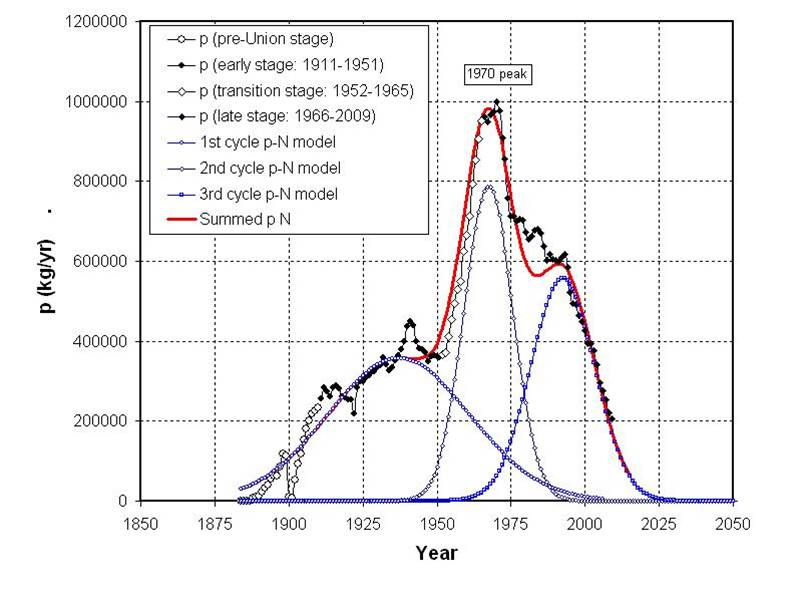

The South African economy has been built on mining. Of all the gold ever mined by humans on planet Earth in all of recorded history, 40% has come from the Witwatersrand Goldfields. These have now reached the end of their productive life (see figure 1) and the industry is shedding jobs in the tens of thousands as investors move to more lucrative destinations. This has caused severe turmoil in the mining industry, coming to an ugly head in 2012 when police used lethal force against striking miners in what has been dubbed the Marikana Massacre.

This has also set the political scene into which an environmental issue has being playing itself out – acid mine drainage (AMD). AMD is the result of oxidization of iron pyrite (fool’s gold), closely associated with the ore bodies that host gold, uranium and coal in South Africa. Stated simplistically, the pyrite is highly reactive to oxygen, which causes the generation of acid, often assisted by the presence of a bacterium called Thiobacillus feroxidans. This is not usually a problem when active mining occurs, but as soon as mining ceases, the voids flood and when the level reaches the lowest shaft opening to surface, a process known as decant occurs. The Witwatersrand Goldfields consist of four discrete mining basins, each hydraulically disconnected from the rest by means of geological structures such as dykes or faults. All mining companies within each basin have interconnected their underground workings in order to share the cost of dewatering as well as to provide for alternative escape routes in the event of underground disasters where rapid evacuation of a large work force might be needed. This means that as each company becomes marginal and ceases to operate, the burden of pumping is redistributed over a decreasing number of operating entities. This accelerates the rate of demise for the remaining companies still operating and is known as the ‘last man standing’ principle.

The first decant to surface occurred in 2002 in the Western Basin outside Krugersdorp, when AMD at a pH of 3 started to flow into a small stream that had not been flowing in living memory. The volumes were significant, peaking at around 50 million litres per day (Ml/d), but flowing at steady state at an average of 27 Ml/d since then. This triggered an environmental NGO to go on the offensive by accusing mining companies of negligence and government of incompetence.

This specific NGO1 has increasingly occupied a high media profile, taking this story to a global audience. The message conveyed by this NGO is based on a seductive narrative that suggests, when distilled out into key components, the following:

- The mining industry has been greedy by maximizing profits through the externalization of liabilities, so it must now be held legally accountable for the clean-up.

- The state has been both incompetent and uncaring, so it has merely fudged the issue for more than a decade.

- AMD is radioactive, because of the presence of high levels of uranium.

- AMD is created in the mining void and will thus be a perpetual problem.

- The government will have to intervene, which means that the taxpaying public will be forced to pick up the cost in perpetuity.

In reality however, none of this is actually true. The mining industry has only done what it has been allowed to do by the regulatory authority. In essence, the gold mining industry sustained the Apartheid regime during the era of comprehensive economic sanctions against South Africa, so it was encouraged to maximize profits in order to maximize revenues to the state.2 This it did by externalizing all environmental liabilities, effectively taking them off the balance-sheet and out of the regulatory domain. If anything is to blame then, it has to be a failure of the regulatory regime from 1961 to 1994 when mining was at its peak (see figure 1). To blame the last few companies still left is disingenuous and will merely hasten the demise of a deeply embattled industry, with major social consequences in the form of job losses. The government is not uncaring, merely overwhelmed by the sheer complexity of the issue, a factor exacerbated by aggressive NGO behaviour that is now starting to represent vigilantism as they take the law into their own hands in the perceived wake of a failure by the state to do what they believe should be done. AMD is also not radioactive, because the presence of uranium is highly dependent on the prevailing pH and redox conditions. More importantly, AMD is not created in the mine void, which is merely a conduit for water flowing from the many surface tailings dams, wetlands and rivers. The current focus on corrective measures, driven by this aggressive NGO, is on treating the water as it decants, which ignores the overall complexity of the problem.

Figure 1. Gold production in South Africa shows three discrete sub-cycles. The first peak in 1930 was shallow mining, the second peak in 1970 was deep level mining and the third peak in 1995 was recycling from gold tailings dumps. Source Hartnady (2009).3

AMD and social conflict

AMD in and of itself has spawned a significant amount of conflict between the mining industry, the state and large portions of an increasingly angry public. However, this is an oversimplification of the problem, because in essence the AMD issue is actually about transitioning from an extractive economy to a future as yet ill-defined beneficiation4 economy in which the environmental externalities of past government policies of state survival increasingly manifest as constraints to future development.

South Africa has not fared well in the wake of the global economic crisis, with officially reported unemployment levels being in the order of 25%, but unofficial figures are likely to be closer to 40%. This has triggered massive social unrest in its own right. Added to this has been the failure of the state to deliver services. This has triggered what is now known as ‘service delivery protests’, which are in actual fact riots of an increasingly violent nature, resembling the situation in the 1980s and 1990s where government lost effective control as security forces were stretched to breaking point.

The AMD issue needs to be understood therefore as a nested environmental scarcity problem that is magnified by the other dynamics in which it is embedded. Arguably the best example is the Western Basin, centred on the Wonderfontein Spruit, which is a highly impacted wetland system that drains one of the most uranium contaminated landscapes in the southern hemisphere. Major rioting has occurred in areas of Bekkersdal with the police being stretched to their very limits in the post-Marikana context. In the recent month alone, two major riots have occurred in Krugersdorp, both of which have spilled over onto mining property where machinery was destroyed and operators escaped with their lives. In both of these recent cases, the police were absent, suggesting that the state is losing its capacity to control social unrest on such a broad front, much like the situation in the 1980s when South Africa slowly imploded into a situation of increasing ungovernability, stopped only when a new constitution was negotiated and political prisoners like Nelson Mandela were released to normalize the country.

This poses the question about the desirability of a highly aggressive NGO, claiming to seek nothing more than the enactment of the national constitution that gives all a right to an environment that is safe, but in effect has become a vigilante taking the law into their own hands. A recent thesis5 by an advocate has shown that the use of legal instruments in the fight against AMD is driving conflict rather than mitigating it.

Some future scenarios

The AMD issue in South Africa is highly complex and is an excellent ‘experimental’ site for those interested in environmental conflict resolution. The outcome at this point of time is unclear, with two possible future scenarios. The optimistic scenario is based on the remaining mining companies redefining themselves as rehabilitation companies instead. This will extend the life of marginal mines by a decade or two, buying time to develop more sophisticated solutions in the form of ‘closure mining’ or ‘rehabilitation mining’. The revenues from gold extraction can pay for the removal of the hazardous tailings dams, for possible placement back into the void, thereby closing it out forever. This will need consensus to be built around the concept of closure mining6, with new partnerships between the mining companies and the state. The pessimistic scenario will see South Africa slowly implode as the massive job losses from the mining industry are not replaced by viable livelihoods elsewhere and foreign capital increasingly takes flight. In this scenario well-meaning environmental NGOs can create expectations that fuel this propensity for violence, eroding the sovereign authority of the state by becoming a vigilante-styled uber regulator, stepping into the perceived breech arising from a failure by the state to project its authority. In this scenario the gradual erosion of state sovereignty by NGOs could see state failure starting to occur as an unintended but serious consequence.

Footnotes

- This NGO is not being named for two reasons. Firstly, it is extremely aggressive in issuing threats of litigation to any entity saying anything about it, claiming libel. Secondly, the name is irrelevant in the context of this report, which is more about strategic-level processes than details of individual organizations.

- Turton, A.R. 2009. South African Water and Mining Policy: A Study of Strategies for Transition Management. In Huitema, D. & Meijerink, S. (Eds.) Water Policy Entrepreneurs: A Research Companion to Water Transitions around the Globe. Netherlands: Edgar Elgar. Pp 195 – 214. Turton, A.R. 2010. The Politics of Water and Mining in South Africa. In Wegerich, K. & Warner, J. (Eds.) The Politics of Water: A Survey. London: Routledge. Pp 142 – 160.

- Hartnady, C.J.H. 2009. South Africa’s Gold Production and Reserves. In South African Journal of Science, No. 105. September/October 2009. Pp 328-329.

- The concept of beneficiation is entering mainstream political discourse, most notably after the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA) recently announced its intention of withholding support from the ruling ANC in favour of the creation of a new political party that favours nationalization of land and minerals, with the beneficiation of those minerals as a key element. This remains an ill-defined policy, so the reader can assume beneficiation to mean adding value to resources, as opposed to merely exporting those resources in raw form to later reimport manufactured goods.

- Botha, E. 2013. Management of Conflict in the West Rand Goldfields due to the Acid Mine Drainage, unpublished thesis submitted to the Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences Centre for Environmental Management, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein.

- Stated simply, closure mining intends to align the final outcome of the mining process with the broader interests of society in a post-mining future economy. The objective is thus to scavenge whatever remains while simultaneously rehabilitating the landscape to a point where it can be returned to productive use albeit in a highly modified format.