Competing customary and legal systems for resource management in the conflicting environment of the Mopti region, Central Mali

The ongoing conflicts in Mali are often taken as one and portrayed in relation to religious extremism, irredentism or plain criminality, overlooking tensions arising from changing socio-political relations at the local level. This is particularly true for the Mopti region, in Central Mali, where customary and state institutions clash in an increasingly fragile context. Failing to grasp the importance of such developments spells trouble for the legitimacy and impact of security and development programmes in this region.

The region of Mopti in Central Mali is populated by three main communities: the Fulani, who are mainly pastoralists, the Dogon, who are mainly farmers, and the Bozo, who are mainly fishermen. Despite their generally peaceful coexistence, there are tensions over resources, particularly in relation to the formal and informal institutions that manage these.

Resource tenure systems in the Mopti region are embedded in societal values, norms and relations and, as such, they reflect power structures. These tenure systems have evolved over time in response to social, cultural, economic and political structures. The customary systems resulting from this process range from resource tenure based on the right of the first occupant to the sophisticated Dina system, which was established in the 19th century by the Fulani chief, Sekou Amadou. More recently, since Mali’s democratic transition in the early 1990s, decentralization reforms have been implemented to address concerns about weak governance, lack of state presence and lack of state legitimacy, as well as resource management issues. As a result, overlapping customary and state systems co-exist.

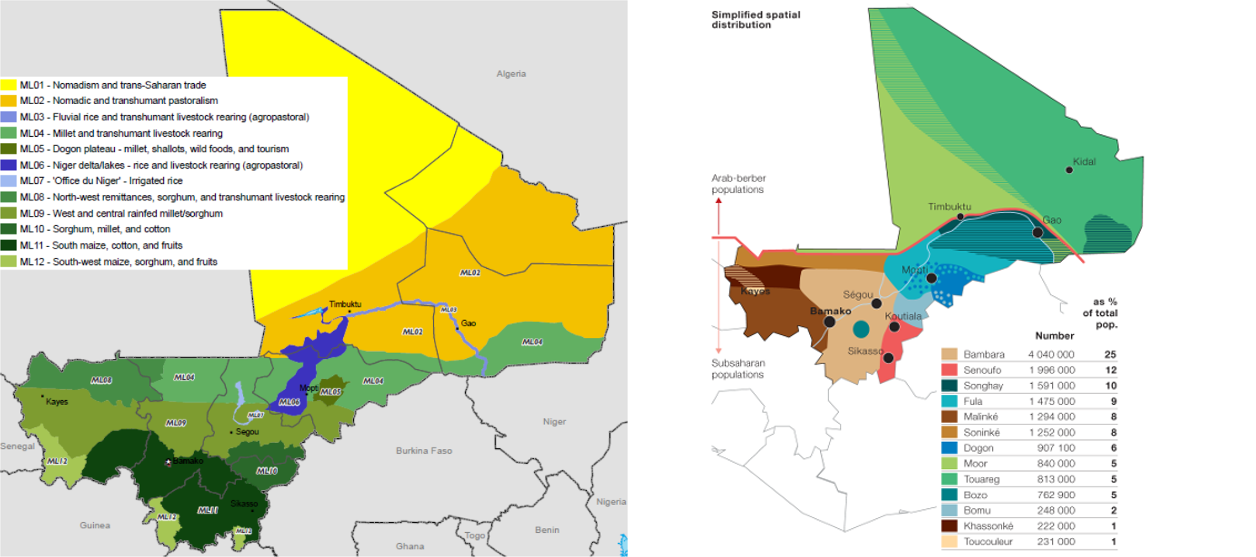

Malian ethnic groups and livelihood zones (sources: left – World Bank (2015) Geography of Poverty in Mali; right – SWAC (2015) The population of northern Mali; click to enlarge)

Livelihood systems in Central Mali

In Central Mali, the most important resources are those coming from agriculture (land), livestock (pasture land) and fishing (rivers, lakes, ponds and channels). The exploitation of these resources is based on the following three production systems, which co-exist and, at times, overlap, depending on the season:

- The pastoralist system (with the breeding of cattle). This production system is associated with a nomadic way of life during the dry season and involves double transhumance: internal transhumance in the Delta (from Diafarabé and Sofara to the pastures of Lake Débo) and a longer transhumance from the Delta to pastures located on land where floods have receded (Seno, Plateau, Gourma).

- The agricultural system (dominated by rice production). This production system is associated with a sedentary mode of living and the cultivation of dry crops such as cereals in dry areas, rice in the flood zone and other crops in the Bandiagara area.

- The fisheries system. This system can be divided into three categories: fishing carried out together with farming; full-time traditional dam fishing; and specialized river fishing. Fishery systems are associated with both nomadic and sedentary ways of life.

Four customary institutions

Stemming from centuries-old tradition, the management of resources in Central Mali is closely linked to traditional power relations between actors, who have historically interacted within four customary institutions that are found in every community.

The first of these institutions is the ‘village’, which is a territorial unit based on the right of first occupancy. At the village level, political power is held by the chief and the religious authority.

The second is ‘lineage’, which is essential in determining who wields political and economic power in the village and who has the right of first occupancy. In Fulani communities, lineage is structured around the suudu baaba (‘father’s house’), which refers to a group of herders with a common ancestor. In Dogon communities in the Bandiagara area, the lineage is also structured around the father’s house (ba-ulum) and family organization is structured around the ginna, an enlarged family group comprising several units with common ancestry.

The third customary institution is the ‘hierarchical structure’, which is based on socio-professional categories and governs relations between social groups. The three main intra-community groups are: (1) nobles: dominant groups made up of nobles exercising key political (chieftaincy), religious (imams, marabouts etc.) and resource management functions (depending on the ethnic group, nobility is dedicated either to land exploitation/farming, as in the Dogon or Bambara communities, or pastoralism, as in the Fulani communities); (2) castes: (blacksmiths, cobblers and bards), which are excluded from politics and agro-pastoral resource management and endowed with important conciliatory and advisory powers; and (3) slave descendants.

Social hierarchy of the Fulani and Dogon

In the Fulani communities, the nobility, or Rimbe, are divided into three social categories: the Weheebe (political elite), Modibaabe (religious leaders), and Seedobe (nomadic herdsmen). The castes, or Waalobe, are ethnic groups whose members generally follow a particular profession. The castes are comprised of the Nyeenyube (lyricists and bards), Wailube (blacksmiths), Gargassabe (cobblers), and Labube (pot and utensil makers). Finally, the slave descendants, or Rimaïbe, have an inferior social position. Historically speaking, land owners were Modibaabe (clergy), whose lands were exploited by the Rimaïbe. In Bandiagara areas, the Dogon social hierarchy is made up of nobles, who are the landowners, and caste people, including cobblers (Djombe) and blacksmiths (Doube).

Fourth is the customary ‘exploitation systems’, which were historically structured around the leydi (a socioecological and territorial unit) in the Niger Delta region and around land units based on the collective property of farms in dry areas. In the Delta, resources used to be managed by the Jowro (‘masters of the land and pastures’, who were Fulani Rimbe nobility); Bessemas (local farming institutions, known as ‘masters of the land’); or members of Bambara and Marka communities, (through their respective heads of lineage, to whom the Jowro had given the responsibility to manage plot cultivation). The power of the Bessemas, which were usually made up of former captives of the Jowro’s from Rimaïbe-populated agricultural hamlets, was quite limited. The Baba Awgal, another local institution, is in charge of water and fisheries. Baba Awgals were managed by the Ji-tu or Ji-tigi (‘masters of the water’), who usually belong to the Bozo or Somono ethnic groups. The Baba Awgals were also under the Jowro’s purview.

In the Bandiagara area, which is dominated by Dogon populations, property was traditionally managed following the family system (the ginna). Each family unit, or manan, managed the production of grains and vegetables like shallots. They were responsible for collective cereal production as well as stock management. Cereal production was designed to feed the whole manan. Meanwhile, virtually all of the vegetable production was intended for commercial sale and managed by individuals or nuclear families. Similarly, in Songhaï communities, each farming unit developed a collective system and each member (cadet, wife and son) managed his or her own farm.

Social tensions stemming from overlapping systems

Such customary institutions are still highly relevant – and legitimate – in Central Mali today. Local communities often find it hard to grasp the role of the government in resource management. Decentralization provided a national framework for resource management in Mali by establishing regions, cercles, and communes as units of local government. Governance units are entitled to manage their own natural resources, while electing assemblies or councils to manage these collectively. This decentralization process, which was accompanied by the adoption of a number of new laws for resource management, has deeply affected agro-pastoral management principles.

This overlap and competition between customary and legal institutions (and laws) for the management of resources often triggers tensions between communities and networks involved in farming, livestock breeding and fisheries, fuelling century-old conflicts between the different communities in the Mopti region. Furthermore, the priority given by most development programmes to agriculture-oriented policies, at the expense of pastoralism, has triggered intra- and inter-communal tension, resulting in the emergence of new power relations within communities involved in resource exploitation. This is especially the case within the Fulani community, where domination between pastoral and farming populations has changed since the colonial period due to the enforced settlement imposed on nomadic populations. These upheavals have upset historical balances.

Changing social relations

- The social position of Seedobe pastoralists (who are Fulani nobility) has been downgraded due to growth-focused government policies that favour sedentary livelihood systems over traditional nomadic pastoralism, which have resulted in a high demand for agricultural land and a reduction in pasture land.

- With the evolution of agriculture, Modibaabe clergy, who used to get their wealth and prestige from the exploitation of their lands by the Rimaïbe, have been forced to reorganize themselves and find alternative livelihood strategies, including by using their thorough knowledge of the Quran or, in some cases, their ‘cherif’ status (directly inherited from the Prophet Muhamet), which enables them to collect money and gifts when they bless fields to guarantee a good harvest and crops.

- The Rimaïbe have enjoyed social and financial advancement, thanks to the new importance given to agriculture. It is not uncommon to find Rimaïbe who have more fields and livestock than the Rimbe pastoralists. In some cases, the latter have become herders for the former.

- Such changes in relationships within castes systems are intrinsically linked to the status of the Jooros (village chiefs), who originate from the Rimbe nobility. Jooros in the Mopti region are losing power and authority, but still enjoy a lot of legitimacy as pastoral leaders.

The current conflicts in Central Mali are mostly related to the technical and operational conditions for resource exploitation, as well as difficulties in defining and delineating agro-pastoral areas – but are also increasingly due to the expansion of the conflict that erupted in Northern Mali in 2012. Fulani pastoralists were the first people to join the jihadist movement MUJAO. As members of MUJAO, they were able to access training and secure weapons with which to fight the Tuaregs from Hairé and Gourma regions, who they accused of stealing their livestock and who used to represent the Mouvement national pour la liberation de l’Azawad in the area in 2012. The relationship between Fulani pastoralists and those Tuareg communities has been tense and conflictual for ages, due to competition over the exploitation of local resources, tenure rights and pastoralist practices.

A need for better grounding of security and development activities

Nomadic herdsmen, whose prestige has declined over recent decades and who rallied around the MUJAO movement, have found their status enhanced. Many young Fulani living in Gourma also joined the MUJAO out of intra-community solidarity between Fulani groups (for instance, the Seedobe and the Toleebe Fulani from Niger). However, the movement was also joined by fundamentalist from Songhaï and Dogon communities from Douentza district. Since 2015, new armed groups have appeared in Mopti region, including jihadist groups (such as Ansar Dine Macina and the Macina Liberation Front), politico-military militia (such as the National Alliance for the Protection of the Fulani Identity and the Restoration of Justice [ANSIPRJ]; the Mouvement pour la Défense de la Patrie du Delta Central, du Hayre et du Seno [MPD]; and the Ganda Izo, the Dewral Pulaaku group), and self-defence groups. These groups are sometimes difficult to distinguish from each other and their followers do not fit neatly into one sociological category.

An interesting example is provided by the Fulani nobles, who are often nostalgic about Sekou Amadou’s Macina theocratic empire, and who accuse current development policies of questioning their ancestral rights. They believe that they have been abandoned (and even persecuted) by the post-colonial Malian state. These nobles are receptive to the Islamist rationale, which they see as an opportunity to restore the rights of nomadic communities.

The complexity of the recurrent and violent crises, as well as the overlapping and competing customary and legal institutions involved in the management of resources, calls for security and development activities to be better grounded on the socio-cultural context in Central Mali. This is vital for security and development programmes to gain legitimacy among local communities – as a pre-condition for them to build sustainable activities and resilience to conflicts.

References

Ba, B. (2010). Pouvoir, ressources et développement dans le Delta Central du Niger, L’Harmattan, p. 47.

Bagayoko, N., Hutchful, E. & Luckham, R. (2016). ‘Hybrid security governance in Africa: rethinking the foundations of security, justice and legitimate public authority’, Conflict, Security & Development, 16: 1, 1–32.

Barriere, O. & Barrière, C. (2002). Un droit à inventer: foncier et environnement dans le delta intérieur du Niger, Paris: IRD, p. 474.

Benjaminsen, Tor A. & Ba, B. (2009). ‘Farmer–herder conflicts, pastoral marginalisation and corruption: a case study from the inland Niger delta of Mali’, The Geographical Journal, Vol. 175 No. 1, March 2009, pp. 71–81.

Cissé, S. (1982). ‘Les Leyde du delta central du Niger: tenure traditionnelle ou exemple d’un aménagement de territoire classique ?’, In Le Roy, É. & Le Bris, É. Enjeux fonciers en Afrique Noire, Paris, Karthala/Orstom: 178–189.

Sangaré, B. (2016). ‘Le centre du Mali: épicentre du djihadisme ?’, Note d’Analyse, Grip, 20 mai 2016, Bruxelles.

Sidibe, S. (2012). Security management in Northern Mali: criminal networks and conflict resolution mechanisms, IDS Research Report 77, p. 25.

Turner, M. (2006). ‘The micropolitics of common property management on the Maasina floodplains of central Mali’, CanadianJournal of African Studies 40 41–75.

Etude Sur Les Bassins De Production Des Speculations Cerealieres De La Region De Mopti http://fsg.afre.msu.edu/promisam_2/reconnaissance_bassin_Mopti.pdf