The fifth session in a series on the decolonisation of aid: So much has been discussed up to this point; so many valuable insights, arguments and viewpoints shared; and throughout many of the conversations of the last couple of months the role of the donor has already been touched upon. In pursuit of meaningful decolonisation of the development sector, however, the role of the donor warrants some more in-depth discussion. “It is,” as The Broker’s moderator Kiza Magendane argues, “a vital precondition for this entire endeavour.” To critically reflect on the role and responsibilities of the donor on the road towards a decolonised system, two speakers will take the stage: Smruti Patel – founder and director of the Global Mentoring Initiative (GMI) and founder and member of the Alliance for Empowering Partnership (A4EP) – and Dirk-Jan Koch, Professor of International Trade & Development Cooperation at the Radboud University Nijmegen as well as Chief Science Officer for the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs (speaking in a personal capacity).

Beyond the intellectual?

Before the two experts take to the virtual stage, Kiza Magendane poses the question that has been haunting organisers, speakers and audience from the very start: What are we actually realising with these discussions? Is this simply an interesting intellectual debate or do we have impact beyond that? To Prof. Dorothea Hilhorst, from the International Institute for Social Studies (ISS), who has been involved in the sessions from the very beginning, the idea of this series being an intellectual exercise is not necessarily a problem. “It is very important,” she argues, “that people from practice also engage in intellectual questions from time to time.” For Hilhorst, the real value of these sessions is not found in immediate, tangible change. “What I find most important is that it helps people reflect on their day-to-day practice.” Her hope is that, in the weeks and months following these discussions, participants’ thought processes will continue and their views and ideas about ‘what was always considered normal’ may change. In other words, Hilhorst says, “these sessions, I hope, can act as a sort of ‘mental floss’, opening people’s minds to the possibilities of change.”

Turning now to the heart of the matter – the role of the donor in decolonisation – Hilhorst poses some critical questions to get the discussion going: Are donors engaged in the debate at all? And are they merely following, or could they even lead the debate? Additionally, what is meant by the term donor? “The way in which we understand the concept today”, she argues, “is limited to countries that finance aid and development.” For Hilhorst, however, the relevance of the debate goes way beyond that. “You could say that all INGOs are donors. They all avail of money which they decide to give or not to give, and they too subcontract others to do the work.” With that, the floor is open to the two speakers – Smruti Patel and Dirk-Jan Koch – each of whom shares their thoughts on Hilhorst’s and other questions.

The donor contradiction

Opening her speech, Smruti Patel immediately touches upon an issue that has been raised in previous sessions as well. When talking about the donor, it is assumed this is the actor who ‘owns the money.’ However, Patel argues in agreement with earlier speakers – Hugo Slim and Tulika Srivastava – the money is public money. “It is money belonging to the affected populations because we are raising it in their name.” She is raised the question how are they showing up and expressing solidarity at country level. Indeed, Prof. Dirk-Jan Koch agrees that the money is meant for solidarity and belongs to the communities we seek to support. Yet, at the same time, he notes, it also belongs to the people – the taxpayers – who give the money. Koch argues that in this conversation the term ‘mutual accountability’ is useful. As the money is given to spend on poverty alleviation and supporting the most marginalised, ‘downward accountability’ – i.e. donors being accountable to their beneficiaries – is of vital importance. “At the same time,” Koch argues, “I understand that those who have been providing this funding from their own pocket would like to know what has happened.” Inclusive development policy and funding means holding both sides accountable for meeting agreed targets and sticking to the jointly made plans. Based on her experience, Patel is somewhat sceptical about the notion of mutual accountability because, as she puts it, “it is usually more about account-ability.” Presently, accountability is about adequate bookkeeping and showing that targets are being met, while meaningful, decolonised accountability should be about “involving the populations in making decisions on the projects and programmes that affect them.”

In addition to questioning current accountability mechanisms and the ‘ownership’ of money in aid, Patel wonders just how ‘fit’ present-day donors are to deal with current and future challenges in a way that best matches the needs of those people we are seeking to support. “The way the system is organised today,” Patel argues in line with the previous sessions, “is very colonial, with colonial mindsets.” Power and control are now located with the Northern donors. Yet, Patel notes that donors “are doing a great job in putting some key issues at the centre [of development practice]: For example, gender equity, inclusion, diversity.” Thus, a contradiction becomes visible: “On the one hand [donors] are providing funding to make sure there is gender equity, there is inclusion and we [development actors] can be held accountable,” Patel explains. “Yet, on the other hand, the system itself is not accountable, is not inclusive, it is very patriarchal and […] marked by a trust deficit.” Racism, prejudice, injustice – all of these are currently coming into play when funds are being distributed. To get rid of this contradiction and decolonise the system, Patel feels donors have an important role to play. In addition to putting on the agenda and prioritising the aforementioned issues of gender equity and inclusion, they can similarly encourage organisations to adopt explicitly decolonised approaches – a view that is shared by the second speaker.

Donors are people

Ten years ago, Koch became the country director in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) for a large international peacebuilding organisation. With a staff of approximately 100 people – 95% of whom were Congolese and the other 5% white and mostly in positions of power – the organisation was doing very important work, such as providing human rights training to the Congolese army. It was, however, in a lot of trouble. There was a serious problem of corruption, the organisation was failing its audits and, consequently, donors were demanding their funds back. There was, in short, a strong trust deficit – and not without reason. Koch’s assignment was to ‘clean the house’; ensuring the accounts were put in order, getting rid of corrupt staff members and rebuilding trust with the donors. Especially in this last task, the ‘colonial’ nature of the current system became apparent to Koch: “When donors saw a white face, especially one that spoke their language, I saw that their trust improved,” he narrates. “To me it was an example that, indeed, mindsets are still full of prejudices in the sector.” Now, ten years later, Koch shares his reflections on these experiences: “Did I contribute to reducing corruption, or did I actually contribute to [maintaining] it? I had privileges, access to a car and a house that local colleagues did not have. In this way, I was introducing more inequality to the system and perhaps [feeding] the scheming that comes with it.” Presently, Koch does not have an answer to these questions, but they do underline what Patel also pointed out: At present, the humanitarian and development systems are regularly occupied by people who are the products of and perpetuate the colonial mindsets and ‘rules of the game’. When seeking to change these rules and mindsets, we must, therefore, look closely at people and ask the questions Patel also posed: “Are the people in the system open-minded? Do they have the open heart and the open will to change? How can we make sure they do not [hold] negative narratives about local actors? […] And how can we tackle their [colonial] trust deficits?”

Decolonising donors

At the very start of this session, Prof. Hilhorst, in addition to questioning what we mean by ‘the donor’, asked whether donors are following or could even be leading the current debate. In his presentation, colleague Koch sketches some pathways for donors that would allow them to ‘become leaders in the debate’. At present, the funding system – and the donors within that system – is perpetuating the colonial power imbalances Patel also mentioned. The funding and aid systems we have today, however, were established for a reason. Many of the poorest countries in the world – the ones that stand to benefit most from international aid – are also faced with very poor governance structures. In these nations, where accountability is lacking, where governments cannot be relied upon to spend aid funds on the people that need it, a parallel system had to be set up. Decolonisation does not mean abolishing this whole system and getting rid of all the intermediary NGOs. The current system and the relationships that have been built between donors, (I)NGOs, local organisations and communities have many positive aspects and effects. Yet, while this system may deliver more support and accountability to populations in the global South than their respective governments could, Koch argues it is not enough. The system needs a thorough transformation and for donors to take the lead in this process, they must step up their game in three areas:

- First, donors have a lot to gain with respect to their supervision policies. 14 years ago Koch analysed the composition of supervisory boards of international NGOs and found that only 6 per cent of board members were non-White. Preparing his presentation for this session, he checked again the websites of a few Dutch international NGOs and was very disappointed: Little progress has been made. “And I do blame the donors for that,” Koch states, “because they have never asked for [diversity on supervisory boards] in all their guidelines.” But the blame does not lie with the donors alone. “We all have a role to play,” he continues and calls into action KUNO – one of the organisations hosting this session: “Why don’t we make a research project out of this?” Koch suggests. “And make a ranking of which INGO is doing best in this respect?”

- The second area Koch addresses relates to donors’ reactive stance towards advertisement campaigns of their grantees. Despite much critique against the adverts of aid NGOs displaying poor people in their most vulnerable state to acquire funding, the ‘guilt- and pity-triggering’ images are still being used today. Improvements are visible, not in the least because organisations like Partos have set up, with their members, a code of conduct that states organisations should select images and messages on the basis of ‘Respect for the human dignity of the people involved’. Donors, however, have taken a back-seat in this endeavour and left NGOs to auto-regulate themselves. According to Koch, donors have a responsibility to “demand that all advertisements by their grantees are not contributing to the ‘White Saviour Syndrome’”. And to Partos – the second organisation hosting this session: “I think you should toughen your guidelines in this respect too.”

- A last element in which Koch feels donors should step up their game is related to personnel policies. Many donors, including the Dutch government, do not have any criteria with regards to the diversity of staff of their grantees. Whether local staff is supported to grow into the position of country director, or whether all positions of power continue to be held by ‘Northern’ staff – the donor does not ask nor seem to care. To conclude this third point, Koch now calls to action all participants: “I know you lobby the government lots, especially on the funding schemes. So why don’t you lobby them on this aspect as well? And ask that empowering practices with respect to local personnel are rewarded in [the government’s] next subsidy scheme?”

Capturing (de)colonisation

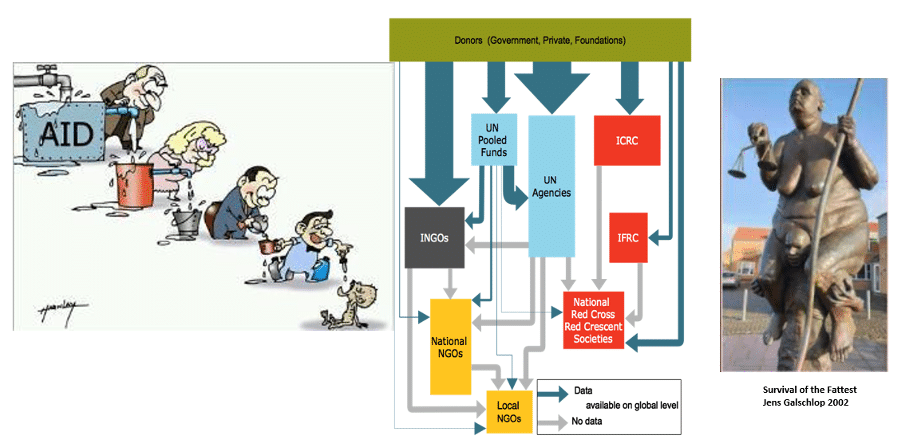

Throughout this webinar series on the ‘Decolonisation of Aid’, we invite the two keynote speakers to share an image that illustrates their analysis of the (de)colonisation of international aid.

Smruti Patel presents three images, all shedding light on the power imbalances in the current funding system, that she hopes ‘bring discomfort’. The first image shows painfully clear the way in which current aid funding is flowing: Along the road – from the white, powerful, male-dominated rich countries down to the most marginalised – much of the funds are being siphoned off, eventually leaving little to spare for those who really need it. The second image, presents the ‘formal’ side of the story, showing clearly the inequity of the current aid system on organisational level. Finally, the third picture – a 3.5 metre tall bronze sculpture titled ‘Survival of the fattest’, depicting a fat woman from the west, sitting on the shoulders of a starved African boy – signifies the ongoing unequal distribution of resources in the development sector. Still, most of the funding goes to the big organisations from the global North, while local actors – those who are doing the heavy lifting – are receiving only a small percentage of the money and resources going around in the system.

Dirk-Jan Koch shows participants a video-still of advertisement by an aid NGO. For him, it shows clearly the result of donors giving their grantees free reign in their advertisement campaigns. “There are still agencies that try to mobilise funding by appealing to the ‘White saviour syndrome.” Koch argues that donors should take their responsibility and set criteria to their grantees to use ads that are empowering rather than falling back onto old colonial stereotypes.

An empty shell?

Koch ends his presentation on a somewhat controversial note – especially considering that many NGO representatives in the audience are very protective of their autonomy. “Donors have not imposed enough rules,” he states. “They have left NGOs free to organise their supervisory boards, their advertisements and personnel policies, […] result[ing] in a largely regressive system in which a white gaze still prevails.” In Koch’s view, donors should put a premium on empowering people of colour because without such measures, he argues, “this won’t happen, or way too slowly.” As expected, this view does not enjoy full support from all participants. Among them is Prof. Hilhorst who – although agreeing with Koch on most points – expresses her worry that if this push from the donors is not complemented with a push from ‘below’ and driven by local actors, the donor’s push “becomes a very empty shell”. Involving people from the countries where humanitarians work is, for Hilhorst, a precondition for formulating guidelines that will generate change towards decolonisation.

In addition, one can question how meaningful and credible a push for decolonisation from the side of the donors is, if their own institutions are not living up to the criteria Koch suggests they put to their grantees. Are donors themselves paying enough attention to their hiring practices, diversity policies and internal accountability procedures? As an example of where donors still have a lot to gain internally, Hilhorst refers to her past experiences with embassies. “I have felt almost ashamed,” she shares, “when I visited Dutch embassies and found out that the national staff, [who] are so knowledgeable, [who] have been there for twenty or more years, and who know everything that is going on, are still in a very marginal position when it comes to decision-making.” In this regard, Patel, Koch, Hilhorst and many of the participants – as apparent from their contributions to the online chat – are very much on the same page. Donors too, need to take a hard look in the mirror and change their internal policies and practices. One suggestion from participants was welcomed with open arms: the creation of a capacity building programme for donors, training the people in these institutions to be aware of and more adequately address internal power imbalances.

Hilhorst’s ‘empty shell’ critique with regards to a top-down push of donors for decolonisation has also has been expressed with regards to other aspects of donor policy and practice, among which is the concept of ‘localisation’. Localisation can be seen as a response to widespread concern about the fact that so much funds are ‘lost’ along the way from donor to local communities (see also Patel’s images in ‘Capturing (de)colonisation’) and, most importantly, about the top-down, Northern-led organisation of aid. Localisation is seen as a way to ‘shift the power’, which, for donors, means to allocate resources, not to big INGOs in the North but rather to actors in the global South. As Patel explains, however, in practice the promise of ‘shifting the power’ often turns out to be an empty shell: “Donors have been talking about how important civil society is to a country, to a society. Yet, what we see is that the donors’ money is shrinking the space for local civil society because they are putting more and more resources into big INGOs who are expanding their bases in the South.” A similar sentiment was recently echoed in an open letter by over 140 Southern CSOs directed at donor institutions. They argue that, while the intentions behind and the principles of ‘localisation’ sound great, “what happens in practice is that these efforts only serve to reinforce the power dynamic at play, and ultimately to close the space for domestic civil society. […] All of this serves to weaken us locally. It keeps us in a master/servant relationship continuously begging for grants from your institutions, while we remain bereft of core funding ourselves. This is not what we need or want”.

For Patel there is opportunity to improve the situation and tap into the potential that the localisation agenda holds. The crux, for her, lies in open communication, listening, and building local relationships. “Have annual direct consultations with local organisations. Speak to them directly. Do not look down on them. Do that, and you will get the direct input that you need.” As both Patel and Hilhorst argue, learning from local actors and supporting them rather than taking the lead is not only a moral imperative; it is an approach that will greatly benefit the communities we seek to support. Because, as Hilhorst puts it, these local actors have crucial capacities that go beyond the bureaucratic capacities we often think of: “Knowing what is going on, finding your way, knowing the local languages, being able to talk to local communities – we [should] see those as the most crucial capacities out there.” Beyond working with local implementing organisations or communities, moreover, it is equally important to build relationships with and strengthen the capacity of local social institutions. “Religious institutions, local authorities – they are at the end of day the social safety nets […] for vulnerable populations,” Hilhorst points out. “It is of vital importance to invest in those relationships, to work with these [institutions] and do as much as possible to empower them.”

The future starts tomorrow

To conclude this (for now final) session in the series, moderator Magendane invites the speakers to briefly look ahead. With the rise of new donors, what can we expect on our journey towards a new, decolonised system? In reply, Koch paints a rather pessimistic image, expressing his worry about accountability, especially towards the effected populations. “Despite all their weaknesses, the Netherlands, Sweden, and other progressive donors do try to make sure local accountability systems […] are strengthened,” he says. With the rise of China and other less democratic nations as donors, however, such accountability systems are unlikely to be maintained. In addition to this worry, Koch also shares an important opportunity he sees for improvement. “The donors have been too passive,” Koch argues, “and [they] have not imposed enough rules.” According to Koch, in the future, “donors can, and have to be, a driver of decolonisation.” And they can do this by putting a premium on NGO programming, approaches, and activities that actively work towards decolonisation and meaningful shifts in power to local actors. “Doing nothing leads to an entrenchment of the system. The change is happening, but it is happening way too slowly.”

Participants to this last session seem to be in strong agreement on this last point: Their contributions in the chat reflect a great impatience for development actors and donors to act now. While sharing this sense of urgency, Hilhorst also imparts a final piece of wisdom to conclude this series. Yes, it is of utmost importance to decolonise and shift the power, she agrees. “But we have to be extremely careful in [our quest for] decolonisation and [ensure] that it does not lead to a situation in which we say ‘hands off, let people manage their own affairs, they do not need us anymore’.” It has been said in all foregoing sessions and cannot be stressed enough: we must prevent throwing away the baby with the bathwater. We must work towards a system in which we get rid of the colonial and save all the good that humanitarian and development interventions are bringing. The key, Hilhorst argues, is a global politics of international solidarity. How do we realise this? What does it entail? “I think that is another series of debates,” Hilhorst concludes. “A series that we have to start tomorrow.”