The Broker recently talked with Laurent Bossard, director of the Sahel and West Africa Club (SWAC) Secretariat. Bossard discussed the complexities of the problems in the Sahel, a region under great pressure, and revealed some positive insights. The red thread running through this talk was that the time to seek regional solutions through increased and deeper regional co-operation is now. Practical and concrete approaches to regional food trade could advance a common political agenda and, thereby, positively impact on the security situation.

This expert opinion is part of our Sahel Watch living analysis

The conflict in Mali has its roots in history, but can also be seen as a product of current economic, ecological, political, security and geopolitical developments in the region.

The Sahara-Sahel region is under a lot of pressure. Mali has been facing a deep socio-political crisis since 2012. Niger, a country grappling with structural food and nutrition insecurity, is caught in tectonic threats, which are sharply increasing along its borders with Libya and Nigeria. Violence in Libya and South Sudan continues. Niger, Chad, Nigeria, Cameroon and the Central African Republic are struggling with Boko Haram. Algeria, Egypt and Tunisia are attempting to keep Libyan violence at bay. Such ongoing instability puts pressure on good neighbourly relations as countries try to prevent conflict from spilling over to their territories. Several stability interventions are now present in the region, with the UN’s MINUSMA mission in Mali mandated to bring stability and peace to the north of Mali and the regional anti-terror operation Barkhane led by the French.

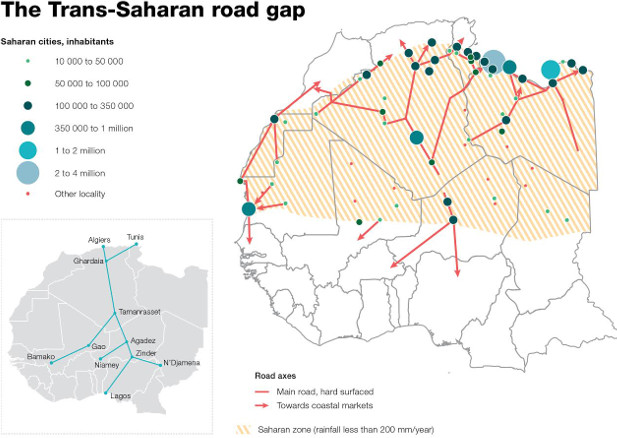

Against this backdrop, Bossard shared the latest insights on the work of SWAC – an international platform for policy dialogue and analysis devoted to regional issues in West Africa. Created in 1976, it is the only international entity entirely dedicated to regional co-operation in Africa, with the mission to enhance the effectiveness of regional action in the 17 countries of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the West African Monetary and Economic Union (UEMOA) and the Permanent Interstate Committee for Drought Control in the Sahel (CILSS). Historically, the work of SWAC included regional integration for agriculture and food security, but now also increasingly covers regional security issues in the Sahel. Bossard said that while most strategies in the Sahara-Sahel focus on short-term impact solutions to address security problems, SWAC also highlights the need to focus on mid- and long-term regional security-development approaches (which are generally unpopular with short-term, results-focused politicians). In the interview, Bossard spoke passionately building a ‘common destiny’, which means creating a common interest to work together on the development of the entire region (see for example figure 1 for the necessity for infrastructure).

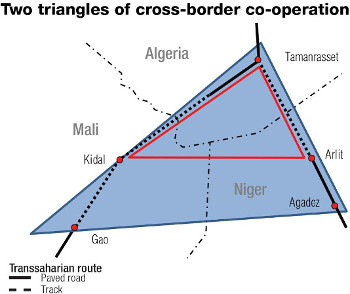

Regional trade, which is already receiving a lot of attention, provides many possibilities to create such a common agenda with shared interests and political will between the Sahara-Sahel countries. Traditionally, Algeria and Morocco have had significant influence over the region, and many of the countries in the region rely on both formal and informal trade exchanges with these two countries. Bossard said that the “two shores of the Sahel” should once again become “the dynamic trading hub between West Africa and the Maghreb”, referring to the clear recommendation in the 2015 Mali report on national and regional perspectives. This report advocates for forward thinking about the potential for economic co-operation and that Mali could renew its centrality within a macro-region from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic, by strengthening cross-border co-operation between the Agadez (Niger)-Gao (Mali)-Tamanrasset (Algeria) triangle (see figure 2). The meat industry, for example, could be a starting point for removing trade barriers between Sahelian and Maghreb countries. Mali is a land of cattle, while Algeria is short on cattle. The problem, according to Bossard, is that trade in cattle is restricted and only processed meat can cross the border to Algeria.

There seems to be momentum for such a ‘macro-region approach’ in Mali since the signing of the peace agreement in Mali in June 2015. The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) recently opened three offices in the northern part of Mali to support the Malian national reconstruction and stabilization efforts. These offices are committed to supporting humanitarian needs and building a resilient society in the region. FAO has signed a Morocco-Mali-FAO tripartite agreement that provides for the training of experts in animal production and activities aimed at expanding access to improved seeds. Through this South-South Co-operation Gateway Morocco will share its agricultural expertize with Mali.

Both macro-region approaches presuppose a long-term and generational project of sustained political, economic and security co-operation, but could also constitute the start of more wide-ranging regional co-operation. Thus, mid-and long-term interventions are a means of achieving security, and while they also advance political solidarity and geopolitical stability, it is also likely to have a positive short-term impact on stability.