Development is mostly about transforming institutions – cultural values, legal frameworks, market mechanisms and political processes. If aid is failing, it is in part because agencies misunderstand institutions and how they change.

When the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, many people in western democracies, including the ‘experts’ of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, assumed that the teetering Soviet Union would quickly transform into an efficient free market economy. Many believed that rapid economic development and greater prosperity would follow.

In reality, other than a tiny minority that profited enormously from dubious processes of privatization, most of the former Soviet bloc was in economic crisis throughout the 1990s. There was a disastrous drop in the standard of living for most of its population. For free marketeers, international financial institutions (IFIs) and development agencies, it was a tough lesson about both the importance of institutions that underpin a market economy and about how much time it takes to develop them. By 2002, the focus of the World Bank’s Development Report was on ‘Building Institutions for Markets’.

Market institutions are not the only challenge. Responding to all the current issues, such as climate change, social injustice or declining resources, requires an unprecedented depth, scale and pace of institutional innovation. Society is struggling to cope with the negative side effects of industrialization and globalization. Humanity’s capacity for rapid technological innovation has far outstripped its capacity for institutional innovation, with potentially catastrophic consequences.

Over the last decade, the concepts of ‘institutions’ and ‘institutional development’ have become heavily embedded in the language of aid. Current development themes, such as markets that work for the poor, good governance and rights-based approaches, demand a strong emphasis on institutions. Yet there is confusion about how to define these concepts and how to translate them into practical methods for analysis. There are also many challenging questions about how institutions evolve and to what extent they can be purposefully designed or changed.Nevertheless, the well-being of people and the environment hinges on finding new ways to transform institutions to cope with the challenges created by technolog-focused development. Interactive forms of society-wide learning need to be evolutionary rather than linear, and must be founded on a solid understanding of the institutional complexity of social systems. These ideas have major implications for the goals, processes and mechanisms of aid.

Which side of the road?

Broadly speaking, institutions can be understood as the ‘rules’ that make ordered society possible, such as language, currency, marriage, property rights, taxation, education and laws. Institutions help individuals know how to behave in a given situation, such as when driving in traffic, bargaining at a market or attending a wedding.

Institutions are critical for establishing trust in society. We put our money in a bank because we trust that all the institutions of the financial system will protect it. We board an airplane because we trust the institutions related to air traffic control and the monitoring of aircraft maintenance to keep us safe.

By definition, institutions are the more stable and permanent aspects of human systems. Some institutions, once developed, lock societies into a particular path of development. For example, the simple convention of which side of the road to drive on is very hard to imagine changing once it has been established.

Many institutions have evolved without much conscious design, and they interrelate with each other in a complex network. The rules of language make it possible for laws to be established, and these laws are then upheld by courts and policing systems. People obey laws because of a whole system of societal beliefs, values and norms. Our lives are embedded in this highly complex web of social institutions, and we take many of them for granted, not questioning their origin or the underlying assumptions and beliefs on which they are based.

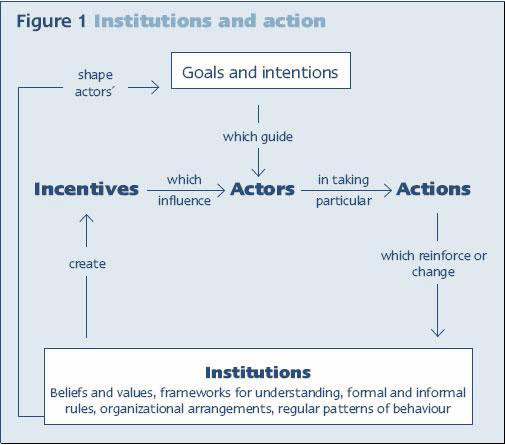

Does bringing about social change require focusing on the individual – following the maxim of ‘think globally, act locally’ – or on social structures? Change is a complex dynamic of social structure and individual action. Institutions essentially create incentives, both positive and negative, for individuals and groups to act in particular ways. People behave either to reinforce or undermine an institution (see figure 1).

Individuals and organizations have their own goals and objectives that are shaped by wider institutional and cultural environments. Deciding to take certain actions at particular times involves many interconnected and sometimes conflicting factors. Choices can counter a dominant institutional influence, whether legal or cultural. Hence, institutions are not a straitjacket for human decision making and action.

A messy web

There is no widely accepted framework for analyzing institutions. The multiple perspectives and lack of practical tools makes it difficult to understand how institutions influence a particular situation, whereas numerous tools exist for stakeholder, problem and power analysis. Yet thinking critically about institutions is key to social change-focused development.

People are rarely concerned with any single institution. Whether our focus is on education, market access, health or the environment, we must consider a messy web of many interacting institutions.

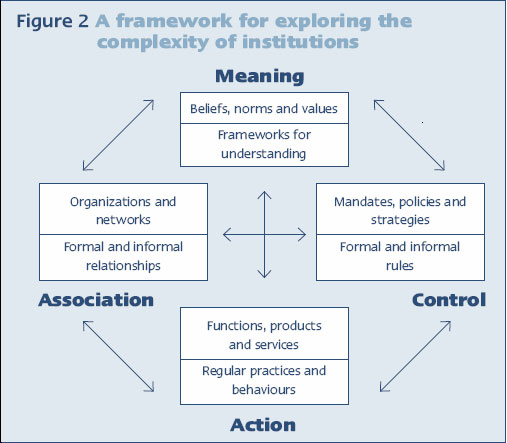

Figure 2 shows a simple framework for asking critical questions about different types of institutions and how they interact. It deliberately takes a very broad perspective, including organizations and regular patterns of behaviour alongside the more narrow view of institutions as merely ‘rules’. The framework is based on four institutional domains – meaning, association, control and action – which connect to structure social interaction. Each of the four domains has two sub-domains. Table 1 describes each of these domains.

Formal and informal institutions are equally important, and often reinforce each other. Figure 2 shows that each domain considers both sides of the coin. Institutional analysis often focuses too much on formal rules, such as policies and laws. This framework shows the importance of asking questions about a wider set of factors that interact to shape the incentives for actors to behave in particular ways.

These four types of institutions link together in a particular logic and hierarchy. Various beliefs and values, along with theories about how the world works, create a drive for purposeful action. To enable cooperation and achieve goals, people create different organizations and relationships. In turn, organizations, whether related to the state, private sector or civil society, have mandates, policies and strategies that guide their actions. Alongside the organizational architecture of society are many different formal and informal rules that structure what organizations and individuals should or should not or may or may not do. This interaction of meaning, association and control results in: a) tasks being carried out and products and services being delivered; and b) consistent practices and behaviours.

Consider the current concern about food quality and safety. Consumer beliefs (‘meaning’) – perhaps about the health risks of genetically modified organisms– and buying behaviour (‘action’) have a significant role in shaping business strategy and government policy making (‘control’). A framework for scientific understanding and research (‘meaning’) underpins food quality and safety regulation and procedures. Organizationally, government agencies are responsible for food safety issues, and many different businesses interact along the value chain (‘association’). Government food safety agencies are mandated to develop policies and establish rules and regulations, while the agrifood industry independently develops its own policies, standards and rules to meet consumer demands and legal requirements (‘control’). These arrangements lead to the institutionalization of supporting actions, such as regular monitoring of imports by a food safety authority, or agribusinesses introducing bar coding and tracing services (‘action’). Some behaviours (‘action’) by different actors, including corruption, may disregard the formal rules and be driven by informal customs and rules (‘control’).

| Type | Description | Examples |

| Meaning | ||

| Beliefs and values | The underlying and often deeply held assumptions on which people base decisions | • Religious beliefs and values• Assumptions about human nature• Beliefs about why some people are poor and others are rich• Beliefs about the extent to which governments should intervene in markets• Values in the management of a business that drive it towards corruption or social responsibility |

| Frameworks for understanding | Language, theories and concepts used to communicate, explain phenomena and guide action | • Language• Economic theory• Principles of law and democratic governance |

| Association | ||

| Organizations and networks | Organizations created by government, business and civil society | • The United Nations• Global corporations• Government agencies• Industry associations• Small businesses• Religious organizations• International NGOs• Producer organizations• Coalitions of national NGOs |

| Relationships and transactions | The ways and means of building and maintaining relationships between individuals and among organizations | • Markets• Global economic forum• Business lunches• Golf games among the ‘old boys network’ |

| Control | ||

| Mandates, policies and strategies | The mandates given or taken by particular groups and organizations, the positions and policies they adopt and the strategies the try to follow | • National constitutions• Articles of association for a business• Global conventions• National poverty-reduction strategies• Corporate strategy for socially responsible entrepreneurship• NGO positions on GMOs• Various forms of government policy (agriculture, health, education) |

| Formal and informal rules | The formal and informal rules that set the constraints for how organizations and individuals can behave in given situations | • Traffic rules and regulations• The way wedding ceremonies are conducted• Laws regarding treatment of employees• Environmental regulations |

| Action | ||

| Functions, products and services | The functions carried out and products and services delivered by government, private and civil society organizations | • Tax collection and administration• Provision of extension, health or education services• Financial services provided by banks• Provision of infrastructure by government• Products produced by industry |

| Regular practices and behaviours | The practices and behaviours that individual repeat in social, economic and political life | • Individual patterns of shopping• Regular behaviours of actors in markets• How people greet each other• How public servants interact with the public |

Complexity and Institutional Change

Intuitively we all know that much of what we deal with in life is ‘complex’. Yet the scientific and engineering mindset of the 20th century has too often led us to try to manage complex situations linearly. And sometimes, linear approaches make a lot of sense. Each time we fly in an airplane we should be thankful that engineers work linearly. However, to protect us from terrorist attack, security systems must function differently. They need to be able to sense the unexpected and to make insightful interpretations from a mass of messy data.

The development sector seems to be embracing the complexity idea (The Broker 9). Understanding institutions is central to grasping the complexity and dynamics of social change. What makes social systems complex is the multitude of interacting institutions, combined, of course, with the often unpredictable nature of human behaviour. Policy makers and practitioners must understand two points. First, no one has consciously designed the institutional frameworks of our societies. They have evolved, over long periods of time, by adapting and responding to all sorts of experiments, new ideas, power plays and external shocks. Second, changing institutional arrangements is no simple task. The results are often unpredictable, with some expected outcomes not occurring and other unplanned changes happening instead.

The Cynefin Framework

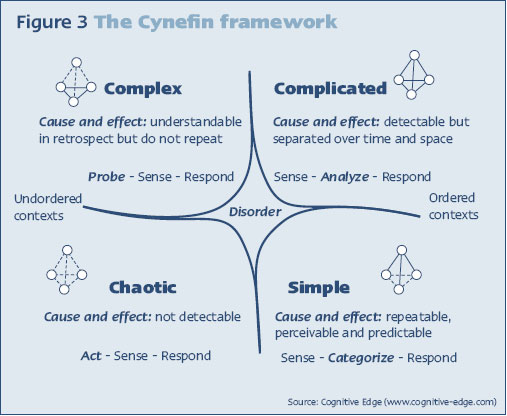

Complexity thinking can help people better understand how to intervene with systems in a structured yet nonlinear way. One emerging practical application is the Cynefin framework. David Snowden, former director of the IBM Institute for Knowledge Management, developed the framework to help managers and leaders better understand the implications of complexity for strategy. The framework can help identify the types of leadership patterns, learning processes and intervention strategies that are appropriate for different levels of complexity.

The Cynefin framework identifies five contexts: simple, complicated, complex, chaotic and disorder (when the context is unclear). This differentiation recognizes that not everything we want to achieve in development is complex. However, it also points out that applying approaches that work for simple and complicated situations to complex and chaotic situations will fail. For example, identifying ‘best’ and ‘good’ practices is fine for simple and complicated situations, but fairly pointless for a more complex problem. Yet, so often this is exactly what development agencies value and demand.

Linear planning, and with it much scientific analysis, is based on establishing clear cause-effect relationships and then using this knowledge to predict the outcome of a design or an intervention. In complex and chaotic contexts, cause-effect relationships either do not exist or cannot be assessed ahead of time. It is necessary to ‘probe’ – to experimentally test out a range of interventions to see which ones work or fail – and then to use this knowledge for scaling up or replicating. This essentially constitutes an evolutionary approach to ‘design’. In chaotic or crisis situations, high turbulence requires acting to restore some degree of order with little time or information for analysis.

Much, but not all, institutional innovation involves engaging with the complex context. And when we talk of failed states we are often in a chaotic context. Yet much development planning and many policy processes focused on institutional transformation operate as if the context is complicated or simple, rather than complex or chaotic.

Institutional Innovation and the Aid Game

Thinking more deeply about institutions and complexity raises major dilemmas for development interventions. On the one hand, tackling poverty, achieving social justice and protecting the environment clearly require institutional transformation. On the other, institutions cannot be effectively changed in a neatly planned, top-down manner, and there is a limited role for outsiders. William Easterly of New York University makes this point in his devastating critique of western aid, The White Man’s Burden. What we have at the moment is an aid system trying to focus increasingly on achieving specific predetermined results. This expectation does not fit the realities of how institutions evolve. Maintaining this approach could lead aid to revert to a focus on easily seen and measured tangibles – infrastructure, health clinics, technology and humanitarian relief. But these interventions alone, though valuable, do not create the conditions for development.

If handled poorly, these dilemmas could severely undermine the western electorate’s support for aid. But sweeping these problems under the carpet is not an option. Consider the potentially devastating impacts of climate change, the fundamental realignments being driven by the emerging economies or the increasingly interdependent nature of the world economy. Avoiding the potentially disastrous consequences of these risks requires an unprecedented level of institutional innovation that is globally coordinated and without the luxury of slow evolution. As Douglass North observed, ‘the interdependent world we are creating requires immense societal change and raises genuine problems about human adaptability’.

An institutional and complexity perspective offers no straightforward solutions, but has several principle-based implications. First, a deeper practical understanding of institutional innovation and the link to complexity is needed by development practitioners and policy makers. The current chasm between theory and practice on this issue must be bridged.

Second, aid must focus not on short-term concrete results but on long term capacities and processes that enable societies to be learning-oriented and highly adaptive. Development trends, such as generic budget support, fail to value the role of civil society as part of the critical conscience that triggers institutional innovation. As Ulrich Beck notes: ‘The themes of the future, which are now on everyone’s lips, have not originated from the foresightedness of the rulers or from the struggle in parliament – and certainly not from the cathedrals of power in business, science and the state. They have been put on the social agenda against the concentrated resistance of this institutionalized ignorance by entangled, moralising groups and splinter groups fighting each other over the proper way, split and plagued by doubts’.

Third, those engaged in development need to distinguish between the simple, complicated, complex and chaotic, and recognize that each requires very different ways of intervening. Dealing with the complex means investing in multiple ‘experiments’ and scaling up what works – an evolutionary design approach to development intervention. By acknowledging that it is often impossible to know ahead of time what will or won’t succeed, we take seriously the need to invest in, accept and learn from so-called ‘failure’.

If investments only focus on sure bets, evolution and transformation is stifled. The big returns on investment may well come from the 20% of successes and the 80% of failures need to be seen as the legitimate cost of experimenting and learning. Most mutations in nature are deleterious, but some mutations lead to highly successful innovations. This is not an anything and everything goes approach. Rather, it involves careful upfront analysis of ‘good bets’, strategic investments in ‘out-of-the box’ thinking and diversified investments in ‘safe-fail’ experimentation. Critically, it requires careful monitoring and learning, not against predetermined indicators, but by drawing on the experiences and observations of those directly involved. The insights and lessons from such learning-oriented monitoring and evaluation are then used to scale up investments in successes and scale down or close off investment in failure.

Clearly we must remain deeply concerned about the results and impacts of development. Yet the evolutionary design principles that make impact possible, while commonsense to field workers, often remain an anathema to the linear logic of policy mechanisms of development planning. Overcoming the current scepticism about aid and development is going to require a much bigger investment in capacities and processes for institutional innovation.

References

Beck, U. (1994) The Reinvention of Politics: Towards a Theory of Reflexive Modernization. Polity Press.

Beck, U., Giddens, A. And Lash, S. (Eds.) (1994) In Reflexive Modernization: Politics, Tradition and Aesthetics in the Modern Social Order. Polity Press.

Beinhocker, E.D. (2007) The Origin of Wealth – Evolution, Complexity, and the Radical Remaking of Economics. Random House Business Books.

Easterly, W. (2007) The White Man’s Burden. Penguin Books.

Hodgson, G.M. (2006) What are institutions? Journal of Economic Issues. XL(1).

North, D.C. (1990) Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

North D.C. (2005) Understanding the process of economic change. Princeton, University Press, Princeton, NJ

Snowden, D.J. (2007) A leader’s framework for decision making. Harvard Business Review. 1 November.

Woodhill, J. (2008) Institutional Change – A Framework for Analysis. Wageningen International Occasional Paper, Wageningen International, Wageningen.

World Bank (2002) World Development Report: Building Institutions for Markets.

Footnotes

- Beinhocker, E.D. (2007) The Origin of Wealth. Random House Business Books.

- Hodgson, G.M. (2006) What are institutions? Journal of Economic Issues. XL(1).

- Easterly, W. (2007) The White Man’s Burden. Penguin Books.

- Beck, U. (Ed) (1994) The Reinvention of Politics. Polity Press.

- Snowden, D.J. (2007) A leader’s framework for decision making. Harvard Business Review. 1 November.