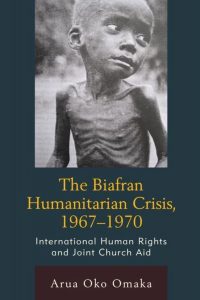

Dr. Arua Oko Omaka, historian at Alex Ekwueme Federal University, holds up an iconic black-and-white picture of a poor and hungry child suffering the consequences of the Biafran war. Omaka is the first keynote speaker for an online dialogue on the decolonization of aid. For him, the picture he is showing his audience clearly symbolises the two sides of humanitarianism: For decades, similar images, of people suffering in the most dire circumstances, have been calling upon our shared sense of humanity, demanding from the privileged to help those who are less fortunate. At the same time however, pictures like this – which continue to drive humanitarianism and are still used to mobilise funding for this cause – also make many, and especially those working in today’s humanitarian and development sectors, uncomfortable. Despite its inherent ‘goodness’ humanitarianism, and the mechanisms that underpin it, are tarnished.

Organised by Kuno, Partos and the International Institute for Social Studies (ISS), the first webinar in a series on ‘The Decolonization of aid’ takes a historical perspective. Hosted by Dorothea Hilhorst, professor of Humanitarian studies at ISS, and Kiza Magendane, writer and knowledge broker at The Broker, this first session is part of the journey towards better understanding of the ongoing debate on the decolonization of the international aid system, exploring the controversies and finding common ground. Taking a historical perspective in this first seminar is vitally important, Thea Hilhorst underlined. “It can help humanitarian and development professionals better understand current beliefs and practices and critically reflect on those aspects that need rethinking.” Bertrand Taithe, professor of cultural history at The University of Manchester, and the second keynote speaker in this session, shared this view. History, Taithe argued, helps us see the inherent complexities and contradictions within the humanitarian project. Not only does it enable us to take a critical look at the past, it also presents us with a mirror. And it is with this idea in mind, that exploring the historical roots of the humanitarian project will help us understand and critically reflect upon today’s humanitarianism, that this first session in the ‘Decolonization of Aid’ series begins.

The article you have before you is a brief reflection of the first online dialogue in the series on ‘The Decolonization of aid’. For the sake of brevity and clarity it is not possible to include the entire wealth of the questions and nuanced reflections that characterised this first session. Rather, the following narrative presents the core message of the presentations by Arua Oko Omaka and Bertrand Taithe as well as the key takeaways of the conversation that followed.

The colonial roots of humanitarianism

When seeking out the beginnings of present-day global humanitarianism, it soon becomes apparent that its roots can be traced back to the colonial project and the abolishment of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. As Oko Omaka explained in his presentation, many Europeans in the 19th century held the belief that they had to ‘liberate’ or ‘save’ the African continent. Its inhabitants were thought ‘savages’ that needed help developing and civilising. And who better to take this lofty mission upon themselves than those who spread the word of God? Thus, in tandem with the conquest of Africa, missionaries and church groups became the first to champion the cause of humanitarian activities, including the provision of Western education, medicine and Christianity.

By referring to Kipling’s famous poem ‘The White man’s burden’, professor Taithe subscribes to Dr. Oko Omaka’s analysis. They both explained that The European colonial project and humanitarian interventions became intertwined at various levels. Humanitarian logic was (mis)used as a ground for the conquest of Africa; the infrastructure used in humanitarian missions were often first established for colonial purposes – as was the case for the humanitarian intervention during Nigeria’s Biafra war; and the colonial rule and an explicitly humanitarian message could, and often did, go hand in hand, resulting in a lasting overlap between the language of colonialism with the language of aid.

Given the complex interlinkages that have begun from the very conception of the two projects, it is a highly challenging undertaking to disentangle the colonial elements from the inherently good facets of humanitarianism – or, in other words, to ‘decolonize aid’. Doing so is a difficult endeavour for all sides, as it confronts us with our painful pasts and, especially, the ways in which we are the products of our histories.

Representing the decolonization of aid

Throughout this series on the decolonization aid, each speaker will be asked to select an image that symbolises the message he or she would like to share with the audience.

For this session Bertrand Taithe chose the symbol of his vaccination passport. Not only does the passport itself have roots in the colonial past, it also represents existing inequalities that can be traced back to these same times. Much work on vaccines and non-Western diseases, such hot-topics in the context of fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, was done during the colonial period. The vaccination passport constitutes both a proof of protection and a ticket to travel to other countries. As such, it is a representation of the unequal distribution of scarce goods – only the privileged have access to this ticket. For Taithe, the vaccination passport is a symbol of our complex history and existing inequalities.

Dutch vaccination passport

Arua Oko Omaka’s image was the iconic black-and-white picture of a starving child that was introduced at the opening of this article. The picture is also a cover of his book on the Biafran humanitarian Crisis. Symbolising the two sides of humanitarianism, it teaches us that good intentions may go hand in hand with complex mechanisms rooted in painful histories – the history of a white saviour and poor, malnourished and dehumanised Africans.

The biafran humanitarian crisis

A more complex network of historical roots

The history of humanitarianism is not only intertwined with that of colonisation, but also with that of decolonization. From the early 20th century onwards, anti-colonial voices became part of the humanitarian cause. This anti-colonialism was about more than formal decolonization – i.e. the liberation from colonial government and the realisation of national sovereignty. It was also about the decolonization as envisioned by radical thinkers like Franz Fanon. True decolonization is achieved through a profound philosophical shift, Taithe explained. And this shift not only pertains to the ‘coloniser’ alone; it also demands the mental decolonization of the formerly colonised and those who are today’s recipients of aid. While formal and institutional decolonization was achieved, for the most part in the middle and late 20th century, this less tangible, social and psychological decolonization is not yet completed. The myth of the ‘white saviour’ and colonial connotations are still present; perpetuated not in the least by the imagery of the poor, starving African that continues to drive the international aid system.

Helpful in achieving this ‘full’ decolonization, Taithe argued, is having a better understanding of the complex origins of humanitarianism – origins that go beyond the European colonial history. Such a nuanced view will enable us to look beyond the false North-South binary that often characterizes our reading of both past and present. While the roots of humanitarianism and colonialism are indeed intertwined, the humanitarian project also has more revolutionary origins, connected to the human rights movement. History provides us with concrete examples that illustrate the diverse and complex sources of humanitarianism. From the Ottoman empire, to India, China and Japan, multiple forms of humanitarian interventions have been developed based on local beliefs and traditions. True decolonization then, also means that we should not take ‘the West’ as epicentre of humanitarianism. Rather, Western development aid should be understood as one component of a much broader and global collection of efforts, movements and international relations. Historical as well as contemporary examples enable us to gradually form a more complex and nuanced conception of humanitarianism – a conception that can be truly decolonized.

Questions for the future

The rethinking of and reflection on current humanitarianism is widespread and in full swing across the globe. For Partos, KUNO and ISS, this first session in ‘The Decolonization of aid’ series, was only the beginning. “Six more will follow,” Thea Hilhorst noted, “which means that it is very legitimate to end this seminar with a lot of questions.” And indeed we did. Taking a step back to look at the complexities of history provided participants with the humbling insight that we are on a complex and challenging journey and many questions remain, as yet, unanswered. Some questions that were raised include:

- How can humanitarianism decolonize completely and entirely when there is still such an unequal distribution of power and resources between North and the South?

- How can we say, with confidence and conviction, that humanitarianism is fully decolonized if the language used still overlaps with that of colonial times?

- Given the long-standing power differences and large inequalities in the world, is it possible at all to achieve a state of true psychological decolonization and equality?

- Humanitarianism historically enabled (African) states not to invest in their own development – including the state’s economy, health care, education, infrastructure. Must true decolonization imply a full withdrawal of humanitarian aid?

- How is the decolonization of aid related to other grand issues of our times, including climate change, increasingly restricted space for civil society, and increasing inequalities within countries?

Despite these difficult questions and ongoing complex interlinkages between colonialism and humanitarianism, our conclusion should by no means be the abolishment of humanitarian and development aid. Thea Hilhorst and Dr. Omaka reminded participants that humanitarianism is, first and foremost, rooted in the conviction that human dignity should not be limited to a particular region. “The aim of saving one life, anywhere, is worth fighting for,” Bertrand Taithe further added. “The conversation we are having should not slide into a discourse of denouncing or vilifying humanitarianism.” If we do so, we run the risk of “throwing out the proverbial baby with the bathwater.” In other words, while the current international aid system does have a colonial stain, it is possible to ‘save the baby’: We can decolonize the international aid system without losing or questioning the fundamental principles of humanitarianism and international solidarity.