Terrorism watchers, particularly those in the Sahel region, tend to divide into two camps. First, there are those that see the emergence of terrorism in Africa to be a relative recent phenomenon that has come to prominence only in the last decade with the affiliation of AQIM and its various iterations to international terrorist movements. In contrast, the second camp argues that ‘Africa is the continent most affected by domestic or sub-national terrorism’ in which, in a hangover from decolonization, armed groups with political motives enact acts of violence against non-military targets intended to provoke terror. Regardless of which camp you might subscribe to, the Sahel governments in the region have never been more concerned about the fight against terror.

In a recent trip to the region, national authorities described being squeezed from all sides. Not only are the Sahel-based terrorist groups splintering into an impossible to follow myriad of factions with murky intentions, Sahel states are also dealing with the increasing virulence and encroachment of Boko Haram and the influence of ISIS across the Maghreb and Sinai. Whether these trends are causes or effects, governments are seeing that the nature of terrorism in the region is fundamentally changing, fragmenting and widening both in form and in geographical focus. Some interlocutors have described terrorism in the Sahel as now having two faces: the internationally targeted terrorist groups that have been prominent in recent years, where terrorist acts have been focused on international agendas, and with predominantly western and symbolic targets; and the steadily growing domestic terrorism, which particularly in 2015 is increasingly looking like a low-level insurgency.

A broadening base and scope

In Mali, terrorist groups are becoming increasingly more organized in to smaller groups as based on their shared language and cultural background and ethnicity, with notably similar characteristics to Nigeria’s insurgent terrorist group, Boko Haram. Tense ethnic relations and poor living standards are untangling and just in time for one of the most fertile periods of terrorist recruitment. Local populations and especially youth are joining terrorist groups (e.g. DAESH, MUJAO, Ansar Eddine, AQIM) in unprecedented numbers.

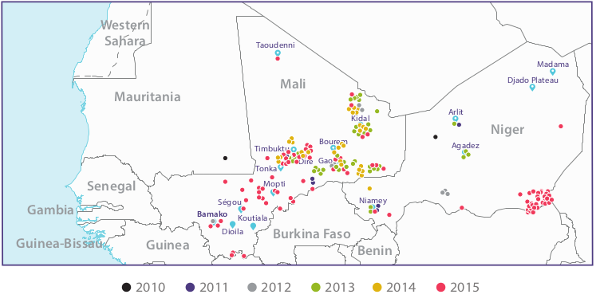

Image: Terrorist attacks in Mali and Niger 2010 – 2015. Source: author.

The year 2015 has seen a significant increase in Al Qaeda-linked attacks as compared to 2014.There is even evidence as shown in the map above of a strategic reorientation towards the southern part of Mali. There have been over 30 attacks in the country’s south in comparison to zero in the previous year, including two major attacks in Bamako. This includes many attacks by the Macina Liberation Movement, the front group of Ansar Dine. It also includes two major attacks in the country’s capital of Bamako by Al Murabitoon, which has since merged (back) into AQIM.

Some of the experts I interviewed attributed this increase to new agendas, while others speculated this is part of a strategy by the existing groups to divide the attentions of international and national security forces from the north of the country. In either characterization, the result has been greater insecurity and a further stretching of the already gossamer-thin capacity of state security institutions. Political will is essential in making an impact against this proliferating challenge, but the Malian government is already torn between diverging priorities, including the implementation of the peace accords. There is arguably neither the attention nor the budget to have a real impact in the security sector.

While Mali remains the epicentre of insecurity, there are reasons for concern about the wider Sahel region where the reverberations are acutely felt. In Niger, fundamentalist Islam is gaining potency in the country, both in society and in politics, which has been highlighted as a dangerous trend. While these supporters of fundamentalist interpretation of Islam are not violent for the moment, there is a general sense that Niger is a tinderbox and that continued governance or development failures will result in further radicalization of the population as the appeal of religious fundamentalism was widely attributed to poverty, inequality and lack of government service deliveries, particularly in terms of secular education. The same three features are offered as reasons for why terrorist groups may prove more successful in recruiting and gaining legitimacy with local populations. With controversy already growing around the Presidential elections planned for 2016, and the international community diverted by the challenge of growing illicit migration, there are many reasons to have concern about Niger’s future trajectory and stability.

Evolving responses mismatched to the threat

Despite a growing awareness of the changing nature of the threat of terrorism, which is resulting in a higher level of prioritization on the part of national governments in the Sahel and Maghreb, questions of counter-terrorism at the international level are being increasingly overshadowed by the issue of illicit migration, which preoccupies the conversations and concerns of the European and international organizations. There has been a sudden growth in the number of projects focused on this topic, and terrorism and security-related programmes have been partially re-orientated to also address clandestine migration and human trafficking which is somewhat detracting from a focus on terrorism directly. The majority of these interventions continue to be in the area of capacity building for security and justice institutions, and thus may not be a significant programmatic diversion, yet it does affect political prioritization. Fundamentally however, many of these challenges (terrorism, fundamentalism, illicit migration, and criminalization more broadly) have the same roots and these security-first approaches struggle to have impact.

In responding to terrorism’s newest (or arguably its historic) face, the global rhetoric on the need to counter violent extremism has been expounded at the highest levels, but turning rhetoric into concrete action has proved to be a challenge. A self-confessed lack of knowledge about how to address violent extremism is prompting innumerable international conferences, and with little impact on how development assistance is being delivered on the ground. Instead, the EU and the international community should focus more on building inclusive and accountable governments and public administration and countering structural factors that drive marginalization. Development aid proposed under the migration fund could be tied to addressing youth unemployment and providing labour intensive infrastructure projects that would link those in the margins to markets and services, as well as taking measures to improve governance, limit corruption and strengthen democratic institutions.