By making Palk Bay fisheries governance ‘apolitical’ and pursuing constructive multi-level dialogues, outsiders run the moral risk of being silent about Tamil grievances in Northern Sri Lanka. Similarly, ignoring the interconnectedness of fishing issues runs the risk of making interventions superficial and hence ineffective, leaving the elephant in the room unaddressed. The choice, therefore, is between the devil and the deep blue sea.

Want to read more on the fishing dispute in the Palk Bay? Read the blog post by Ahilan Kadirgamar in The Broker’s Power and natural resources debate.

Co-readers

Ajit Menon, Associate Professor, Madras Institute of Development Studies, Chennai, India.

Aklilu Amsalu, Assistant Professor, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Daniëlle Hirsch, Director, Both Ends, Amsterdam Netherlands.

Domien Huijbregts, Communications Officer, NWO-WOTRO Science for Global Development, The Hague, The Netherlands.

Frans Bieckmann, co-founder, executive director and editor in chief, The Broker, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Teyo van de Schoot, Human Rights Senior Advisor, HIVOS, The Hague, The Netherlands.

Footnotes

- Suryanarayan, V. and Swaminathan R. (2009) Contested Territory or Common Heritage? Thinking Out of the Box. Madras: Ganesh and Co Publishers

- Vivekanandan (2011) The Plight of Fishermen of Sri Lanka: The Legacy of Sri Lanka’s Civil War. Paper submitted to Centre for Security Analysis.

- Hakli, J. and Callio, K.P. (2013) Subject, action and polis; Theorizing political agency. Progress in Human Geography. January 22:1

- Cox, K. and Low, M. (2003) Political geography in question. Political Geography 22: 601

- Katchatheevu is a small island in between India and Sri Lanka which was given to Sri Lanka in 1974 when the boundaries in Palk Bay were demarcated through a bilateral agreement between the governments of India and Sri Lanka. According to some observers (for example, Suryanarayan, V. (2004): Conflict over Fisheries in the Palk Bay Region. New Delhi: Lancer Publishers and Distributors) the interests of Tamil Nadu were not taken into consideration when this agreement was made. The 1974 agreement, however, has a clause wherein the fishers from India are partly allowed to use the island for fishing purposes. The Indian government’s reluctance to listen to the state government in Tamil Nadu is still viewed as a betrayal by many people in the state including fishers.

- Shankaran K (1999) Postcolonial Insecurities: India, Sri Lanka, and the Question of Nationhood. University of Minnesota Press.

- Somasundaram, D. and Sivayokan, S. (2013) Rebuilding community resilience in a post-war context: developing insight and recommendations – a qualitative study in Northern Sri Lanka. International Journal of Mental Health Systems 7(3):1-24