Since 2012, Mali has been suffering from what at first seemed to be a sudden outbreak of armed conflict which eventually led to a military response by France. At that moment, the conflict was framed predominantly as a battle against the rise of extremist Islamism. More international community actors now recognize that other perspectives need be taken into account to fully understand the dynamics of this conflict. Yet do we have a good overview of relevant perspectives? The Broker aims to identify, integrate and analyse the different perspectives to advance insights into the constantly changing dynamics in Mali and the Sahel. We are able to do this with an updated analysis from experts in combination with on-the-ground knowledge. We like to call this a ‘living analysis’.

What is new in the living analysis?

Read more about the latest updates in this living analysis.

- On 10 February, five civilians were killed and eighteen wounded when their vehicle struck a landmine in Central Mali. our civilians were killed in an attack by suspected islamist extremists in northern Mali. For more detailed information on the latest conflict developments, please see our slide: Updates on the conflict.

- On 1 Februari, a report published by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and MINUSMA expressed concerns over human rights violations, it reports more than 600 human rights violations between January 2016 and June 2017. For more detailed information on the peace process, please see our slide: Updates on the peace process.

- GIZ’s Bernadette Schulz, Martina Bail and Laura Kollmar discuss the response of the African Peace and Security Architecture to the outbreak of conflict in northern Mali.

- A number of author’s discusses trade-offs between economic development and governance in relation to youth employment.

- Amagoin Keita reacts to Marije Balt’s discussion of youth employment and insecurity by arguing that decentralization needs to be taken to the community level.

- Have a look at our detailed explanation of who is who among the armed groups, featuring an infographic detailing their historical development.

- Our interactive map is updated each month! It tracks violent incidents throughout Mali.

- Also have a look at our interactive resource list, it is updated periodically with the latest literature and reports used in the Sahel Watch programme and suggested by our expert contributors.

What is a living analysis?

Read more about the living analysis method.

There is a violent outbreak in the north of Mali. The media reports that it is another Tuareg rebellion, but are there perhaps other ways to look at this conflict? Our aim is to give an overview of existing knowledge and to take a multi-perspective view that enables us to contextualize what is happening on the ground. There are two key elements in our approach, one is the overview and synthesis of perspectives and the second is generating knowledge together with many experts, including local voices. The Broker’s analysts are constantly investing in these sources. This is a beta version to test and improve our living analysis method.

Sahel Watch starts by analyzing the regional dynamics of the conflict in Mali. This will later be extended to the larger Sahel region, where similar issues are relevant. This living analysis is an innovative way of structuring knowledge. It is easily accessible and can be reproduced and extended to analyze different conflicts. It is a tool for clarifying the different perspectives on the complexities of conflict, where they agree and where they differ. It gives an overview of existing knowledge and integrates the views of experts. In the links you will find up-to-date expert opinions, videos, information from the ground and an overview of relevant academic and policy reports, literature and media coverage. At The Broker, we use this as input for expert meetings, to generate discussion and strengthen information-sharing partnerships.

If you are interested to contribute to the co-creation process towards a more qualitative analysis, please email karlijn@thebrokeronline for your input. The analysis will be updated in response to the changing dynamics of the conflict, and frequent briefings will be distributed on the updates. You can subscribe to the frequent updates here.

Dynamics of the armed conflict in Mali (a security perspective)

Mali was once considered a model democracy but in early 2012 it suddenly collapsed after a separatist rebellion by the Tuareg Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA). A civil war was unleashed, predominantly in the northern part of the country. Regionally-based extremist Islamist groups took advantage of the unrest in the north and a weakened Malian army overthrew the weakened, indecisive and corrupt Malian government. When the armed Islamic groups advanced on the capital of Bamako, a French military intervention returned a fragile control, allowing the establishment of an interim government and an international peacekeeping force.

Read more: African responses to the eruption of conflict

From the beginning of the attacks by Tuareg rebels and Islamist groups from the North in 2011, ECOWAS intervened diplomatically aiming at establishing a dialogue between the rebels and the government. After the military coup, which, according to the putschists, was a reaction to the government’s inability to defeat the rebels, ECOWAS reacted immediately. Mali’s ECOWAS membership was suspended, shortly after it was suspended by the AU, which illustrates the rejection of the self-declared government by the two regional bodies. ECOWAS also succeeded in mediating the formation of an interim government led by the putschists and the former Malian government in the short span of two weeks. The African-led support Mission to Mali (AFISMA), a mission planned by ECOWAS already in 2012, was deployed alongside the French Operation Serval and Chadian troops, following a foray by rebel forces in January 2013. Read more.

Bernadette Schultz, Matina Bail and Laura Kollman are co-authors of the living analysis.

The accumulated challenges are undermining the government, the economy, and the livelihoods of the Malian people. The government is still relying on these international intervention forces such as the UN’s Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) as they are currently providing stability in the north. Initially, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) organized the African-led International Support Mission to Mali (AFISMA), which was supported by the African Union and the UN Security Council. However, the French intervened and when AFISMA deployed earlier than planned it was criticized for lack of capabilities and resources. MINUSMA quickly took charge and coordinated military operations, overshadowing ECOWAS and the African Union.

Read more: a distant and ungoverned northern territory.

The French were able to use superior conventional forces to repulse a conventional offensive and recapture territory but they have not so easily been able to hold that ground against the asymmetric and unconventional tactics of a dispersed terrorist adversary. Read more.

During my stay in Tegharghar, in Kidal province near the border with Algeria, in 2005, I witnessed training camps, Madrassa (Koran schools) and tunnels. It appeared a very well organized system, with connections to the capital Bamako. I learnt how the extremist recruited people, fitted to their specific work needs. I also learnt that they had a deal with Djandjawids (fighters from Sudan), Al-Qaida, Ansar El Sharia, Saharaoui Democratic Republic fighters and the Boco Haram group. Read more.

Operationally, Boko Haram is supplied with arms through two main channels. Firstly, by retrieving them from the arsenals of the Nigerian security forces during armed attacks. Secondly, through joining regional networks of arms trafficking. Read more.

These are co-authors of the living analysis.

France, the former colonial power, remained militarily present from 2013 onwards under Operation Serval, fighting against Islamist extremists throughout the Sahel region. Operation Serval was taken over by Operation Barkhane, which focused on creating local capacity to safeguard security. France and other European countries present want to reduce their troops in the region, in the hope that future stability will be provided by the G5 Sahel joint force (FC-G5S). The G5 is a collaboration between Mauritania, Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger and Chad and is supported by the UN. It aims to combat terrorism and drug trafficking, restore state authority, and facilitate humanitarian operations and development programmes. All the while, violence between armed groups in northern Mali continues, while an Islamist extremist insurgency spreads throughout the country.

Development and human needs (a socioeconomic perspective)

The Sahel is one of the most difficult places on earth to survive. The northern part of Mali, with borders deep in the Sahara desert, has dealt with severe drought, food and water scarcity in recent years. Most Malians (over 90% of its 15 million people) thus live in the south of the country, mainly in the capital of Bamako. Even so, 43.6% of the population still lives in poverty where economic opportunities are limited and infant mortality and illiteracy rates are high. Furthermore, 48% of the population is younger than 15 years old and life expectancy is around 55.

Read more: the Malian economic climate.

Regarding Mali’s economy, southern Mali has developed a cotton and rice industry by using water from the Niger and Senegal rivers. The north is home to nomadic herders, many of which are agropastoralists who raise livestock in the dry season and grow crops in the rainy season. Mali is also Africa’s third largest gold producer, which accounts for 80% of its export earnings. Other natural Malian resources include uranium, phosphates, kaolinite, salt and limestone. In addition, the country is often characterized as a ‘donor darling’ because it was presented as a model of democracy in the region, leading to a significantly higher investment of aid money. Such aid eventually amounted to 27.6% of the state’s general budget between 1996 and 2005. However these policies are said to have contributed to a culture of corruption that hampered progress both in governance and economic development, which indirectly contributed to Mali’s crisis.

Read more: trade-offs between governance and economic development.

Getting the economy back on track in the post-conflict environment of Mali is not an easy task. However, with the increased sense of security, individuals are exploring new opportunities to venture into economic activity. Regaining trust is a long and sensitive issue, but improvements are being made. State and other institutions are becoming less ambiguous, and although corruption levels are high, we see a change of attitude and a restoration of trust. The rule of law is being reinstated in most areas in Mali, making rules less open for various and different interpretations. This increases the predictability of actions, which is crucial for any form of economic development. Read more.

Several recent studies (study by DLP and a study by DFID) seem to have no qualms in indirectly complying with authoritarianism, nepotism or corruption as byproducts of developmentalism (‘going with the grain’) or ‘developmental patrimonialism’. The World Bank is a faithful ally in this venture. This seems to be partly an answer to the challlenge of the ‘Chinese model’, and the approach implies that as long as results are delivered (such as GDP growth, constructing big dams, building markets and value chains, ‘capacity building’), autocratic developmentalism is all fine and well. The assumption seems to be that poor people do not need democracy, environmental justice, human rights or respect in the juridical sense: that’s all just secondary to ‘poverty eradication’. Read more.

There are two reasons why young people – mostly boys – in forgotten areas in Mali, Nigeria, Kenya and Somalia join militant “jihadi” extremist groups that commit acts of terror. Firstly, hunger and unemployment make people receptive towards promises and money offered by these groups. But the second factor is perhaps even more important: bitterness and anger vis-à-vis mostly corrupt and callous local governments and local elites. The fact that such unjust, uncaring and often oppressive local rulers are usually supported by Western countries with billions in military and development aid creates an anti-Western sentiment that is easily tapped into by “jihadi” PR. Read more.

The right ingredients for a ‘revolution’ against corrupt and dictator-led governments are present in Central Africa, which include an internationally connected youth population that isn’t afraid to protest. Read more.

ICTs are not just a way of disseminating knowledge of local power conflicts to the outside world, they also feed local communities with images of global political and social transformations and ‘modern’ consumption patterns. These images affect the aspirations of local youths. The use of violence is not always part of a carefully planned political trajectory, but is sometimes, or at the same time, an expression of frustration at the unattainability of the ‘modern lifestyles’ these young men (and women) witness through the use of ICTs, but cannot access. Read more.

These are co-authors of the living analysis.

Environmental degradation and water shortages heavily undermine access to resources and economic activities and have caused desertification, deforestation, soil erosion and inadequate supplies of water. 1 Droughts are frequent yet from June to December the Niger River floods and creates the Niger Delta. This critical water flow is under threat from dam building and hydropower and also affects downstream countries of Niger, Benin and Nigeria. This ecological stress has only added to the conflict of interest regarding access to water resources and the challenging survival of various ethnic groups.

Read more: droughts in the Sahel, diminished space for nomadic groups, and regional migration

As seen in the 1970s and 1980s, periods of drought in the north resulted in diminishing space for nomadic groups. This increased conflict over fertile land as large groups of nomads depend on declining areas of fertile ground. Little water and lacking fertile land have resulted in overgrazing and desertification where soil cannot fully recover. After successive periods of drought in Mali, large numbers of Tuareg, a population that extends from Algeria to Libya, fled to these neighbouring countries. International action to improve their health, economic status and security has in some cases further fuelled tensions between ethnic groups.2

Many countries in the Sahel region have to endure these conditions, suffer from the conflict and be classified as a ‘fragile’ state. Conflicts also spill over regionally between these countries. For example, the 2012 food crisis in Niger was ‘compounded by instability in neighbouring Mali and the inflow of tens of thousands of people fleeing from the conflict there’ as was stated by the Human Development Report. Instability in Libya has had consequences for Mali and vice versa, which resulted in a persistent stream of refugees that took the trans-Saharan route via Mali and Libya to Europe. Other unstable countries in the region that are at rick include Burkina Faso, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and South Sudan.

Mali: transit point for trans-Saharan trade (an (illicit) trade perspective)

Historically, people in the Sahel have coped with economic uncertainties by participating in informal and cross-border trade networks.3 An important resource for such informal trade is Algerian subsidized foods. Today, Mali is an important departure and transit country for migration, both for migrants traveling to northern Africa or Europe and for trans-Saharan destinations. Almost 150,000 Malians have fled to neighbouring countries since January 2013. Communities that have traditionally been engaged in trans-border businesses, such as the nomadic Tuareg and Tebou have monopolized these Saharan trade routes.

Read more: illicit trade in the Sahel-Sahara

However the benefits of informal cross-border trade and trafficking certainly favour the elite. Local business elites cooperate with armed groups by maintaining control over trafficking routes and over the years criminal networks have formed along the trans-Saharan routes in smuggling cigarettes, people, weapons, drugs and food. Europe’s new drug route as originated from Latin America and passing through West Africa has created an especially large impact on the local economy. For example, Cité du Cocaine, an exclusive neighbourhood and haven for smugglers’ villas in Gao, was well established before conflict broke out. Military responses to the illegal drug trade in Latin America have caused a ‘balloon-effect’ where suppressed trafficking routes are being rerouted through territories with little government presence.

Read more: trafficking along the Saharan trade routes

The region offers possibilities for drug traders to work cost effectively, using porous borders and strong informal alliances. Weak law enforcement provides opportunities to go undetected, avenues for corruption or openings for complicity at diverse levels of authority. Rather than having to set up new infrastructures, drug traders can make use of routes already paved by slave traders and smugglers, formed long before state borders were drawn. Shaped by such ancient trade routes and reinforced by cross-border social bonds and relationships, local customs have grown accustomed to the passing of people and items which are deemed to be illicit by the authorities, but seem to be a normal part of daily life and survival to many along the route. Read more.

The extraordinary opportunity to permeate ‘fortress Europe’ thanks to the chaos in Libya is proving a strong siren song for West Africans. Their route to the North African coast requires traversing the treacherous Sahara – which is impossible without a smuggler. An estimated 3,000 people are travelling through Agadez in Niger each week, with each one paying an average of US $800. The nomadic groups that have long trafficked and smuggled people along the trans-Saharan trails are using these windfall profits to consolidate their control over routes. The result is a rise in state corruption and violence, driven by competition as well as new inflows of cash for the region’s various armed groups. Read more.

Although the conditions for the Tuareg’s transnational border business have become more difficult, afrod will continue, as the inner-Saharan traffic is not administered by states, nor is the food supply sufficiently organized by the Nigerien (or Malian) government. As long as there are no legal possibilities for immigrating to the EU, this clandestine business will go on as before. The EUCAP Sahel Niger (European Union Mission in Niger) reception camp planned for migrants in Agadez will most likely try to stop the transa system to suppress migration to Europe. But, for the Tuareg, this would imply an increasing interest in the afrod route and need for their logistic support. Read more.

Locals were initially employed to guide the way, leading convoys to water and fuel dumps in the desert. The rise of cocaine trafficking made the Saharan trade route much more lucrative. Unemployed youth in particular have eagerly taken up opportunities to make the dangerous journey trafficking cocaine. This is not isolated to Mali. Across West Africa, a long line of young people are willing to risk trafficking small quantities of cocaine to Europe, with many couriers arrested in airports along the coast and in Europe. The ability to make fast money from drug trafficking means it is often seen as a good thing by communities that benefit. But the revenues from drug trafficking are often captured by elites with drug couriers paid very little considering the risks they take. Read more.

While evidence directly connecting extremist Islamist groups to the drug trade in particular is tenuous, several prominent leaders of these groups, in particular the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO in French) are reportedly linked either directly or through family members to the drug trade, while some AQIM leaders such as Abdelkrim al-Targui (Hamada Ag Hama) purportedly engaged in activities such as smuggling and kidnapping alongside Islamist militancy, with the latter in particular providing a huge source of funding for militant groups. And regardless of the extent to which funding from criminal activities other than kidnapping aided extremist Islamist groups and pro-independence movements, their presence in the region and corruption in Bamako helped degrade governance and create an environment of permissiveness and ‘remote control’ governance that pushed state structures to a point of collapse. Read more.

These are co-authors of the living analysis.

A large part of the population in northern Mali depends on the regional informal economy for basic services and security. Yet the political elite have shaped the system in such a way that public funds and the accumulation of wealth became monopolized through informal channels of patronage.4 Conditions in Mali were even more favourable to the drug trade than those in coastal West African states, like Nigeria with its presence of international ports.

Security sector weakness and failed reforms (a governance perspective)

This perfect storm of weak state control moulding itself into an established regional informal economy did not happen overnight. In fact, when gaining independence from France in 1960 the Malians inherited a highly centralized state as based on the French model which relied heavily on local elites and their connection to Bamako to rule the northern periphery. The colonial state exclusively educated black southerners for the ruling class who now had to assert their control over the north. They did so using a combination of tactics including favouritism, patronage, economic marginalization, military control and divide and rule strategies.

Read more: insecurity worsens

a study done of border security and management in the Liptako-Gourma border regions between Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso revealed that, despite the strong trust in the government, security concerns are first addressed using traditional conflict mitigation mechanisms, and the authorities (who may be present, but are largely unresponsive) are approached only as a last resort. This shows that the governments of these countries are unable to effectively control their remote border regions and utilize or prioritise border communities in addressing transnational challenges. Read more.

The monopoly on violence is weakened and poorly paid and equipped soldiers might choose their own interests over that of the state. If the MINUSMA mission in Mali is anything like previous peacekeeping missions in the region, it could be followed by an increase in instability in countries like Chad and Nigeria which have sent troops to participate in the international force. Read more.

Democracy has made great strides in the region since the 1990s. At present, perhaps the only West African countries that are not serious about this are Togo and the Gambia. But in general, democracy has only created different incentives for what remains the priority of many rulers in the region: the protection of their power and regime, even against the requirements of economic development, social progress or state-building. ECOWAS can suffer from this, when – as has recently been the case during an ill-starred coup attempt in Burkina Faso – it appears to side with regimes against the people. More fundamentally, most West African states are captive of regimes that feel threatened by a strong state – that is, a state in which technical and political institutions enjoy the level of operational autonomy vis-à-vis the executive power required by their optimum efficacy. Authoritarianism dreads constitutions and an efficient state because these come with laws and rules that hedge and regulate its power. Read more.

How do you find the right individuals to support? Seeking for local leaders may lead you to Nelson Mandelas, but you can also find the next Joseph Kony. How do you make sure this form of support is inclusive? It starts with understanding the political economy of Mali’s security sector and integrating local leaders of the customary system. According to Seth Kaplan, fragile states have limited commitment mechanisms that hold backsliding major players accountable. Thus, it is advisable to promote an open and political process with horizontal relationships between the state and various ethnic, religious, clan and ideological groups to facilitate open debate. Connect the youth, as the political aspirations of youth are vital for stability. Read more.

These are co-authors of the living analysis.

After becoming an independent nation, Mali suffered from several coups d’état until a multiparty democracy was established in 1992 with a newly elected president. During the past 30 year dictatorship, the autocratic and military-style rule in the north only exacerbated distrust between the north and the south. The policy of co-opting or buying northern elites, all the while ignoring social and economic issues in favour of repression, continued even after democracy was established. This policy continued throughout President Amadou Toumani Touré’s (2002 – 2012) term, who treated the Malian territory as a mosaic of fiefdoms where powerful actors could operate with impunity as long as their superiors received a piece of their earnings and activities. Needless to say, trust in state institutions is generally low among Malians.

Video 'Ganda izo: the Fulbe Self-defense group in northern Mali'.

In 2012, a rebellion in the North of Mali created a situation of complete insecturity. The Malian state fled the region and the people were left to their own devices. As a reaction ethnically organised groups of self-defense were created .

This video lets two of the leaders of Ganda Izo militia talk about the insecurity which led them to organise themselves to defend their people.

Mali previously initiated a programme of decentralization that was already enshrined in its constitution at independence. The 1990-1996 Tuareg rebellion led to the government making serious work of this reform, first to placate the Tuareg’s in the north and then extending it throughout the entire country. This devolution process was accompanied by a process of security sector reform, however security and judicial services were never sufficiently established and corruption only remained rampant. At the end of the rebellion in 1996, Tuareg armed groups were either disbanded or integrated into armed forces. Yet a feeling of disadvantage continued to exist amongst certain groups in the north. A defection of a small number of Tuareg soldiers from the Malian armed forces and spill over violence from the Tuareg rebellion in Niger led to further violence in Mali from 2006 to 2009, with two peace deals later in 2008 and 2009.

Read more: French support for the MNLA

From the beginning of the conflict, various fingers pointed at alleged French involvement in supporting the MNLA, a collaboration that, according to some French journalists, also involved Mauritania, a close partner in French counterterrorism efforts. While France’s potential involvement in encouraging the rebellion remains an open question, the governments (and secret services) under Nicolas Sarkozy and François Hollande saw the MNLA as potential allies against AQIM and in seeking the release of French hostages held at the time in the Sahara. This is in addition to the sympathy in some quarters in France for the cause of Tuareg independence that has lasted since the colonial era. Suspicions of French intentions grew after the liberation of Mali, when French forces interceded to help keep Malian forces away from the MNLA and its allies in Kidal for months, a time when elements of the MNLA aided French forces seeking to root out extremist militants in northern Mali. Read more.

This is one of the co-authors of the living analysis.

A labyrinth of armed groups (a battlefield perspective)

The fall of Libya’s dictator Gaddhafi also caused spill over violence which in effect unleashed the 2012 rebellion. The Tuareg, who had formerly fled Mali and served in Libya’s army, later returned to northern Mali fully armed after leaving their posts when NATO established a no-fly over zone. The Tuareg though are hardly united. Despite rebellions of Tuareg groups, their divisions should not be overlooked nor should they be seen as representative of northern Malians. Grouped by language in the 2009 Malian census, the main ethnic groups in the three northern regions are Tamasheq, Songhay and Peul. Tamasheq is the language of the Tuaregs and only in the region of Kidal are they the majority of about 90%. Sometimes called Kel Tamasheq (the people who speak Tamasheq) Tuaregs are further divided between clans and caste. Darker skinned people called eklan in Tamasheq (bella in Songhay) often viewed as descendants of slaves are far less supportive of Tuareg independence. During the 2012 rebellion it was reported that some slave descendants were recaptured by their former masters.

Read more: on the battling coalitions

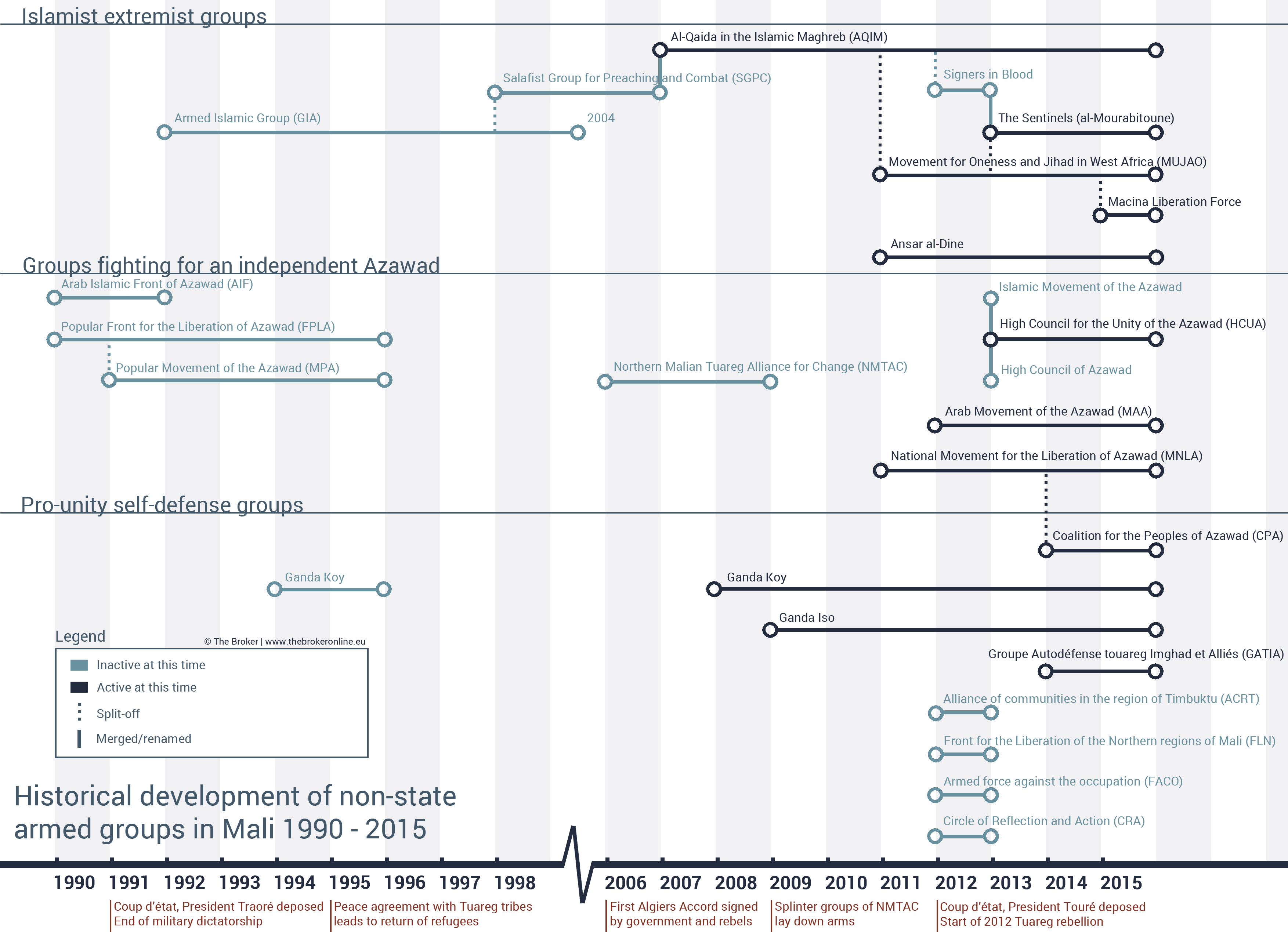

There are three main categories of armed groups present in northern Mali including: 1) separatist groups fighting for an independent Azawad, united under the Coordination of Azawad Movements (CMA); 2) pro-unity self-defence groups that claimed a seat at the peace talks as the more loosely affiliated Platform of Algiers (or the Platform); and 3) various Islamist extremist groups.

Image: Historical development of non-state armed groups in Mali 1990-2015. Click for a large version.

The CMA unites the National Azawad Liberation Movement (MNLA) with the High Council of the Azawad Unity (HCUA) and, a large part of the Arab Azawad Movement (MAA). In 2011, Ifoghas Tuareg leader Ibrahim ag Bahanga aimed to unite all the Tuareg clans under the MNLA. Initially succeeding, this later failed when another leader from the Ifoghas region, Iyad ag Ghali, created Ansar al-Dine in 2012. After the French invasion, ag Ghali’s deputy Alghabass ag Intalla formed the Islamic Movement of the Azawad (MIA), which later dissolved into the HCUA. The HCUA mainly represents the interests of the Kel Adagh clan to which both ag Ghali and ag Intalla belong. These Tuareg groups are mostly from the higher caste clans located in the Ifoghas mountain region. The MAA partly represents the interests of the Arab community in the region. Reportedly funded by Arab businessmen with ties to the trafficking business, it has split into a pro and anti-government camp with the Algerian peace talks.

The Platform’s more loosely tied pro-union coalition includes MAA members that see their future in the Malian state alongside the Coalition for the Azawad Peoples (CPA), the Imghad and Allies Tuareg Self-Defence Group (GATIA) and the Coalition of Movements and Patriotic Front of Resistance (CM-FPR). The CM-FPR coalition includes the following organizations: the Ganda Koy and Ganda Iso self-defence groups who represent the ‘black community’ of mainly Songhai and Peul speakers; the People’s Movement for protecting Azawad (MPSA) (also split off from the MAA) and; smaller self-defence militias. Tuaregs are represented by the CPA that split from the MNLA at the Algiers process and GATIA, which claims to represent the interests of lower caste clans.

The Islamist extremist groups include: Al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM); the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO), mainly composed of Tuareg militants; Ansar Al-Dine; the AQIM and MUJAO offshoot Al-Mourabitoune and; the Macina Liberation Front led by radical preacher Hamadoun Koufa from the northern Malian Peul community.

This social complexity in northern Mali can help shed some light on the various armed groups. United under the flags of the Coordination of Movements of Azawad (CMA), fighting for independence, or the pro-unity Platform of Algiers (click the icon to the left for more information) these battling coalitions are not heterogeneous groups. Rather they are hybrid formations with different aims. Rapid changes within and between the battling groups occurred during the conflict including the pro-unity Imghad and Allies Tuareg Self-Defence Group (GATIA) which consisted of Imghad Tuaregs that later joined the Songhay Ganda Koy and Ganda Iso militias and a faction of the Arab Movement of Azawad (MAA) to counter the CMA. Peul speakers (also called Fulani) have rejected Tuareg elite rule however many others have also dismissed the government and continue to reside within the spheres of influence of armed groups like MUJAO.

Motives and ambitions of armed groups are thus difficult to determine exactly. Coalitions have emerged to strengthen groups’ positions at peace talks or to perhaps avoid the terrorist blacklist. Groups act violently to acquire territory and influence which eventually causes the less violent groups to split off. This fluidity is reflected in the various extremist Islamist groups operating across borders in the region as well. For example, Al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) has had a series of leaders holding positions for a short time including Hassan Hattab, Nabil Sahraoui, Abderrazak “El Para” and currently Abdelmalek Droukdel, plus many other high-profile regional commanders such as Abdelhamid Abou Zaid, Mokhtar Belmokhtar and Abdelkrim, “the Tuareg”. Brigades within these organizations are often loyal to these leaders, which lead to new splits and new group formations.

Read more: Sahelian islamist groups in and outside of Mali

By 2006, Nigeria’s Boko Haram members were training in the Sahel alongside AQIM fighters. Cooperation continued until at least 2013 when a large contingent of Boko Haram fighters attended an AQIM training centre in the Timbuktu region in Mali. Ansar al-Dine received funding, logistical and military support from AQIM and later hosted members of Boko Haram in territory it controlled in Timbuktu region. Timbuktu villagers reported that Boko Haram militants lived and trained there while occupying abandoned government buildings. An Al-Qaida offshoot, the Movement of Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO), has also worked and trained alongside Boko Haram in Mali.

Boko Haram has now pledged allegiance to Islamic State (IS) and has renamed themselves Islamic State’s West African Province (ISWAP). Declaring allegiance to the group has brought notoriety and likely other benefits as well, but Al-Qaida and IS are increasingly at odds. In the relatively new group Al-Mourabitoun, a split emerged when one of its leaders Adnan Abu Walid al Sahrawi declared allegiance to IS, while its other leader Mokhtar Belmokhtar denied this IS allegiance and restated its loyalty to Ayman al Zawahiri and Al-Qaida. Additionally, Al-Mourabitoun has increasingly gained notoriety by its repeated attacks in Mali. Mokhtar Belmokhtar was targeted by a U.S. airstrike in Libya in June 2015 but survived according to an Al-Qaida statement.

It seems though that IS is spreading to other parts of the Sahel-Sahara area. In Algeria, the extremist Islamist splinter group Djound Al-Khilafa en Algerie (Soldiers of the Caliphate in Algeria) who was responsible for beheading a French tourist has pledged allegiance to Islamic State (IS). In the east of Libya, extremists who have returned from Iraq and Syria have seized the town of Derna and declared their support for IS. They also later captured Muammar al-Qadhafi’s hometown of Sirte. With the arrival of IS in Libya, the extremists trademark of filmed beheadings also came with them. These groups might be framing these statements to feed the already existing fear and negotiate for power. As in Iraq, Libya’s lack of stability and inclusive government creates fertile ground for extremism.

Negotiations for peace, stability and development (a political perspective)

In June 2013, the Malian government and the Tuareg separatist groups signed the Ouagadougou accord in the capital of the neighbouring country Burkina Faso. This was a preliminary accord that paved the way for new elections aimed to start ‘an inclusive dialogue to find a definitive solution to the crisis’ (Chapter 1, Article 2 of the accord) after a new government was elected. After this initial development however, the process was stalled as the newly elected government did not think it needed to make concessions to the rebels.

Read more: the Algiers Accord

The Algiers Accord was signed on 20 June 2015 read its full text here (in French). Read the latest UN Secretary-General’s report on the status of MINUSMA and peace process implementation here.

Consequently, the government was driven out of the Kidal region between November 2013 and May 2014, after which it committed to peace talks once again. After eight months of hard talks, this so-called Algiers process resulted in a ceasefire agreement with a final draft of a peace plan on 1 March 2015, resulting in the Algiers Accord. The preliminary agreement was then signed by the government and the loyalist coalition but the CMA decided not to sign. They committed two months later on 20 June after securing extra assurances on the representation of northern residents and the creation of a northern security force where armed groups will be integrated. The general challenge of balancing regional autonomy in northern Mali with a southern government intent on exercising its sovereignty still remains. In addition, critics of the accord say the agreement primarily reflects the wishes of the rebel groups and it remains unclear how it will have an impact of livelihoods at the grassroots level.

Read more: reflections on the peace process

Addressing the conflict over the institutional status of northern Mali has been a priority for the international community. While the focus on the political dialogue must continue, no solution will be viable until the nexus between criminality and violent extremism in the north is eliminated, and the links between rebel groups and transnational criminal networks are curtailed. Read more.

As inclusive as Mali’s national commission plans to be, its work is not perfectly cut out as of yet. Ultimately and given the porous borders between Mali, Niger, Algeria and Mauritania, disarmament, demobilization and reintegration efforts in Mali should be conducted in close coordination with those of its neighbors. And even though a peace agreement has been signed, the outcome of the DDR process will heavily depend on how well the different parties represented within the commission balance their respective interests while maintaining the spirit of the Algiers Accords. Read more.

Currently the main trend of decentralization in Mali is to give more power to the regions.This regionalization is mostly intended to resolve the political issue of the Tuaregs and northern Mali by setting up stronger regional political bodies able to enter into, and develop, political dialogue with the central government and its multilateral and bilateral funding partners. Decentralized bodies such as regional governments/assemblies, are still too far- remote to be able to address their basic livelihood needs. Read more.

In a political environment in which political alliances can be forged between any kind of groups, but only for a limited time, neither the state, the rebels nor the terrorists are capable of building a large coalition that would transcend social and religious divisions. The inability to govern northern Mali other than through local tribes has never been so obvious, both for the Malian government, which reproduces a political system born during the time of colonization, and for the international community, whose resources are stretched to the limit after several years of conflict in what is probably one of the world’s most inhospitable places for Western armies. Read more.

These are co-authors of the living analysis.

Trust between rebel leaders and the Malian state is still at a very low level though. President Keita was elected on a ‘strong man’ platform, one that advocated a military solution for the crisis. The aggressive GATIA self-defence group is also widely believed to be supported by the Malian government to circumvent the peace accords. Furthermore, even though the President promised to tackle corruption and poor governance in his election speech, less than a year later the World Bank, IMF, and EU temporarily froze millions of dollars in aid payments to Mali out of concerns over mismanagement of public funds. A problematic trend considering the state’s previous misuse of aid money where aid for the north was used to co-opt its elites into a clientelist system, which has now only contributed to today’s conflict and mistrust.

Read more: the political climate in Mali

When Malian voters overwhelmingly elected Ibrahim Boubacar Keita to the presidency in 2013, many in Mali and abroad felt that the veteran politician known as “IBK” had both the experience and the political legitimacy necessary to lead the country through its darkest period since independence. In the months that followed, however, the buoyant mood gave way to frustration. Read more.

President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta was elected on a popular platform of resistance to large concessions to the Tuareg rebels in Northern Mali. This does not provide a suitable platform for negotiations, but the peace process is also complicated by the fact that the most important armed actors like AQIM and MUJAO are not present at the negotiation table. Read more.

Many self-proclaimed tolerant Muslim leaders in Bamako cultivate a fear of Wahhabists and specifically those Wahhabists who are explicit about their non-political agenda and their active stance against militants in the north. We spoke with religious leaders in elite circles in Bamako in June 2014 and they spoke of Wahhabists being ‘Satanists’ or ‘jihadists’ and that ‘they try to take over our country’. Similar views were expressed in such statements, ‘We must get them, before they get us’ and, ‘They have arms, we must arm ourselves’. Read more.

These are co-authors of the living analysis. Read more about our living analysis here.

Ruling interests in the region (a geopolitical perspective)

Two years after the peace agreement was signed, continued commitment to the peace process and its successful implementation are Mali’s main challenges, but the region remains restless. Burkina Faso, Niger and Senegal face threats from violent Malian groups, violence in Libya and South Sudan continues, Niger, Chad, Nigeria, Cameroon and the Central African Republic struggle with Boko Haram, and Algeria and Tunisia are attempting to keep Libyan violence at bay. Such ongoing instability creates risks and opportunities for regional relations as countries try to protect their interests.

Video: at the General Assembly, Mali calls for a global UN approach to Sahel’s regional challenges

The involvement of neighbouring countries in the Malian conflict is strongly motivated by the fear of spill-over effects in the already unstable region. The Joint Sahel Force – FC-G5S or G5 – was created in June 2017 and started operating at the beginning of November. It consists of troops from Mali, Mauritania, Burkina Faso, Niger and Chad. The UN Security Council welcomed, but did not financially support, the G5, and, although the Security Council later declared that it would provide logistical and operational support to the force, uncertainty regarding its financing continues. The cost of the force was estimated at EUR 423 million in the first year, but France estimates that the force needs only EUR 260 million a year. Currently, it is financially supported by each G5 member, the EU and several individual member states, the US, and, surprisingly, Saudi Arabia (which contributed EUR 100 million) and the United Arab Emirates (which contributed EUR 30 million). However, these contributions do not cover the estimated cost of the force. The force not only faces financial obstacles, but the goal to have seven battalions fully trained and operational by March 2018 is very ambitious.

Read more: Algeria's diplomatic role

President Touré accused the Algerian president of failing to maintain control of his intelligence services, which Mali said were acting on their own in the Sahel and fuelling regional tensions. Sahelian governments also suspected that Algeria is seeking to dominate its neighbours by asserting control over counterterrorism operations and lucrative smuggling routes.In 2013, ECOWAS, France and the Sahelian countries questioned Algeria’s contributions to a negotiation process with the armed groups. In particular since the leader of Ansar al-Dine, Iyad Ag Ghali, is well known in Algeria and works closely with the Algerian intelligence services (DRS). Read more.

After eight months of hard talks the Algiers process resulted in a ceasefire agreement and the final draft of a peace plan on 1 March. The ‘Agreement for Peace and Reconciliation in Mali from the Algiers Process’ represents a compromise between the government in Bamako and the Tuareg and Arab rebel groups present in the negotiations. However, while the preliminary agreement has been signed by the Government-led coalition, the Coordination, representing the rebel groups present at the Algiers talks, decided after consultations with their home constituencies on 16 March not to sign the agreement. Read more.

The resurgence of Algeria as a power in a troubled region has been extensive. In Mali, it played a significant role during the French military operation Serval (2012-2014), even though it did not contribute any ground troops. In addition to opening its air space to the French, the Algerian military sealed its borders with Mali to prevent armed Islamist groups from withdrawing and cut off their sources of funding. The country also played an important mediation role in the inter-Malian dialogue between the Malian government and the political-military movements of Northern Mali. In Libya, Algiers leveraged its diplomatic connections to facilitate dialogue between the disagreeing Libyan parties, while in Tunisia, it pressed for a dialogue between Nidaa Tounes and the Islamists of Ennahda. But even though the country clearly has ambitions as a regional power it will need to capitalize on its assets before such ambitions can become an enduring reality. Read more.

These are co-authors of the living analysis.

From an international perspective, Western powers refer to what they call the ‘arc of instability’, of which the Sahelian and Maghreb regions constitute a large part. European states hope to route the current exodus of migrants traveling through these regions towards Europe via its ancient desert trading routes. Western power security motives go beyond migration, and may be related to unexploited natural resources and political power struggles. Beyond the Western powers, China’s decision to deploy troops to both Mali and South Sudan can be seen as a sign of its increasing reliance on African natural resources.

Read more: Geopolitical currents in the region

In neighbouring Libya, general Khalifa Haftar – supposedly with the support of Algeria – initiated an armed offensive against Islamist militias in May 2014. The fall of Muammar Gaddafi in 2011 not only destabilized the Algerian government but weakened its control when the Islamic Maghreb splinter group attacked the In Amenas gas facility near the Libyan border in January 2013. Read more.

Gaddafi was undoubtedly a ruthless dictator and at times a source of regional and global instability who used his oil wealth to support all kinds of rebel movements around the world; from trafficking weapons to the Irish Republican Army (IRA) to establishing training camps in Libya for people like Liberia’s Charles Taylor and Sierra Leone’s Foday Sankoh, and going to war against Chad to claim the Aozou Strip. However, Gaddafi’s Libya was also a bastion of stability in a volatile region. Read more.

Without an external intervention, a Libyan unity government that is dependent on the support of the country’s non-state armed actors would have to stabilize the country, disarming these same militias or choosing to integrate them into the National Army with the risks that this entails. (…)Until this is done, the Libyan state will not be able to effectively commit to regional cooperation on security or related issues like migration and trafficking. So while the current progress towards a unity government is a positive development, it will take time and commitment before much needed stability and development in Libya will have an impact on the region. Read more.

Governments in the region have been accused of alternately aiding and impeding peacebuilding efforts, with varying degrees of evidence. At various times during and after the occupation of northern Mali, MNLA delegations and representatives were based in Ouagadougou and the Mauritanian capital of Nouakchott; Ansar al-Dine leaders could be found at various times in Ouagadougou and Algeria, while Niger hosted the loyalist Tuareg military commander El Hajj Gamou and his troops until after the French intervention. Read more.

President Déby gets away with it mainly because of France’s and United States’ counterterrorism efforts, general economic and security interests and military means that has accumulated through oil-exploitation. Major powers predict regional chaos and loss of control in the region when Déby goes out of power. Yet internal chaos, injustice and generally poor governance is a daily reality for the approximately 11.5 million inhabitants of Chad. Read more.

The framing of the LRA as an absent or spent force by the Congolese government and army can be explained by the fact that it has much more important threats to its territory, but particularly by its relation with Uganda: during the earlier Congo wars, Uganda had been occupying parts of the DRC and exploiting natural resources. By framing the LRA as absent, the Congolese government and army wanted Uganda to leave its territory. Read more.

These are co-authors of the living analysis.

Fighting extremism, building states? (a human security perspective)

Creating conditions to allow Malians to look after their own situation should be the primary strategy. Without creating such conditions, repressive anti-terrorism strategies can lead to further radicalization, especially among young people that are increasingly faced with rapid population growth and a lack of economic opportunities, particularly in the north. The challenge is to come up with solutions that go beyond the short-term political commitment and head towards sustainable change. This means providing Malians with a stable income, food, equal access to services like education and healthcare and a transparent, accountable system of political representation.

Read more: going beyond the state in the analysis of conflicts

Short-term and overly technical perspectives are currently institutionalized among the approaches of many international actors while a need for a different political, local, regional and integrated approach currently exists. In particular, local, social and cultural perspectives on the conflict should be included in intervention planning more frequently. In a study by The Broker, international actors’ context analysis methodologies revealed that the local and regional levels of analysis and planning are often overlooked, while a cultural perspective that views a context through ‘local’ eyes is often lacking.

Any international interference however requires a long-term development strategy and a political strategy. The Malian conflict should be approached from a regional perspective that critically analyses its local and regional political economy. The current volatility of Libya for instance offers Islamist extremist groups new opportunities to root themselves in local communities. Fluid patterns where extremist Islamist groups and criminal networks that can easily relocate along transboundary networks in the Sahel while creating new hotbeds of conflict along the way will eventually undermine local military interventions. This ‘waterbed effect’ can only be countered by regional action that is rooted in a ‘political’ approach where local populations are engaged and their needs and concerns are considered. Decentralization to the local level, not only district level but also the community level where the population feels most represented and should be part of the approach.

Read more: youth unemployment, crime and terrorism

There is a link between unemployment especially among youth and insecurity in Mali. Faced with few remaining economic alternatives, many young people from the northern city of Timbuktu are opting for criminal and radical groups for their survival and livelihoods. Some groups seem to have been well rooted in these communities for over a decade. They strike at the most vulnerable moment, recruit youngsters and lure them with short-term cash or goodies. Read more.

The government should be thinking of creating an enabling environment which will promote youth employment, instead of focusing on direct job creation. Such an environment should involve tax exemption for startups, and obliging financial institutions to only apply minimal interest rates on bank loans taken out by young entrepreneurs. In addition central government should also accelerate the process of decentralization and consider local governments as a main ally in creating an enabling environment for youth employment. This has not yet happened. Read more.

These are two of the co-authors of the living analysis.

Success in restoring long-term stability and security for the people of Mali and the Sahel as a whole depends on the competing interests that underline the efforts to resolve the conflict. The Malian government’s historically strong regional orientation, expressed through its membership of ECOWAS, the African Union, and the African Development Bank, should provide a firm basis for working toward such a solution. Building on and strengthening such fundamental principles should be leading in the reorientation of regional cooperation and stability, and should form a solid basis for the outward orientation and economic and political cooperation with international partners.

Read more: how to work regionally?

In the Sahel and the Sahara, international strategies attempt to address humanitarian emergencies, security, development and governance in an integrated manner. Implicitly, these strategies are based on regional and decades-long planning. But in practice they are much more short term. There are six possible frameworks within which regional action can take place:

- In the Sahel, territories with no dedicated or adequate regional organizations, international agreements or Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) have to be signed (for instance, if ECOWAS decides to engage with Sahel-wide issues together with Maghrebian states).

- Building the national base of regional policy pillars. So far, available financial resources are mostly allocated at national level.

- Strengthening cooperation between like-minded groups of states to set up joint initiatives like patrols along common borders and infrastructure programmes. A recent example is the G5 for security and development, comprising Mauritania, Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger and Chad.

- Initiating cross-border cluster activities for local authorities, community leaders, businesses, religious and nomadic groups working on both sides of the border to enable them to live their lives without being overloaded by exaggerated constraints created by states.

- Transnational action covering territories regardless of state boundaries to deal with issues like regional environmental challenges, organized crime and illicit trafficking, satellite information-sharing, cross-Sahel migration flows, financial flows, cultural and religious relations, or cyber security. This requires a comprehensive understanding of transnational phenomena, a wide geographical coverage and the ability to combine those assets that engage specific partners at a national level.

- Operating through networks of expertise and experience, including civil society organizations (CSOs) and private companies. An example is Eau-Vive, an NGO registered in France and operating in over a dozen countries in West Africa with mostly African staff, which is plugged into a variety of CSO networks and recently launched launched an international federation.

This is one of the co-authors of the living analysis.

Ongoing process

A living analysis means that Sahel Watch will be constantly updated to be able to ‘watch’ the ongoing dynamics and their impact in the region. The perspectives we have identified so far are not fully exhaustive and we will constantly look for different ones and blind spots in current analyses.

We hope to contribute to more comprehensive policies and practices. This long read is therefore relevant for anybody who is engaged in improving the human security situation in Mali, and not just governments, international organizations and academics, but also local people and communities.

This analysis was co-written by many authors, please click on the icon to the left to see who contributed.

On 7 February, the G5 leaders appealed for more funds for anti-jihadist force after a summit in the Niger capital of Niame.

On 1 Februari, a report published by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and MINUSMA expressed concerns over human rights violations, it reports more than 600 human rights violations between January 2016 and June 2017.

On 30 January, Soumaïla Cissé, the leader of the opposition in Mali, called for respect of the electoral procedures in response to president IBK threatening to cancel funds for opposing parties.

On 29 January, Security Minister Salif Traore said the government’s priority is to stabilize central Mali before the elections in April.

On 24 January, the UN Security Council threatened to use sanctions against parties that obstruct or delay the implementation of the peace agreement.

On 22 January, the UN peacekeeping chief Jean-Pierre Lacroix urged the Malian government to “create conditions that would lead to elections” and a day later he told the Security Council that time had come to reassess MINUSMA’s assumptions and layout.

On 16 January, president Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta threatened to cut the budget for opposition leader Soumaïla Cissé because he criticized the government.

On 12 January, the Malian government accepted a new law that grants more legal protection to Human Rights defenders, it was welcomed by different human rights defending organizations that indicate that measures should be taken to ensure effective implementation.

On 10 January, around a 100 people demonstrated against French military operations in Bamako and the police used tear gas to disperse the crowds.

On 10 January, a regional bank official and the head of an African tech initiative announced their presidential bids for the elections in July. Two other candidates had announced their bids earlier: former Malian army general Moussa Sinko Coulibaly and the mayor of Sikasso, Kalifa Sanogo. IBK has not yet confirmed, but is widely expected to join the race.

On 16 January, Ahmed Boutache, president of the follow-up committee for the peace agreement, said implementation of the peace agreement was complicated by the the question of rebel disarmament.

On 31 December, president Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta appointed the thirty-six new ministers of the government after their predecessors had resigned with the Prime Minister Abdoulaye Idrissa Maïga that now runs as presidential candidate.

Footnotes

1. Zwarts, L, Beukering, P. van, Kone, B. & Wymenga, E. (2005) The Niger, a lifeline: Effective water management in the Upper Niger Basin, RIZA, IVM, Wetlands International & A&W.

2. Dijk, H. van & De Bruijn (1995), Pastoralists, Chiefs and Bureaucrats: A Grazing Scheme in Dryland Central Mali. In: Local Resource Management in Africa, New York: Wiley.

3. Retaillé, D. & Walther, O. (2011), Spaces of uncertainty: A model of mobile space in the Sahel Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 32, 85–101.

4. Bergamaschi, I. (2008), Mali: patterns and limits of donor-driven ownership. In Whitfield, L. (ed.), The politics of aid. African strategies for dealing with donors, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 221.