For some time now, the call for more flexible approaches to programming in protracted crises has gained support in the community of humanitarian and development professionals. A call that has gained new momentum since the global Covid-19 crisis. Flexible programming allows organisations to remain relevant in fluid environments like humanitarian crises, or while building resilience to shocks and stresses such as drought or local conflict.

The Broker, ZOA and NFP recently concluded a project that created guidance for INGOs and policymakers to take advantage of space for flexible programming that might otherwise be overlooked. Whilst gathering evidence and engaging with policymakers and practitioners on the subject, four common myths and assumptions were discovered that have prevented flexible programming from becoming the standard way of working in fragile contexts, despite the clear benefits for programme outcomes.

Myth 1: Accountability and flexibility are incompatible

Policymakers often assume that by allowing the flexibility to change programme activities and deviate budgets without prior approval, donors cannot track spending, link activities to outcomes, or stay accountable to stakeholder interests. We have learnt that it does not have to be either or, and that certain processes can simultaneously enable flexibility and accountability.

Firstly – justification after the fact – qualitative reporting, and ensuring frequent communication between implementers and donors during the delivery phase can help explain why and what changes were made, as well as how budgets were spent. Secondly, setting boundaries – it can be agreed in advance that changes to the programme remain within a subset of activities, or that budgets can be spent without prior approval up to a predetermined amount. Lastly, planning – building the expectation of change and identifying some alternative activities from the outset can help to guide programmes during emergencies, whilst managing stakeholder expectations.

With these factors considered, donors can stay in the loop and report to stakeholders without inhibiting quick responses by those on the ground who know the situation best.

Myth 2: Flexibility is about acting flexibly in the moment, knowing when, what and how to change

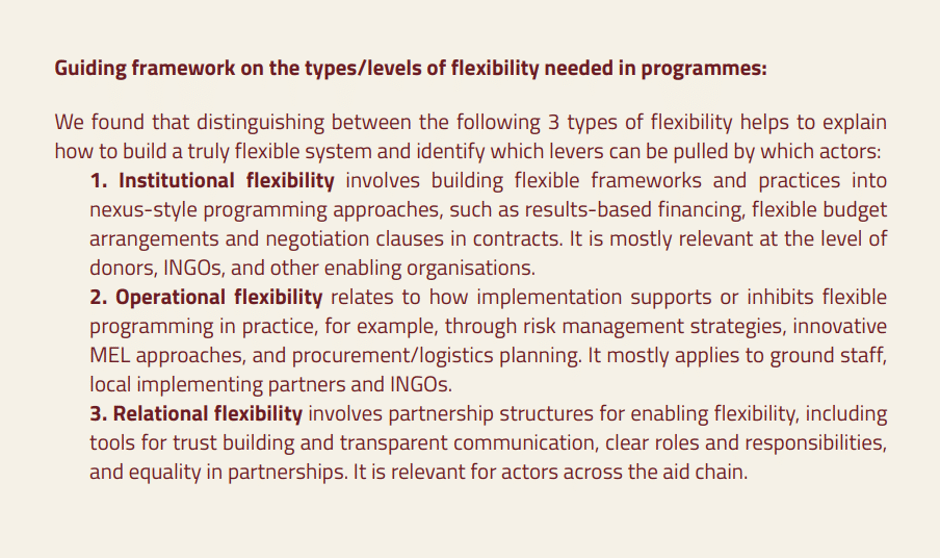

It was established that this ‘operational’ flexibility is only part of the story. Practitioners may have an excellent insight into what is needed, but this also needs to be supported by both institutional and relational flexibility for flexible approaches to be effective.

Those participating in the project found it useful to distinguish between these different types of flexibility, to understand where (and by whom) adjustments are most needed. The guidance that was produced explains how this applies at different stages of the programme cycle (preparation and planning; proposals and contract writing; implementation and monitoring).

Myth 3: Allowing 10-15% wiggle room in budgets is sufficient for acting flexibly during emergencies

Donors have been experimenting during the past five years with new budget arrangements that allow for greater flexibility, including longer-term predictable funds and multi-lateral pooled funds. For programmes that have incorporated flexibility into their budgets, this usually amounts to 10-15% on top of the initial budget for ‘overspend’. However, multi-year flexible funding is often still held at INGO level and does not reach local implementing partners who could otherwise utilise these budgets more effectively, for example, by investing in staff or procuring resources at short-notice. If these types of budget arrangements are not matched with a sufficient amount of discretion at the local level, the potential for development outcomes is in danger of not being fully maximised.

Myth 4: Flexibility is always the best option

It is also important to explore the limitations of flexibility. At the highest end of the spectrum, by having 100% flexibility the whole time, the continuity and integrity of aid can decrease – if you decide to change activities every five minutes, it doesn’t create a good look! We are not advocating for this and also not proposing to deviate too far outside the mandate of the donor, or to suddenly focus on a group of beneficiaries affected by a short-term disaster and leave the original target group of beneficiaries without support.

The key is to remain focused on the overall goals of the programme, and stick with activities that contribute towards those objectives. When changes are impossible, with no entry point or no alternative solution, the best option might be business as usual and trying to keep current activities running to the best of one’s ability.

The lessons learned report and guidelines are available to download here.