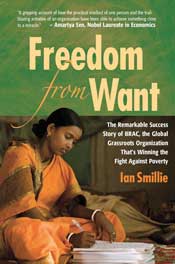

Freedom from Want: The Remarkable Success Story of BRAC, the Global Grassroots Organization That’s Winning the Fight Against Poverty, by Ian Smillie. Kumarian Press, 2009.

A review by Annette Jansen.

One wonders if a book that has been showered with praise by Nobel laureate Amartya Sen, former Irish president and High Commissioner for Human Rights Mary Robinson and former US president Bill Clinton needs to be reviewed again. Yet this acclaim may well be an expression of relief from a sector that has been the target of much scepticism and is hungry for some positive news. Ian Smillie’s Freedom from Want delivers that and more. Its tone and style inspire hope in the reader.

The book tells the captivating story of the Bangladeshi NGO BRAC (Building Resources Across Communities). Founded in 1972 by Fazle Hasan Abed, BRAC now has at least 57,000 branches in countries such as Uganda, Afghanistan and Pakistan. Freedom from Want is an account of the organization, which through trial and error and a high dose of perseverance discovered what Smillie calls ‘the fallacies in standard approaches to community development’.

Already in the early 1970s, BRAC realized that development was not about ‘getting bigger’, but about ‘how to make things different’, and how to change the patterns of power distribution that keep the poor poor. At a time when ‘gender’ was anything but a buzzword, BRAC decided to focus on the economic empowerment of women. It did so by launching, in 1975, a sustainable agriculture project based on poultry farming. By 1992, the project involved 1.9 million women, and had managed to establish commercial and social linkages that connected the local activities to the wider national economy, and introduced women to the experience of making real profits.

The poultry project story reveals another key ingredient of the BRAC approach: trial and error. After the failure of a large-scale project in Sulla, Bangladesh, BRAC realized that, in Smillie’s words, ‘the constructive dealing with error is much more important than reliable adherence to an action plan’. Start small scale, conduct research, test, improve, retest and only then scale up. In Abed’s words, ‘small is beautiful, but big is necessary’.

But BRAC did not only invest in its projects. ‘Development is not about buildings, it is about what goes on inside buildings, and inside the heads of the people in the buildings’, Smillie writes. BRAC discovered the importance of investing in people. Instead of bringing people in from abroad, BRAC recruited women from the villages and trained them to work as health advisers, teachers or silk producers. Realizing that ‘the best way to keep the best staff in absence of large salaries was to ensure the greatest satisfaction possible’, they sent promising young staff to obtain a masters degrees or PhDs at the world’s top universities. BRAC changed the lives of many people, not least those of its founders. It is these personal stories that make this book such a fulfilling read.

So is there anything negative to say about the book? In his closing chapter, Smillie suddenly starts bashing the militarization of aid, which seems somewhat out of place in a book that refers so little to this problem, and at a time when donors embrace an integrated approach to security and development. Similarly unexpected, Smillie then begins singing a song of praise for human rights, stating, ‘Rights, including legal rights, children’s rights, and rights for women and for men, were the cornerstones of long-term development’. This may cause the reader to wrongly conclude that NGOs are correct to mobilize people to demand their rights. What this book shows instead is that, although human rights ‘conscientization’ is important to raise people’s awareness and boost their confidence, real change is about building different power structures that link the poor to the wider world of economic opportunities. BRAC’s country director in Uganda remarks that microcredit is not a human right, but can, if properly used, become a vehicle for attaining human rights – thus reversing the often heard logic that ‘rights precede development’.