Young people represent more than 60% of Africa’s population, leading to the “demographic dividend” as the new buzzword of the development assistance and business world. Yet how can this booming generation of young Africans be integrated into the labour market and spurr economic growth? Entrepreneurship, if supported through the right policies, can provide an effective solution.

In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, youth employment has been recognized as one of the major challenges of our times. It is also a top policy priority for policymakers in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) who are eager to improve prospects for decent employment among the region’s youth. The factors hampering youth employment in Africa are mostly structural and on the demand side of the labor market. Hence entrepreneurship, including youth entrepreneurship, can contribute to the solution (Page, 2012; Brixiová, Ncube and Bicaba, forthcoming). Some posit that, if equipped with the right skills, mentors, social networks, technology and finance, young entrepreneurs could drive the region’s economic growth and social progress (Roy, 2010).

In the African context, youth typically refers to people of ages 15-35. This definition, adopted by the African Union, focuses on the transition to adulthood, when young people develop critical life-skills through applying their knowledge as well as developing a sense of their own abilities and autonomy. In Africa, young people are striving to achieve economic independence and find their identity in the context of globalization, weakening community structures and an educational system that does not always equip them with skills needed in competitive environments.

Skills and Youth Entrepreneurship

The lack of skills impacts the rate of productive start-ups in the region, including among young people. Recent studies by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) found that while entrepreneurship rates in SSA are high, the majority of entrepreneurs are driven by necessity rather than opportunity. SSA has also higher rates of potential young entrepreneurs than other regions, but a substantial portion (about one third) of them is also driven to entrepreneurship out of necessity. Most new enterprises operate in low value-added sectors such as the retail trade. Further, in contrast to other regions, young entrepreneurs in SSA are less confident than their adult counterparts that they will be creating jobs over the next five years (Kew et al., 2013). 1

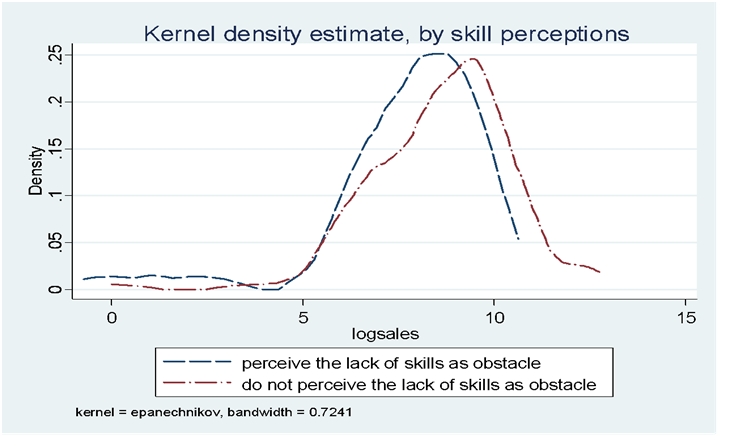

The skill disadvantages of young entrepreneurs relative to their adult counterparts have been well recognized and covered in the literature. Besides lower educational attainments, these include less work experience among young entrepreneurs than adults and fewer links with professional networks. Interestingly though, (potential) young entrepreneurs in Africa sometimes underestimate the lack of business skills as a barrier to entrepreneurship, while – less surprisingly – they recognize access to finance as a key impediment (Herrington and Kelley, 2012). These perceptions vary across countries though – in Swaziland, for example, young entrepreneurs considered skill shortages to be a top barrier to start ups. As Figure 1 shows, young entrepreneurs who viewed the lack of skills as a key obstacle reported good sales performance less often than those who did not perceive skills as an impediment (UN Swaziland, 2013; Brixiová et al., forthcoming).

Figure 1. Kernel density estimate of performance for young entrepreneurs

Source: Estimates based on the UN Survey of Swazi entrepreneurs.

Note: Sales in a typical month. The GEM concept of entrepreneurship, focused on ownership and management as well as the start-up process, was adopted. Training and Entrepreneurial Performance

As the role of self-employment and entrepreneurship in job creation has risen in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, policymakers in Africa and elsewhere have been considering training programmes for entrepreneurs. The focus has typically been on technical, managerial and financial literacy training, with the programmes drawing on evidence that selected skills tend to be correlated with better performance. One of the key challenges in assessing such training programmes has been the lack of evaluation. Utilizing meta-regression analysis of 37 evaluation studies carried out as of March 2012, Cho and Honorati (2013) found that despite mixed results of training programmes, technical and business training worked better than financial training. A mix of skill training and financial support had a greater impact on labor market activity. Positive impacts on both labor market and business outcomes were found to be higher for young people than for adults.

The recent empirical analysis of data from the 2012 UN survey of entrepreneurs in Swaziland found that (sales) performance of firms run by young trained entrepreneurs exceeded that of firms operated by their less trained counterparts (Brixiová et al., forthcoming). Training also had a more positive impact on the performance of young rather than adult entrepreneurs. To be effective, measures should be well targeted and tailored to specific groups. In Swaziland, advanced business training impacted positively on the performance of young entrepreneurs motivated by profits, but not those who entered entrepreneurship mostly for other reasons. Finally, training was found to be less effective in improving the performance of young women than men entrepreneurs.

Policies Supporting Youth Entrepreneurship

Several SSA countries have adopted programmes aimed at stimulating productive youth entrepreneurship. While in principle these programmes are steps in the right direction, to be effective in addressing youth employment challenge, they would often need to be scaled up and linked to better incentives. Most SSA countries are yet to develop comprehensive youth employment strategies and policies that would unlock young people’s employment potential (Brixiová and Kangoye, 2014).

Several international experiences can help in this endeavor:

The OECD (2012) study of high potential young entrepreneurs in Europe underscored the selectivity, where only young people with best projects get support. It argued for intense support per entrepreneur rather than spreading resources widely;

Moreover, and Cho and Honorati (2014) show, packages of measures work better than a single instrument. In fact entrepreneurial training without help with access to credit can just increase the pool of unemployed and potential young entrepreneurs;

Implementing service packages rather than isolated measures was also a lesson from programmes in SSA targeting vulnerable youth. Further, when subsidies are extended, the government should have a clear and credible exit strategy;

Last but not least, training schemes seem to be more effective when administered by the private sector, which is closer to entrepreneurs’ needs.

Still, the government has a role to play in incentivizing the uptake of these schemes. In sum, meeting the employment aspirations of young Africans will require high rates of job creation in employment-intensive sectors, including through entrepreneurship. In turn, productive entrepreneurship requires that the government not only cuts on regulations but also encourages entrepreneurs to develop skills needed in high-productivity and value-adding sectors.

References

Brixiová, Z.; Ncube, M. and Bicaba, Z. (2015), ‘Skills and Youth Entrepreneurship in Africa: Analysis with Evidence from Swaziland’, World Development, forthcoming.

Brixiová, Z. and Kangoye, T. (2014), ‘Youth Employment in Africa: New Evidence and Policies from Swaziland’, in Disadvantaged Workers: Empirical Evidence and Labour Policies, edited by M. A. Malo and D. Sciulli, AIEL Series in Labour Economics, Springer.

Cho, Y., & Honorati, M. (2014), ‘Entrepreneurship Programs in Developing Countries: A Meta Regression Analysis’, Labour Economics, Vol. 28 (June), 110–130.

Herrington, M. & Kelley, D. (2012), GEM 2012 Sub-Saharan Africa Report, GEM and IDRC.

Kew, J., Herrington, M., Litovsky, Y., & Gale, H. (2013), Generation Entrepreneur? State of Global Youth Entrepreneurship, GEM and Youth Business International.

OECD (2012), Policy Brief on Youth Entrepreneurship, OECD: Paris.

Page, J. (2012), ‘Youth, Jobs, and Structural Change’, AfDB Working Paper No. 155.

Roy, R. (2010), ‘Youth Entrepreneurship in Africa: How do We Promote Bottom-up Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies?’, Stanford Social Innovation Review, blog (October).

UN Swaziland (2013), Constraints and Opportunities for Youth Entrepreneurship: Perspectives of Young Entrepreneurs in Swaziland, UN Swaziland: Mbabane.

Footnotes

- The countries were Angola, Botswana, Ethiopia, Ghana, Malawi, Namibia, Nigeria, South Africa, Uganda, Zambia.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the African Development Bank. This note draws mainly on Brixiová, Ncube and Bicaba (forthcoming); Brixiová and Kangoye (2014) and UN Swaziland (2013).