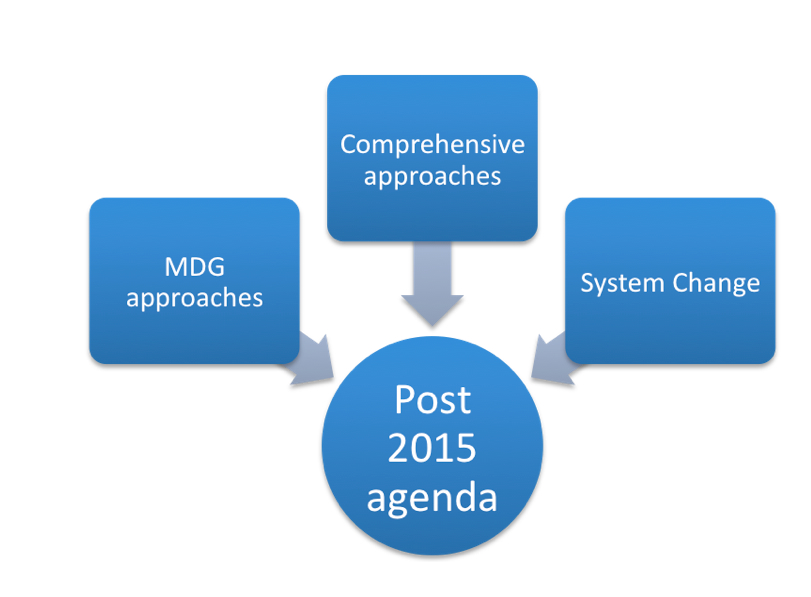

Unravelling the approaches to the post-2015 development agenda

The 2015 deadline for the first global campaign against poverty, the UN Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), is approaching. Global consultations on its successor are underway. Views on the post-2015 development agenda fall roughly into three categories 1: MDG-based approaches, more comprehensive and multidimensional approaches and those that aim at system change.

MDG-based approaches

These approaches prioritize basic needs in global efforts to reduce poverty 2. The rationale behind this is “to encourage sustainable pro-poor development progress and donor support of domestic efforts in this direction.” 3 In the MDG model, these basic needs are clustered into eight goals, subdivided by targets and indicators. The MDGs aim to achieve objective outcomes, which are action-oriented, concise, easy to communicate, and global in nature, while taking into account national realities, differences and priorities. However, the overarching goal of the models within this category may be broader than the original goal of tackling extreme poverty (defined by the World Bank as less than US$1.25 per day), including protecting the environment and peace/security 4. Although many models can be distinguished within this category, they can be roughly divided into ‘conservative’ and ‘extended’ MDG models.

Conservative models

Conservative models focus on poverty reduction and propose either extending the timeline for achieving the MDGs or developing a modified set of broader goals.

These models are usually inspired by donors, multilateral aid and development agencies, and are in line with the 2005 OECD Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness 5. They advocate country ownership, partnership, alignment, harmonization, budget supportand management for development results (MfDR). Conservative approaches fall into three categories:

- Retaining the MDGs with minor revisions (the baseline or ‘roll-over’ proposal) 6. Mark Suzman (Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) and Dr Gaston Gohou (CESS Institute), 7 as well as the MDG Progress Reports on Africa all go in this direction. These proposals do not have widespread support, however

- Retaining the MDG model, adding sustainability considerations for each goal. 9 The “ZEN” framework of the Asian Development Bank emphasizes the challenges of achieving zero extreme poverty (Z), setting country-specific “Epsilon” benchmarks for broader development challenges (E), and promoting environmental sustainability (N) 10

- Modifying the MDGs with greater flexibility at national level (considering the initial conditions of each country and differences in national priorities). 11 The new framework should address the process of how to achieve the outcomes (an ‘outline of means’), rather than focusing only on the results.

Less conservative but remaining within the MDG model are the Millennium Consumption Goals (MCGs). The MCGs are goals for the rich, presented as the opposite side of the coin to the MDGs, which protect the poor. 12 They are conceived as a complementary path to global sustainability as part of broader initiatives on Sustainable Consumption and Production (SCP). Professor Mohan Munasinghe describes the MCGs as a set of benchmarks to be achieved by a combination of voluntary actions by sustainable consumers and producers, supported by enabling government policies. 13

Extended models

Extended MDG models (‘MDG-plus’) entail recalibrating the MDGs to reflect changing economic and geopolitical conditions, increasing inequality, demographic dynamics and challenges. They add new goals based on lessons learnt from the MDGs (see overview below) but follow the same logic as the original MDG model. They are already being implemented in some developing and middle-income countries, like Thailand, where achievement of the MDGs was far more viable. 14

MDG-plus models add new elements to development strategies, especially quality indicators and new issues, like equality, good governance and environment. With such a large number of different issues, however, these models could risk losing one of the MDGs’ strengths: simplicity. The options within this model include:

- Expanding the MDG on environmental sustainability to include issues such as energy and agriculture and the need to mitigate the risk of external shocks caused by climate change and environmental degradation.

- Wider goals differentiated by context, which include cross-cutting issues and a human rights’ focus. 16

- Andy Sumner and Meera Tiwari propose to build on the MDG on global partnership, 17 and to expand MDGs to local ownership with nationally set goals on global poverty issues. 18 Governments would set new national targets and, or pursue both universal and an nationally defined poverty goals. 19

Criticism of the MDGs

The MDGs have received a fair deal of criticism, which contributes to shaping the post-2015 agenda. Here are some of the major points of criticism raised towards the MDGs:

- The MDGs have had distorting effects and negative aspects.

- They represent a reductionist view of development:21 the MDGs were more poverty reduction goals than development goals,22 although reality shows that resource allocation was not necessarily determined by need. They neglect fundamental dimensions of development, like human rights and economic growth.23

- They are based on a limited unifying theory on the structural causes of poverty (weak on social justice: equity, rights, vulnerability and exclusion).24

- They lack theoretical underpinning and consequently focus mostly on concerns raised by aid agencies.25

- They are fragmented in their implementation as well as in their underlying conceptualization of development and means and ends.26

- They offer new instruments for old policies (as opposed to a new development paradigm).27

- They are limited in scope, neglecting certain topics related to material, relational and subjective wellbeing.28

- They lack universality: the MDGs overlook poor and marginalized groups, as well as poverty in middle-income countries.29

- They led to isolated programmes instead of more integrated approaches reflecting the complexity of poverty and of coordinated interventions.

- They have promoted dependency in developing countries.

- They have promoted a top-down approach rather than one based on the participation and inclusion of key actors in design, formulation and implementation.

- They have been misinterpreted and used as a one-size-fits-all framework despite being intended as collective targets (insufficient attention has been paid to specific context at national and local level, although some countries have adapted the targets to their context and priorities).

- Multiple objectives have been defined in different ways, which might lead to overlap and difficulties in assessing overall progress.

- They focus on results and quantity, rather than quality.

- Duty-bearers lack accountability for reaching the goals.

- There is a lack of leadership and ownership.

- There is a lack of political and financial planning for long-term continuation.

- They neglect the role of the private sector.

- They create the illusion that any goal can be met if the right amount of money can be mobilized. 30

More comprehensive approaches

Building on these criticisms and the lessons learnt from implementing the MDGs, a number of proposals move beyond the MDG model and advocate a more comprehensive approach.

The SDG model

Some scholars and practitioners see the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Read our article Lessons learned form MDGs in this dossier) as a form of MDG-plus. Although the SDGs are framed in a structure similar to the MDGs (with complementary targets for each goal), they are more integrated constitute therefore a firstmove towards a more comprehensive approach.

The SDG model originates in a proposal by the governments of Colombia and Guatemala for the Rio+20 process, 31 and is based on Agenda 21 from 1992 (combating poverty especially in developing countries, reinforcing global partnership and protecting the environment). The proposal suggests prioritizing cluster issues to balance socioeconomic growth and the use of the environment, namely: combating poverty, changing consumption patterns, promoting sustainable human settlement development, biodiversity and forests, oceans, water resources, advancing food security and energy (including from renewable sources). 32

The SDG model includes all dimensions of sustainable development (economic, social and environmental) and emphasizes the objectives of sustainable development according to whom? Brundtland report? (poverty eradication, changing unsustainable production and consumption patterns, and protecting and managing the natural resources of the planet). It advocates people-centred goals and universally applicable development at a national level. The principles inspiring this model are those referred to in the Millennium Declaration.

Within the SDG model, the Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES Japan) 33 suggests incorporating the essence of the MDGs (a common set of goals and priorities) into the SDGs with a focus on climate change/energy, water, disaster risk reduction and resilience, sustainable cities, etc. This proposal emphasizes separate national development priorities as well as the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities. 34 Based on different country situations, it prioritizes basic access (for developing countries), strengthening efficiency (for middle-income countries), or lifestyle-changing actions (for developed countries).

Jeffrey Sachs proposes an MDG-style model for the SDGs, which would frame universal goals around the four pillars of sustainable development. 35 His proposal focuses on the triple bottom line approach to human wellbeing: economic development, environmental sustainability and social inclusion. Importantly, these categories depend on good governance at local, national, regional and global levels. 36

Multidimensional models

These models emphasize the interdependence and interconnectedness of elements that are at stake when tackling development (natural resources, health, social protection, food, water management, energy, peace, security, etc), 37 as opposed to the more fragmented and limited approach of the MDGs. 38

Jeff Waage et al. 39 suggest a model based on five guiding principles: holism, equity, sustainability, ownership and global obligation. 40 This model derives from a definition of development as a dynamic process involving sustainable and equitable access to improved wellbeing, expressed in terms of social, environmental and human development. Other approaches focusing on wellbeing apply more comprehensive indicators, 41 taking account of factors like empowerment and options facing the individual. 42

Rights-based models 43 are inspired by the idea of human needs as human rights, 44 and see poverty and social exclusion as a denial of those rights. These models are based on internationally agreed human rights language, principles and standards. They place citizens at the centre and highlight universality and the idea of progressive realization of rights using the maximum resources available. 45 The MDG-human rights nexus concept falls within this category. 46 It sees poverty reduction and human rights are seen as interconnected but distinct endeavours: poverty reduction cannot be resolved entirely through a human rights approach or through empowerment, inclusion or voice. It also entails technical and economic issues, and analytical questions about how to organize economic institutions. 47

In their report “Post-2015 development agenda: goals, targets and indicators”, the Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI) and the Korean Development Institute (KDI) suggest candidate goals to inform the process of selecting successors to the MDGs 48. The CIGI and KDI divide 12 new development goals into three groups focusing on “the essential endowments necessary for individuals to achieve their fuller potential, the arrangements to protect and promote collective human capital and the effective provision of global public goods.”

A global public goods (GPGs) approach addresses issues such as financial stability, the environment, knowledge, peace and security, common goods and resources, which enable human development and economic growth. 49 It sees current problems (poverty, climate change, financial systems, etc) as global challenges caused by unbalances and lifestyles in developed countries, as well as in developing countries, and mainly in the world as a whole. Solving these problems calls for global thinking and collective action. They cannot be adequately addressed by individual countries alone. 50 Pollard and Fischler refer to collective (rather than common) problems. 51

Advocating a GPG approach implies “taking a fresh look at the strategies that countries employ when pursuing their national interests.” 52 While development goals currently focus on national development instruments, 53 the GPG approach could lead towards a model where global development goals are tackled using global development tools.

On this same track, Richard Manning refers to the One World approach, 54 while Andy Sumner proposes the Millennium World. 55 Both address global issues with a focus on climate change, global public goods, goals for climate adaptation, finance, poverty, social insurance, resilience and security. According to Richard Manning, his approach “would encourage policy-makers to give greater weight to tackling systemic global issues (of which absolute poverty would be only one)”. Others than Manning?? would include inequality, the global commons, security, global governance, etc. 56

These comprehensive approaches mark a renewed way of development thinking that was already present during the making of the MDGs but was severely watered down during the final negotiating process, moving beyond the MDG framework and seeking new integrated roads ahead. However, they still work within existing structures, suggesting moderate transformations. The final group of models, which are the most radical, aim at system change.

Models aimed at system change

These models call for a fundamental and transformative change in the prevailing understanding of development, politics, international economics and global governance. They question existing power relations and aim for far-reaching transformations, on the basis of a framework driven by obligations and accountability (rather than a charitable approach), and constructed around the value of global solidarity and a global “new deal”. 57 Following Rolph van der Hoeven: 58 a new global social contract “would guarantee Least Developed Countries (LDCs) concessional resources to achieve inclusion in the world economy and poverty reduction”. This highlights the need for social protection and strengthened global governance to enhance policy coherence for development. 59

Transformative models focus on long-term comprehensive strategies, which require major changes in the current economic, financial, political and consumption systems in developed countries. According to Jan Vandemoortele, the real debate about the MDGs must be about a threefold agenda to reform the global trading system, redress climate change and reduce within-country inequalities. 60

These alternative approaches propose to move from development assistance to a universal global social contract, from growth models that increase inequality and risk to models that decrease inequality, from meeting easy development targets to tackling systemic barriers to progress, and from damage control to investing in resilience. 61 They aim to leave behind traditional donor-recipient frameworks, broadening the scope of actors involved in the process and expanding its geographical scope to a global scenario, moving from economic to sustainable human development, with more participatory and inclusive governance structures. These models are more critical, embracing and politically oriented, and demand structural change to realize this new vision. New ways of thinking must reflect new realities and global concerns like climate change, social justice and inequality should shape the new agenda. Such approaches advocate a set of goals that “contributes to reshaping processes of global governance representing the preferences of humanity”. 62

The recently published European Report on Development 2013 seems to subscribe to the necessity of such transformations, although its core content corresponds more closely to a less radical comprehensive approach. Among its conclusions for a post-2015 agenda, the report emphasizes the vital importance of a transformative agenda, calling for economic and social transformations and for the causes of poverty to be addressed within a new model of development. 63

The many approaches and proposals discussed here are advanced by people in very different situations and with different interests. But they share a stated aim: to advance global development, whether that be by building on existing structures, adding goals and targets for a more comprehensive approach, or aiming to achieve system change. The post-2015 debate will define which model will eventually be chosen after the MDGs expire in two years time. The positioning of the future agenda will show how strongly decision-makers are committed to achieving a just world for all and the extent to which this diversity of approaches has enriched and improved the legacy of the MDGs.

While progress towards achieving the eight MDGs continues with mixed results, the conversation on the post-2015 development agenda is intensifying. The Broker will continue to follow the conversation and the associated events closely (see our article on the post-2015 process here).

Footnotes

- As for the programmatic and technical part of the future framework, these views could be further differentiated with regard to goal-setting, targets, measurability, monitoring and reporting etc.

- The MDGs were built on a set of goals first developed by the rich countries in the OECD strategy “Shaping the 21st Century” (1996). The content was the basis for 2000 document “A better world for all”, whose main features were reflected in the UN Millenium Declaration. See also: Hulme, David: The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs): A Short History of the World’s Biggest Promise.

- Richard Manning (2009) “Using indicators to encourage development. Lessons from the MDGs”. DIIS Report 2009:01.

- The current goals and targets each tackle one of the seven areas addressed by the 2000 Millennium Declaration, namely: development and poverty eradication, peace/security and disarmament, protecting our common environment, human rights/democracy and good governance, protecting the vulnerable, meeting the special needs of Africa and strengthening the UN.

- The evaluation of the Paris Declaration by daRa says that it “remains a consensus model mainly shaped by the main multilateral aid and development agencies” According to Aid Watch.org, despite improvements with regard to international aid, the declaration fails to place human rights and justice at the heart of development or to redress the imbalance of power between donors and recipients. Furthermore, the measurements do not take country context into account.

- Knut-Eric Joslin (2012) “Successors to the MDGs: a summary report” Academics Stand Against Poverty. Reaching the MDGs 2.0. World Vision International (note 27)

- “The Post-2015 Development Agenda: The Case for Retaining the MDGs in their Current Configuration”. Paper prepared for UNECA Regional workshop: Articulating Africa’s position on the post-2015 development agenda. 15–16 November Accra.

- Andy Sumner and Meera Tiwari (2011) “Global poverty reduction to 2015 and beyond”, Journal of Global Policy. The document “100 Voices: Southern perspectives on what should come after the MDGs” also shows little support for this option.

- See “Current outlook on the SDGs: a brief analysis of country positions”. Tokyo Institute of Technology, Institute for Global environmental Strategies (IGES), Titech-IGES Joint Briefing Paper 1, January 2013.

- Asian Development Bank (2013) ‘A ZEN Approach to Post-2015: Adressing the Range of Perspectives Across Asia and the Pacific’, Available here.

- Deepak Nayyar (2012) “The MDGs after 2015: some reflections on the possibilities”. Available here.

- Mohan Munasinghe (2011) “Millennium consumption Goals (MCG): how the rich can make the planet more sustainable”.

- Among the possible targets, Munasinghe includes the following: conservation of scarce resources like energy and water, efficient transport, sustainable dwellings, healthier diets and obesity reduction, healthier lifestyles and greater fitness, progressive taxation and taxes on luxury goods, sustainable livelihoods, reduced workweek and improved working conditions, etc.

- Malcom Langford (2010) “A poverty of rights: six ways to fix the MDGs”. IDS Bulleting Volume 41, Number 1. Among the countries successful in achieving development outcomes is Thailand: it “is on track to meet all of its MDG commitments by or before 2015. As a result, the government has committed itself to an additional set of more-ambitious targets, called MDG+”. Available here.

- Titech-IGES Joint Briefing Paper 1, 2013; Lucy Scott and Andrew Shepherd (2011) “Climate change as part of the post 2015 development agenda” ODI background note, July 2011.

- Janice Giffen and Brian Pratt (2011) “After the MDGs, what then?”. INTRAC policy briefing paper 28.

- Sumner, A and Tiwari, M (2009) “After 2015: what are the ingredients of an MDG-Plus agenda for poverty reduction?”, Journal of International Development, volume 21, pp. 834–843. Available here.

- Andy Sumner and Meera Tiwari (2010) “What has been the impact of the MDGs and what are the options for a post 2015 global framework” IDS working paper 348.

- Andy Sumner’s MDG+ agenda. In “After the MDGs: setting out the options and must haves for a new development framework in 2015” Save the Children, April 2012.

- See Amin’s analysis of the MDGs as “part of a series of discourses that are intended to legitimize the policies and practices implemented by dominant capital and those who support it”. The MDGs: a critique from the South. Samir Amin. Monthly review volume 57, Issue 10 (March 2006). On the negative impact on the ecosystem see: Diana Wall, Rudy Rabbinge “Ecosystems and human well-being: Policy responses” Volume 3 Chapter 19 . Implications for achieving the MDGs, page 578. Andy Sumner and Meera Tiwari “Global Poverty reduction to 2015 and beyond: what has been the impact of the MDGs and what are the options for a post 2015 global framework?”. Fukuda-Parr, S 2013. “MDG strengths as weaknesses”. Great Insights, Volume 2, Issue 3. April 2013.

- Jan Vandermoortele (2012) “After the MDGs: setting out the options and must haves for a new development framework in 2015”, Save the Children.

- David Souter (2013) on the Development-Technology Disconnect. Available here.

- Jan Vandermoortele (2012) “After the MDGs: setting out the options and must haves for a new development framework in 2015”, Save the Children.

- Andy Sumner and Meera Tiwari (2010) “What has been the impact of the MDGs and what are the options for a post 2015 global framework”

- Rolph van der Hoeven (2012) MDGs post 2015: Beacons in turbulent times or false lights?

- Jeff Waage et al. (2010) “The MDGs: a cross-sectoral analysis and principles for goal setting after 2015”. Lancet and LIDC 2010; 376: 991–1023, Page 1008.

- Sakiko Fukuda-Parr (2012) “Should global goal setting continue, and how, in the post 2015 era?”, DESA Working Paper no 17.

- J. Allister McGregor and Andy Sumner (2009) “After 2015: 3D Human wellbeing” IDS in focus policy briefing. Issue 09 After 2015: promoting pro-poor policy after the MDGs.

- According to the Institute of Development Studies, Andy Sumner, 72 or 71?% of the world’s poorest billion people live in middle-income countries (as opposed as two decades ago when 93% lived in low-income countries). See the following articles at The Broker: The new bottom billion: https://www.thebrokeronline.eu/Articles/The-new-bottom-billion/(language)/eng-GB Remaining the MDGs to 2015 and beyond: Time for a new storyline?: https://www.thebrokeronline.eu/Blogs/Goal-Posts-What-next-for-the-MDGs/Reimagining-the-MDGs-to-2015-and-beyond-Time-for-a-new-storyline.

- Michael Clemens and Todd Moss (2005) “What’s wrong with the MDGs?” Center for Global Development CGD Brief. Available here.

- Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores, Republica de Colombia. RIO + 20: Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) A Proposal from the Governments of Colombia and Guatemala. Available here.

- Instead of cluster issues SDGs could be in the shape of a new analytical framework as the nine planetary boundaries proposed by the Stockholm Resilience Center, in Alex Evans and David Steven “Sustainable Development Goals, a useful outcome from Rio+20”. NYU Center on International Cooperation, January 2012.

- The IGES is part of the Independent Research Forum (IRF2015) which provides an independent source of critical thinking, integrated analysis and awareness raising on SDGs and a post-2015 development agenda.

- This approach (including equity) would help to overcome concerns as the ones expressed by India regarding SDGs: “India does not support defining and aiming for quantitative targets or goals towards sustainable development”.

- Jeffrey Sachs (2012) “From MDGs to SDGs”, Lancet 2012: 2206-11, Vol 379.

- Sachs suggests the following SDGs. SDG1: everybody will have Access to safe and sustainable water and sanitation, adequate nutrition, primary health services, and basic infrastructure (electricity, roads and connectivity). SDG2: all nations will adopt economic strategies that increasingly build on sustainable best-practice technologies, appropriate market incentives and individual responsibility (moving towards low-carbon energy systems, sustainable food, urban areas…). SDG3: promote the well-being and capabilities of all their citizens… SDG4: governments at all levels will cooperate to promote sustainable development worldwide. “From MDGs to SDGs” Lancet 2012; 379: 2206-11.

- “Integrated global agreement” referred to by McArthur within the comprehensive type, one of the four perspectives he distinguishes under the typologies of views dominating the Post 2015 debate (conservative, upgrading, geostrategic and comprehensive). However, his distinction refers more to comprehensive in terms of participation than about inclusiveness of issues. In “A guide to the Post-2015 debates”, February 2013.

- The debate remains narrowly focused on economic growth and income poverty. This is perhaps the greatest paradox of our times. Most observers and policy-makers readily agree that poverty must be seen as multi-dimensional, yet its quantification reinforces a one-dimensional – i.e. money-metric – interpretation. See Jan Vandermoortele (2010) “Changing the course of MDGs by changing the discourse”. ARI 132/2010.

- These models pose the problem of a commitment to a set of development goals (as explained by Waage et al 2010) given that the issues which need to be tackled comprehensively make it difficult to reach agreement.

- Waage is director of LIDC and lead author of this study by 19 authors, entitled “The MDGs: a cross-sectoral analysis and principles for goal setting after 2015”.

- See the Broker blog on the Bellagio Initiative as well as the article “Be well…”on well-being: a new development concept.

- Kristy Nowlan et al. (2011) “Reaching the MDGs 2.0: rethinking the politics”. A World vision international policy briefing.

- Save the children (April 2012) ‘After the Millennium Development Goals: Setting out the options and must haves for a new development framework in 2015’, available here.

- Fantu Cheru (2013) “MDGs and Human Rights: daring to breaking out of the liberal box”. Available here.

- For more on the Human Rights approach, see here.

- EA Andersen and MH Jensen (2011) “Getting the MDGs right: Towards the founding of an operational framework for the MDG-human rights Nexus”. Danish Institute for Human Rights, Copenhagen.

- Center for Human Rights and Global Justice, “Human Rights Perspectives on the Millennium Development Goals: Conference Report” (New York: NYU School of Law, 2003).

- Nicole Bates-Eamer, Barry Carin, Min Ha Lee and Wonhyuk Lim,with Mukesh Kapila (2012) ‘Post-2015 DevelopmentAgenda:Goals, Targets and Indicators’, CIGI/KDI Special Report, Available here.

- For an in-depth analysis of GPGs: Malcolm Langford (2009) “Keeping up with the fashion: human rights and global public goods” (PDF). International Journal on Minority and Group Rights, vol. 16, pp. 165–179.

- Giffen and Pratt state that “new paradigms are looking at poverty more broadly, as a feature of developed, middle income and poor countries, and are focusing on thematically based solutions to problems which may be seen as more systemic to all societies rather than just to the poorest countries”. In “After the MDGs- what then?”. INTRAC policy Briefing Paper 28, November 2011.

- Systemic or shared problems (those whose causes and remedies are international) as opposed to common problems (whose causes and remedies are national). CAFOD.

- Inge Kaul (2013) “Global Public Goods, a concept for framing the Post 2015 Agenda?” Discussion Paper 2/2013 GDI/DIE. Page 8. See also: “Collective self-interest” https://www.thebrokeronline.eu/Articles/Special-report-Collective-self-interest.

- Charles Gore (UNCTAD) (2009) ‘Progress under the Brussels Programme of Action’, in: Achieving the MDGs through new development partnerships’, available here.

- Richard Manning (2009) “Using indicators to encourage development. Lessons from the MDGs”. DIIS Report 2009:01.

- Andy Sumner (2010) “Global poverty reduction to 2015 and beyond: What has been the impact of the MDGs and what are the options for a post 2015 global framework”. IDS working paper 348, October 2010.

- Richard Manning (2009) “Using indicators to encourage development. Lessons from the MDGs”. DIIS Report 2009:01, page 66.

- Andy Sumner and Meera Tiwari (2010) “What has been the impact of the MDGs and what are the options for a post 2015 global framework” IDS working paper 348, October 2010.

- The author advocates for the formulation of a set of development goals and targets based on the Millenium Declaration (see note 8). Therefore, his proposal would fall under the first category of MDG-based models, although the idea of a new global social contract as a transformative new framework suggests system change.

- Rolph van der Hoeven and Peter van Bergeijk (2012) ‘Millennium Development Goals in Turbulent Times: Emerging Challenges for Post-2015 MDGs’, available here.

- In “Changing the course of MDGs by changing the discourse” ARI 132/2010.

- For a more elaborated explanation on these essential shifts: “Post 2015: framing a new approach to sustainable development” from The Independent Research Forum (Policy Paper March 2013).

- Brave new World: global development goals after 2015. David Hulme and Rorden Wilkinson. May 2002, The University of Manchester Brooks World Poverty Institute Working Paper 168, Page 15.

- It also emphasizes the need of addressing the instruments and resources to be used in order to meet the goals. It devotes attention to the drivers of development, among them: development finance and a global partnership for collective action to regulate the international financial system and ensure coordination and coherence for development).