Belgian development aid was initially once driven by self-interest. Over the last fifteen years it has made a more resolute effort to genuinely contribute to development.

Belgium began its development aid effort after the Congo declared its independence from the country in 1960. A large portion of this aid went to Belgium’s former colonies of the Congo, Rwanda and Burundi. Many Belgians who had worked in the colonies joined the Dienst voor Ontwikkelingssamenwerking (Development Cooperation Service), which later became the Algemeen Bestuur voor Ontwikkelingssamenwerking (General Board for Development Cooperation, ABOS). As a result, the colonial spirit continued to influence Belgian aid for many years. Rwanda, Burundi and the Congo remain among the poorest countries in the world – ranking 161st, 167th and 168th respectively of the 177 countries on the world human development index. Although there were many factors that contributed to this, it does not reflect very positively on the Belgian aid effort.

Belgian aid was dominated by geopolitical interests for many years. Between 1965 and 1989, enormous amounts of aid were sent to the Congo. During this time the Congo was ruled by the late Mobutu Sese Seko, whose name has become synonymous worldwide with ‘corruption’ and ‘kleptocracy’. Like many other Western countries, Belgium continued to support Mobutu because he played such a strategic role during the Cold War – he was ‘their man’ in Central Africa. In the words of Professor Ruddy Doom of Ghent University, ‘He may have been a bastard, but he was our bastard’. As a result Belgian aid strengthened the position of a leader who would eventually destroy the whole infrastructure of his country and the companies he nationalized. For example, in the early 1980s, the Congo still produced 500,000 tons of copper a year. By the end of the Mobutu era, this had fallen dramatically to a few tens of thousand tons.

But it was not only Belgium that closed its eyes to Mobutu’s corruption. At the end of the 1970s, an International Monetary Fund (IMF) official used the word ‘kleptocracy’ to describe the Congo, and there was little reaction. Willy Kiekens, the long-serving Belgian executive director on the IMF board, calls the ‘politicization’ of IMF support during the Cold War one of the fund’s biggest mistakes.

Economic interests also influenced Belgian aid. In the decades following independence, quite a large number of Belgian companies continued to be active in the Congo. By providing a lot of aid, Belgium could easily defend its own interests. This continued until 1974, when Mobutu started nationalizing the economy.

In more general terms, some Belgian companies saw aid as a way of making large-scale projects easier to sell abroad – a kind of export subsidy. This was also true for aid provided to areas other than the three former colonies. In this way, Belgian aid generated a large number of what are known as ‘white elephants’. The bill for these had to be paid in the 1990s.

The 1990s: A turning point

After the end of the Cold War, Belgian aid to the Congo lost much of its geostrategic importance and Belgium began distancing itself from the Mobutu regime. From then on and until 1999, Belgian aid to the Congo – which was by then embroiled in a civil war – was primarily provided through NGOs. In Belgian political circles, there was growing belief that it would be better to focus development cooperation on countries where Belgium had no colonial past. Nevertheless, Belgium remained highly involved in Rwanda.

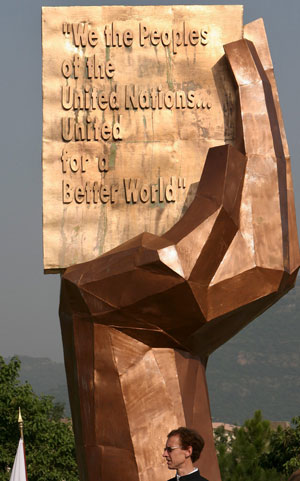

ANP / Olivier Matthys – Jan Vandemoortele, a senior policy advisor at UNICEF, was a founding father of the MDGs. However, he has become critical of how the goals are being interpreted by the donor community.

Since Rwanda’s independence, Belgium had been supporting the majority regime of the Hutus. A special relationship developed between the two countries. When the Tutsis invaded Rwanda in 1990, Belgium adopted a strategy of reconciliation. After the end of the Cold War, the West vigorously propagated democracy and human rights. The UN Arusha plan was intended to bring peace by organizing elections and letting the party of the invading Tutsis, the Front Patriotique Rwandais, participate. The hope was that in doing so the rebels could be integrated in some way into the Rwandan system. The plan went horribly wrong: when the plane carrying the president of Rwanda was shot down in April 1994, genocide followed. After ten Belgian paratroopers had been killed, the Belgian government decided to withdraw all its troops from the UN peace mission. Moreover, at the UN in New York, Belgium also called for the entire mission to be cancelled. This was one of the most dramatic foreign policy decisions ever taken by the Belgian government. Many observers agree that a strong UN mission could have done much to prevent the catastrophe that ensued. After their military victory, the Tutsi rebels took a much more detached attitude toward Belgium, though Rwanda continued to top the list of countries receiving Belgian aid.

In the mid-1990s, the economic aspect of aid became the subject of criticism. The Belgian media devoted considerable attention to a series of projects that had been complete failures. This revealed that Belgian companies repeatedly tailored projects for their own benefit, which was often far removed from the needs of the recipient countries. It also made it clear that ABOS did not function very efficiently and did not do enough to resist commercial pressure. The Ministry of Finance, too, primarily considered the interests of Belgian companies when granting government-to-government loans. The staatssecretaris (junior minister) for development cooperation at the time, Reginald Moreels, took advantage of the negative publicity to subject Belgian aid to a thorough review.

A change of course…

In 1999, the Belgian Development Cooperation Act was approved. For the first time in almost 40 years, priorities for Belgian aid were laid out and its aim defined: ‘to achieve sustainable human development by reducing poverty on the basis of partnerships’. In addition, it specified that Belgian cooperation would be focused on five sectors: basic health care, education, agriculture and food security, basic infrastructure, and conflict prevention and social development. Aid was also to be concentrated more on specific countries.

Although the principle of untied aid was not specified in the act, sectoral specialization made it impossible for companies to continue benefiting from aid. However, successive governments did untie aid, and Belgium came to score well on this point. Government-to-government loans began to be granted based on development relevance rather than corporate greed.

In the late 1990s the administration of Belgian development cooperation was restructured. Belgium followed Germany’s example of separating the Directorate-General for International Cooperation (DGOS), which was responsible for formulating policy and monitoring its implementation, and the Belgian Technical Cooperation (BTC), which took care of the implementation. Also in the granting of government-to-government loans, development relevance has become one of the criteria, whereas before it seldom played any role.

Robrecht Renard of the University of Antwerp claims it was not only the power of the commercial lobby that was limited in the 1990s, but also that of the technical assistants. This group of well-paid specialists had been able to use aid to their advantage for many years. According to Renard, ‘until the end of the 1980s, Belgium still had around 1,000 well-paid official development specialists in the Congo, many of whom had been around in the colonial era. They lost their jobs when we stopped giving official support to Mobutu, so they came and demanded new jobs from the minister for development cooperation, where I was working at the time. Later, they all went to work for BTC, which realized that there was a lot of deadwood among them and quickly set about separating the wheat from the chaff. The BTC could do that much more quickly than DGOS, because of its autonomous status. This was related to the fact that NGO values – like pro-poor, empowerment, participation, grassroots – were infiltrating deeper and deeper into official thinking on aid’.

Dirk Van der Maelen, deputy chairman of the socialist party and then chairman of the parliamentary committee investigating the failures of Belgian aid, praises the reforms. ‘Commercial contamination was a problem in the 1970s and 1980s. Thanks to the measures that were taken, however, there have been no more scandals in recent years. The fact that the themes identified in the 1999 Development Cooperation Act tie in so closely with the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) is the best proof that we were on the right track with the reforms’. The Act did indeed anticipate the MDGs that would be approved at the UN a year later.

Still lagging behind

Belgium was, however, a slow learner in the field of budget support. While other countries had promoted this concept, Belgium for many years stuck steadfastly to the traditional project approach. Until only a few years ago the minister in charge of the budget had to approve every single intervention in the form of budget support.

That fits with the slow process of emancipating development cooperation officials from the ministry of finance and the budget. While in many other countries the development cooperation ministry or department is responsible for policy on the World Bank, sometimes together with the national ministry of finance, this is hardly the case in Belgium. The ‘green’ staatssecretaris (junior minister) for development cooperation, Eddy Boutmans, tried to change that between 1999 and 2002, but met with considerable resistance. In 2001 the ministers of finance and foreign affairs, both liberals, signed a royal decree which explicitly stated that the ministry of finance was solely responsible for Belgium’s policy on the World Bank. The fact that one or two development officials have been posted to the Belgian embassy in Washington since 2002 is a sign that there has been some progress. Their task is to monitor developments at the World Bank and IMF and to contribute the insights and field experience of Belgian development cooperation.

‘One major weakness of Belgian development cooperation’, says Renard, ‘is the lack of a strategic vision supported by all parties, parliament, NGOs and the media. That is much more the case in Great Britain or the Netherlands. Because Belgian governments are usually coalitions of at least four different parties, it is much more difficult to achieve coherence in policy because, for example, the ministers of foreign affairs and development cooperation often do not share the same views on policy’. According to Renard, the fact that Belgium itself is a fragile state with a politicized bureaucracy means that the specialists it sends to aid countries are much more sensitive to the problems of developing countries. ‘Scandinavians and Dutch people are much pushier about telling people in developing countries how to do things and they expect everything to work out right immediately’, Renard says. ‘They often don’t realize how difficult it is to bring about gradual change in a politicized situation’.

Coherence: Words but little action

Coherence is another important theme in today’s development cooperation. Coherence means ensuring, as a donor country, not only that the aid you provide is tailored to the interests of the recipient countries, but also that it does not clash with those of your own policies on trade, security, the environment and so on. Former Minister for Development Cooperation, Armand De Decker, specified coherence as a priority when he took office in 2003, but little was heard of it after that. An official was assigned to write a memorandum on the issue, but nothing ever came of it.

Most Belgian politicians see the development cooperation portfolio as a consolation prize. Marc Verwilghen took office as minister in 2004 after having disappointed in the previous government as minister of justice. In early interviews he denied that he was dissatisfied with his new role. He pledged to make the development cooperation portfolio one that people ‘would fight for in four years’ time’, when the next government would be formed. Less than a year later, he left the job to become minister of economic affairs.

The coherence problem exists partly because, unlike Sweden or the Netherlands, Belgium does not use development cooperation to project the image of a ‘moral superpower’ in the international arena. That seemed to be changing when Guy Verhofstadt, Prime Minister from 1999 to 2007, expressed very distinctive viewpoints on a wide range of international issues such as cancelling debt, opening up markets to developing countries and, last but not least, increasing official development assistance (ODA) in Belgium to 0.7% of the GNP by 2010.

Unfortunately, he failed to live up to these promises. When he left office in 2007 the Belgian ODA stood at 0.43% of GNP. In 2003, Belgian aid did suddenly rise to 0.6% of GNP, as a result of a large-scale, cancellation of the Congo’s debts. That is, however, misleading because the operation did not cost much – the debt was actually as good as worthless – and it did little to improve the Congo’s financial situation, because it had not paid off the debt for several decades anyway. It could, however, be classified as ODA, thereby pushing the aid percentage up considerably.

By 2007 the Belgian ODA had fallen back to 0.43% of GNP (a little over 1.4 billion euros) and is likely to rise slightly to 0.45% in 2008. The goal of 0.7% by 2010, however, seems out of reach. Yet in October of this year, despite the economic crisis, Minister for Development Cooperation Charles Michel proposed a budget that would bring Belgian aid up to 0.6% of GNP by 2009, this time just partly due to a significant cancellation of the Congo’s and Iraq’s debts. It is a question of waiting to see what becomes of this proposal, and whether large-scale debt cancellation will be possible in 2010. Prime Minister Yves Leterme maintains Belgium will reach 0.7% by 2010, even though that would require an extra 900 million euros for DGOS. That is an enormous sum, considering that total ODA in 2008 is only 1.5 billion euros.

This aside, aid spending did rise from 0.38% to 0.43% in 2007, and will probably rise again to 0.45% in 2008. That makes Belgium the sixth largest donor per capita. One thing is certain: the funds allocated to BTC to spend on Belgium’s behalf are set to rise dramatically, both in general and especially in the Congo where the BTC expenditure will rise from 120 million euros from 2002-2006 to 480 million euros from 2007-2012. That is a courageous but risky step in a country with such an unstable and, in some areas, non-existent government. And Belgium is venturing into the lion’s den with a number of interesting programmes that are precisely aimed at improving governance. These programmes ultimately appeal to the political will to tackle problems such as corruption and clientelism. Only time will tell if they will succeed, especially given the often tense relations between Belgium and the Congo. The willingness of the international community, including China, to exert pressure on the Congo will also be a crucial factor.

Development cooperation has continued to have a low ranking in the Belgian political hierarchy. As a result, the ministers and state secretaries are rarely political heavyweights and find it difficult to make their voices heard, despite the need to promote policy coherence. In addition, few members of parliament take real interest in development as a policy issue. But there are exceptions. Minister of Foreign Affairs Karel De Gucht, for example, prevented the Belgian public export insurance company Delcredere from insuring the renovation of a munitions factory in Tanzania because it conflicted with efforts to bring peace to the region. Generally speaking, however, Belgium continues to see development policy too much in terms of pure aid.

Belgian NGOs

Belgium has a wide assortment of development NGOs. They range from large, highly professional organizations to a spectrum of small-scale initiatives. In almost every community in Belgium there are individuals and associations that concern themselves with development issues. There are, for example, 284 local Oxfam shops – 210 in the Dutch-speaking (Flemish) part of the country and 74 in the French (Wallonian) part. Most Flemish NGOs have united under the umbrella organization 11.11.11., which has 341 local committees spread among the 180 municipalities in Flanders. ‘Most of our international colleagues are very jealous of our wide grassroots base’, says Bogdan Vandenberghe, General Secretary of 11.11.11. The Flemish NGO Broederlijk Delen has a very extensive network while, in financial terms, Médicins sans Frontières – which provides mainly emergency medical aid – is the largest, followed by Oxfam-Solidariteit.

Most NGOs run projects in the South. The larger organizations also conduct political campaigns, which have a twofold objective: raising awareness (sometimes combined with influencing policy) and fundraising. The two objectives are not always compatible, but most NGOs acquire more than half of their funding from government in one way or another. There has been much criticism in Flanders – in particular by the think tank De Ekstermolengroep – that NGOs are too fragmented to have much impact. Vandenberghe does not agree, saying, ‘The minister for development cooperation listens to what we have to say about the quantity and quality of ODA. Our political campaigning on the debt burden and the Tobin tax has paid off. And we should be pleased with the progress we have made on mining too, now that Minister Karel de Gucht has made it clear that raw material extraction in developing countries must benefit local populations. That is 100% our line of thinking. Studies show, however, that people still see us as a charity organization, while that is not our main approach. So it’s a mixed picture: we’ve had some successes, but there is still a lot of work to be done’.

In addition to the more or less professionalized sector, there has been increasing attention in recent years for the ‘fourth pillar’ of development cooperation: the fine-mesh network of thousands of private, usually small-scale initiatives for cooperation between North and South. According to Patrick Develtere of Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, who studied the fourth pillar, it weighs in almost as heavily financially as the officially recognized NGOs.

Research: Top of the Great Lakes

After all the turbulence and changes that have characterized the relationship between Belgium and its former colonies, one thing remains certain: Belgium and the Belgians possess a great deal of expertise on Central Africa and the Great Lakes Region. The Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren has an enormous collection of ethnographic, zoological and geological material from the region. It also conducts research in a wide variety of areas, as a result of which departments like geology, anthropology and contemporary history have built up a considerable international reputation. The Institute for Tropical Medicine in Antwerp is a world leader in knowledge of health, healthcare and disease in the Central African region. It is no coincidence that the Belgian Peter Piot, who led the UN AIDS programme for many years, comes from the institute. Thematically healthcare is certainly one of the strongest sectors of Belgian aid.

At international NGOs and the World Bank, too, Belgians are responsible for certain areas of specialization in the Central African region. At both Greenpeace and the World Bank, the leading specialists on the forests of the Congo are from Belgium. Belgium has a number of university centres that focus their research on development and development cooperation, many of which specialize in Central Africa. A ‘PRSP policy support centre’ has been set up at the University of Antwerp. The government has ‘drawing rights’ on the centre’s researchers for a specific number of days, for support in developing policy. According to Renard, ‘That enables us to put our research directly at the government’s disposal. After a positive evaluation, the approach is now being extended to other universities’. Interaction between specialized Belgian academics, NGO workers, journalists and politicians of course deepens the knowledge of Central Africa. That knowledge is internationally recognized and gives Belgium a place among the leading countries when problems in the region are addressed. That is something Belgian diplomats and politicians, since 2000, have considered increasingly important.