The upsurge in violence in Central America’s Northern Triangle is often named in one breath with the drugs market. Although apparently obvious describing an illegal trade that has met with exclusively repressive state responses, assumptions on cause and effect are frequently flawed or blurred. While 2014 may present new opportunities in the growing global debate on alternatives for the failed War on Drugs – for example, Guatemala’s initiative to discuss the outcome of an OAS-led study, which considers a series of options for drug policy reform 1, at a meeting in Guatemala in September 2014, and the ongoing preparations for a Special Session of the UN General Assembly (UNGASS) on drugs in 2016 (insisted upon by several Latin American countries) – a serious policy debate on what role drug policies can play in stemming the violence in Central America is pending. Nowadays, national governments – and the US in particular – and the international community still apply old recipes, in spite of evidence showing that these interventions are predominantly counterproductive and trends suggest that criminal violence will continue to escalate.

The Northern Triangle trilogy

This article is part of a trilogy on the security threats facing the Northern Triangle, that includes Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala. These countries are challenged by the highest levels of youth violence in the world, the highest homicide rates, powerful drug trading groups, weak institutions and political crime. The influx of migrants in the United States reflects the instability in Central-American countries, as people flee to escape violence and poor living conditions. Many national, regional and international strategies have been developed to combat the region’s biggest threats in an integrated way, but often they have been counterproductive.

This trilogy therefore address each of the problems separately – the drug trade, gang wars and corruption – in order to untangle their causal relationship. All three articles present an overview of the security problems and their causes, the different strategies that have been developed to counter the proliferation of drugs, gangs and corruption, and evaluate their success.

This article on the relationship between drugs and violence, by Pien Metaal and Liza ten Velde of the Transnational Institute, untangles the relationship between the drug industry and high homicide rates for more effective violence reducing policies. The article on illicit networks by Ivan Briscoe of the Clingendael Institute sheds light on the intertwined structures of patrimonial relationships and the development of the state after the civil wars in the Northern Triangle, creating a criminal complexion of governments. And the article on anti-gang policies and gang responses by Chris van der Borgh of the University of Utrecht and Wim Savenije of the Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, set out the gang phenomenon and how it’s evolution has been shaped by ineffective policies.

Iron Fist Strategies

In 2012 Guatemalan President Otto Perez Molina called on regional leaders to consider drug market regulation and proposed other alternative drug policies as a way out of the violence crisis. He received the support of a few other Latin-American leaders, which eventually produced an OAS-led analytical report 2, to be used as input for the high level OAS meeting in Guatemala next September. At the UN General Assembly last September Perez Molina explained his motives by saying: “Since the start of my government, we have clearly affirmed that the war on drugs has not yielded the desired results and that we cannot continue doing the same thing and expecting different results”. There are also other signs of changed discourse, of finding ways to apply harm reduction perspectives to the security issue, which have also been seen in recent UN policy documents. 3 This change was long overdue, as widespread Iron Fist strategies (aggressive and repressive state responses, also known as mano dura) have proven quite ineffective and even counterproductive as a policy response to the escalation of local criminal activities. Often directed at those operating on the drugs market and gangs (maras), these strategies have also led to alarming prison overpopulation.

The region – together with the Caribbean – has seen all kinds of clandestine traffic: drugs, people, weapons, animals and many other goods are shipped, driven, flown and even walked in and over the isthmus. Due to its geographical position between South and North America, Central America has a long history of illicit trade. Particularly significant is that the neighbouring regions, the Andean region in the South and Mexico and the US in the North, either produce the bulk of the world’s cocaine, significant amounts of cannabis, and some heroin, or constitute a huge drug consumption market. It should be no surprise that decades of this trade and the unintended consequences of the strategies applied to counter it have contributed to a high concentration of its worse characteristics in Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. These countries, each for specific reasons, are now facing the powerful presence and influence of several high profile drug traffic organizations (DTOs), like Los Zetas and the Sinaloa Cartel, in their territory, which they are simply unable to control.

Balloon effects

The 1990s saw shifts in the routes and strategies used to organize drug traffic to avoid detection and be effective in bridging drugs from South America to the huge North American and European markets. These changed traffic patterns were brought about by reshuffled and renewed groups dedicated to the business, and were in part a response to policies in other regions that had been more or less successful in reducing, dividing or expelling trafficking networks from their territory. These DTOs needed to find less effectively controlled territory and establish new local partnerships, eventually leading them to move into Central America. The Mexican military crackdown on DTOs in 2006, led by its President Felipe Calderón, is a perfect illustration of this ‘balloon effect’, previously experienced by Mexico itself after closing of the Caribbean routes in the early 1990s, and especially with the implementation of Plan Colombia at the end of the that decade.

In Mexico, as in Colombia in the 1980s and early 1990s, the cocaine economy gave a strong impetus to the country’s criminal networks and contributed to a wave of rival violence among criminal organizations aiming to strengthen and consolidate their control of key smuggling routes. Mexico’s criminal trafficking groups, with the possible exception of the Sinaloa cartel, may well be following the Colombian pattern of dispersion and fragmentation. Mexican DTOs – especially Los Zetas and the Sinaloa Federation – have definitely expanded their operational territory into Central America, where they control parts of Honduran and Guatemalan rural and border regions.

Drugs and violence: a causal relationship?

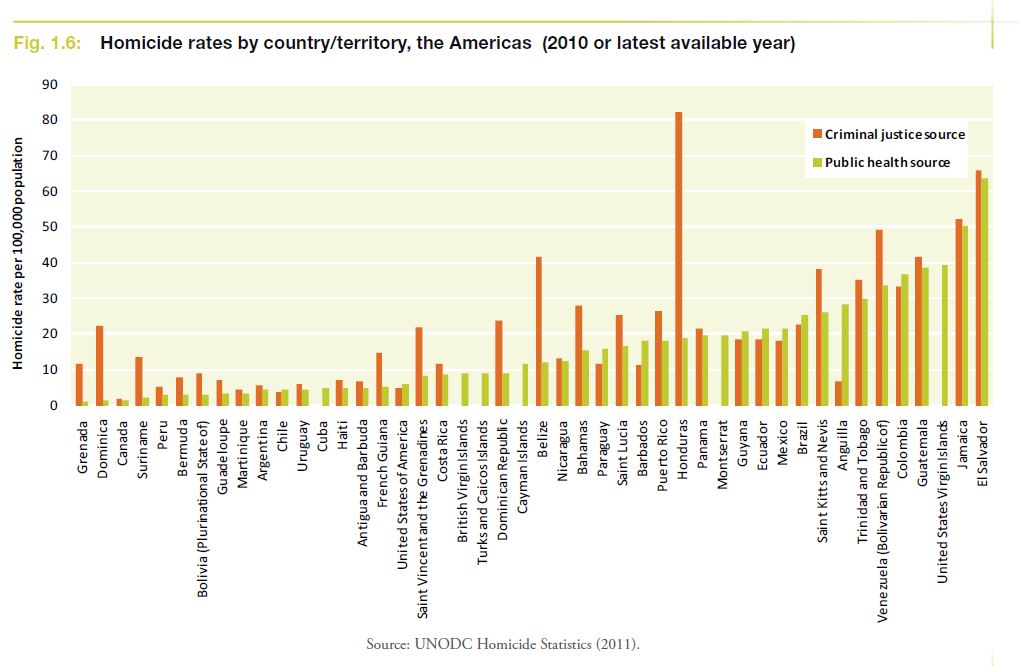

Both El Salvador and Guatemala have been experiencing higher murder rates than those recorded during the civil wars in these countries, which ended in the mid-1990s. It is, however, Honduras – despite having been spared the kind of bloody civil wars experienced by its neighbours – that currently occupies first place on worldwide homicide rate rankings (see the figure below. For these three countries in particular, but also in the rest of the region, the high number of homicides and violent confrontations of the past decade are related to the settling of scores (ajustes de cuentas) and territorial disputes or rivalry between DTOs. But the high homicide rates are also fuelled by police and military interventions that destabilize DTOs and illicit markets, with increased competition and clashes as a result. Exactly to what extent violence in the Northern Triangle is specifically drug-related is thus unfortunately extremely difficult to determine.

It has been argued, for example, that in Honduras the political struggles following the 2009 coup have resulted in links between law enforcement, security forces, politicians and organized criminals to shift to such an extent that distinguishing between drug violence and politically motivated violence has become next to impossible. 4 Furthermore, the quality of homicide typology data – to the extent that they are available at all – is highly variable, making it difficult to determine the share of reported homicides that is related to organized crime or gangs. By extension, with DTOs being a particular type of criminal organization and gangs becoming increasingly involved in the drug trade, it is even more difficult to obtain reliable statistics on the extent to which homicides in the Northern Triangle are related to drug trafficking.

On a related note, the United Nation’s Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and other analyses have argued that drug-related lethal violence is prompted first and foremost by changes in drug markets, rather than by trafficking levels per se, as with the above mentioned ajustes de cuentas. It seems that at least part of the drug-related homicides in Central America can be attributed to such threats to the status quo, either in the form of growing efforts by law enforcement agencies to counter drugs, or changes in the quantity of drugs being trafficked through the region, which causes criminal organizations to vehemently fight for control of territory and markets. 5

These clashes among DTOs, and between DTOs and law enforcement agencies, are thus to a large extent the cause of the region’s high homicide rates, a fact that is all too often overlooked by media outlets eager to portray violent gang members operating under the influence of drugs as the most important ‘sources’ of violence. Although research shows drug consumption patterns are higher amongst people that commit crimes, and drug use rates are also higher within the prison population, it does not support the thesis that drug consumers commit more violent crimes.

A remarkable development of relevance in the debate on the relationship between drugs and violence in the Northern Triangle is the diversification of DTO activities, which has increased notably over the last few years. 6 These organizations have found activities such as extortion, human smuggling and trafficking, kidnapping and weapons smuggling to be very profitable, in some cases causing a partial shift away from drug trafficking. Eliminating the illegal drug trade, by regulating the market, or allowing DTOs to traffic drugs through Central America via ‘a corridor’ to the US, one of the original proposals by Pérez Molina, could definitely contribute, but does not offer the panacea the region is looking for in its attempts to counter its high levels of violence. This diversification of DTO activities is an additional argument that should motivate policy-makers to change the prevalent habit of equating – often without question – drug trafficking to high violence rates, and look at underlying historical and socioeconomic variables instead.

The need for attention to socioeconomic causes of involvement with organized crime is further supported by the fact that the people mainly involved in the illicit drug economy – the human beings behind the homicide figures – are predominantly young and male. Most have a marginal educational background and come from the lowest income groups. They constitute an apparently endless army to be tapped from in this continued cat and mouse game between law enforcement and DTOs. Continued repatriation of gang members from the US to the countries of the Northern Triangle assures that the ranks keep growing.

Assistance and prevailing strategies

Unsurprisingly, the United States plays an important role in the security problems troubling the Northern Triangle, currently expressed in the Central American Regional Security Initiative (CARSI). Originating from the Mérida Initiative – which also included Mexico and the Caribbean – CARSI is designed to build upon existing strategies and programmes, spending US$ 496 million (from 2008 to 2013) on Central America alone. 7 All CA countries have been added to the US administrations’ list of major drug transporters or producers, and narcotics interdiction and law enforcement take the lion’s share of CARSI aid, emphasizing the provision of technical support, equipment and training to local police drug squads and the creation of often military style Special Forces.

Not to be overlooked in this regard is the rather alarming track record of the region’s security and police forces. 8 The involvement of these forces in human rights abuses, corruption and other illegal activities and their cooperation with organized crime is widely documented. Coupled with the largely unsuccessful plans for reform of law enforcement and vetting procedures, we might conclude that the current focus providing support for the military and police is quite risky, if not outright detrimental to the security situation of Central America. And as said above, one of the most important lessons to be drawn from recent experiences in the Americas is that Iron Fist approaches with an emphasis on arrests and drug interdictions often lead to substantial spikes in violence as the drug trade is disrupted, alliances shift and territorial control is disputed. Some initial discussion is emerging on alternative approaches, proposing shifts in focus for law enforcement and drugs markets. 9

All in all, we can thus see a continuation of the Northern Triangle governments’ prevailing mano dura strategies, while these have proved to be remarkably ineffective in stemming the proliferation of violence in the region. Even though Mexico’s militarization of its battle against crime has been widely criticized for its contribution to human rights abuses and violence, it is precisely this strategy which is now being applied and internationally supported in the Northern Triangle. In Guatemala, for example, in spite of calling for alternative approaches in the war on drugs, the president has simultaneously broadened military involvement in anti-crime operations while supporting aggressive approaches to drug trafficking. 10

Redirecting violence reduction strategies

Undoubtedly, the drug market plays a critical role in the criminal violence in the Northern Triangle. But it should be clear that this role is all too often grossly overestimated, supported by stereotypes and superficial assumptions about causal chains. Prevailing drug trafficking control measures often exacerbate violence levels and, though recognized as such, they are still widely applied. An open debate on alternative approaches to drug trafficking and violence needs to continue, considering and discussing harm reduction strategies on law enforcement. Examples to reduce criminal violence can be found in Uruguay, which recently introduced cannabis regulations. In Jamaica, Belize and Puerto Rico cannabis is increasingly being decriminalized. In Nicaragua, the introduction of community policing has reduced violence within communities. And in El Salvador, the government is encouraging negotiations between market actors. It is of the utmost importance that this rhetoric is soon supported by concrete changes in drug policies, legislation and practice, promoted by a shift in the focus of international aid, so as to redirect the Northern Triangle’s violence reduction strategies.

Co-readers

Juan Tokatlian, director of the department of political science and international studies at the Universidad Torcuato Di Tella in Buenos Aires.

And Mabel Gonzalez Bustelo, journalist, researcher and advisor on international security.

Footnotes

- The following proposals from Central America were tabled at a regional summit in April 2012: Firstly, to intensify interdiction efforts while introducing a funding mechanism through which the value of seized drug shipments would be reimbursed by the consuming end destination country. The US, for example, would pay 50% of the US market price for any kilogram of cocaine intercepted in Guatemala, in compensation for the high social costs and law enforcement expenditure of drug control efforts in transit countries. Secondly, the establishment of a Central American Penal Court for drug trafficking offences with regional jurisdiction and its own prison system, to relieve the national criminal justice systems from the high burden of prosecution and incarceration for drug law offences. Thirdly, the ‘depenalization’ of the transit of drugs by the establishment of a corridor through which cocaine could flow unhindered from South to North America without destabilizing the whole region in between. And finally, the creation of a legal regulatory framework covering production, trade and consumption of drugs, without providing further details about how such a regulated market would work or the possibility of varying mechanisms for different drugs. For an overview of current debates in Latin America on alternatives for current policies see http://www.tni.org/article/latin-america-debates-alternatives-current-drug-policy.

- Organization of American States, Report on the Drug Problem in the Americas, and Scenarios for the Drug Problem in the Americas 2013-2025, both May 17, 2013.

- UN Regional Human Development Report 2013-2014: Citizen Security with a Human Face: Proposals for Latin America. In one of its recommendations it refers to “Tackling drug use as a public health problem through prevention, treatment, harm reduction and rehabilitation programmes”. P32 of the executive summery.

- Bull, B. (2011). In the shadows of globalization: drug violence in Mexico and Central America, NOREF. http://www.peacebuilding.no/Regions/Latin-America-and-the-Caribbean/Latin-America-and-global-trends2/Publications/In-the-shadows-of-globalisation-drug-violence-in-Mexico-and-Central-America

- UNODC (2011). Global Study on Homicide: Trends, Contexts, Data, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

- Garzón, J.C., Olinger, M., Rico, D.M. & Santamaría, G. (2013). The Criminal Diaspora: The Spread of Transnational -Organized Crime and How to Contain its Expansion, Wilson Center Latin American Program.

- US Department of State: Central America Regional Security Initiative http://www.state.gov/p/wha/rt/carsi/

- Meyer, P.J. & Ribando Seelke, C. (2012). World Report 2012: Events of 2011, Human Rights Watch.

- Garzon Vergara, J. (2014). Local Markets for Illegal Drugs: Impacts, Trends, and New Approaches, Wilson Center. http://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/local_markets

Siglo21 (2012). Inauguran dos bases militares en Día del Ejército, 30 June 2012. http://www.s21.com.gt/node/246811

Bird, A. (2012). Return of the death squads, Red Pepper, June/July 2012, Issue 184.

Zinecker, H. (2012). Más muertos que en la guerra civil, El enigma de la violencia en Centroamérica.

Costa, G. (2012). Citizen Security in Latin America. Inter-American Dialogue Latin America Working Group, February 2012. - Latin American Newsletters (2012). Pérez Molina shifts gear on drugs. Latin American Security & Strategic Review, June 2012.