The concept of social entrepreneurship has been caught up in its own popularity and a variety of definitions have emerged. Amid the general confusion, four schools of thoughts can be distinguished, each of which emphasizes a different outcome (income generation, social impact, job creation, and broader social change) and attaches different degrees of importance to the economic, social and governance values of social entrepreneurship.

Social entrepreneurship is increasingly popular as a way of doing business while achieving a social and economic impact. However, this rapid rise in popularity (see box ‘The rise in popularity of social entrepreneurship’) brings with it the danger that social entrepreneurship will be misunderstood or even abused. Businesses that look beyond corporate social responsibility (CSR) and NGOs that are introducing entrepreneurial values into their organizations are experimenting with the concept of social entrepreneurship and moving towards each other.

At the same time, all around the world small social enterprises are being set up by individuals who believe in the potential of ‘doing good’ in an entrepreneurial way. Their main challenge is finding a balance between making a social impact and surviving financially – or even growing – in an environment of hard competition. The result is a blurred landscape in which it is difficult to define exactly what social entrepreneurship is.

To what extent, for example, can an entrepreneur who sells a product or service that helps the poor and uses the profits to buy a luxury car be called a social entrepreneur? Or an NGO under pressure to be more self-reliant to finance its social mission that starts a shop or restaurant to diversify its income?

The rise in popularity of social entrepreneurship

More people than ever before are setting up social enterprises. However, for most countries, data on the number of social enterprises is not available, as no separate research has been done. With no officially recognized legal form, social enterprises are untraceable. Data to underpin this trend therefore comes mainly from the United Kingdom, where social enterprises are classified under the legal form ‘community interest company (CIC). In a national survey conducted in the UK in 2011, 14% of social enterprises indicated they were two years old or younger. This is more than three times the percentage of traditional small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs), only 4% of which were two years old or younger. An estimated 68,000 social enterprises in the United Kingdom contribute £24 billion to the economy, according to Social Enterprise UK.

Overall, the debate on social entrepreneurship has expanded in various types of institutions. Educational institutes like Harvard University (US), INSEAD (France), Stanford University (US), Roskilde University (Denmark), Utrecht University (Netherlands) and the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (India), have developed research and training programmes. International research networks have also been set up. Examples are the EMES European Research Network, which has been working on social entrepreneurship with research centres from most EU member states since 1996, and the Social Enterprise Knowledge Network (SEKN), formed by leading Latin-American business schools and the Harvard Business School in 2001.

Several foundations, including Ashoka and the Schwab and Skoll Foundations, have established training and support programmes for social enterprises and social entrepreneurs. The European Commission launched its Social Business Initiative with a top-level conference in 2011. The initiative aims to create a favourable climate for social enterprises, as key stakeholders in the social economy and innovation.

The growth of social entrepreneurship, particularly in emerging countries, is pointed out in a recent report by Social Enterprise UK. The network receives a constant stream of delegations from countries like South Korea, Brazil and India. These countries are going straight for social enterprise, in the same way that countries without infrastructure for landline telephones jump straight to mobile technology. 1 So far, however, South Korea is the only country in East Asia which has passed a law defining and promoting social enterprise. 2

Definitions of social entrepreneurship

The academic and business communities have devised several approaches to social entrepreneurship, mostly originating from Europe and United States, which have shaped the debate on what social entrepreneurship is. In the US the focus lies on individual entrepreneurs and their leadership skills, while in Europe social entrepreneurship is more related to the organization and the broader network in which it operates. However, on both sides of the Atlantic, four schools of thoughts can be distinguished, each focusing on different aspects of social entrepreneurship: income generation, social impact, job creation and change agents. Each weighs the economic, social and governance dimensions of social entrepreneurship differently.

The first school of thought reflects a more commercial vision, equating social entrepreneurship primarily with earned income. 3 Proponents of this school consider financial self-sustainability as important as a social mission. 4 Social enterprises seek to make a profit, or at least not to make a loss. They are non-dividend companies designed to address a social objective. 5 In this way they can compete with commercial businesses in the market and increase their effectiveness.

By contrast, the second school of thought emphasizes social value rather than income generation. Whether an organization actually engages in commerce is beside the point; the key is to create solutions to social problems that go beyond traditional philanthropy. 6Ashoka, the largest network of social entrepreneurs worldwide, defines social enterprise as disruptive innovation in resolving social problems in an entrepreneurial way. 7 It is the impact on local communities that matter. The initial idea of using social innovation to solve everyday problems with new services and products can be placed in this school. However, social innovation has changed as a concept over the years and now includes a focus on the process of innovation with new forms of cooperation to find sustainable solutions to problems in society. Such an approach fits more in the school of thought that we categorize as change agents. 8

The main objective of the third school is to create employment for people like the low-qualified unemployed or the disabled, who are normally excluded from the labour market. The mission of ‘work integration social enterprises’ (WISEs) is to integrate excluded members into work and society through a productive activity. 9 A recent successful example is The Specialists, 10 a for-profit consultancy firm from Denmark that almost exclusively hires autistic people. Their core motivation is ensuring that more people with autism will have employment and good working conditions. 11

The last school of thought defines social entrepreneurs as change agents. 12 The objective is not just to solve a single social problem, but to find sustainable solutions to the causes of problems within a broader context and embedded in a process of continued learning and community participation. Social entrepreneurship in this sense means creating viable socioeconomic structures and relations that yield and sustain social benefits. 13

A blurred landscape

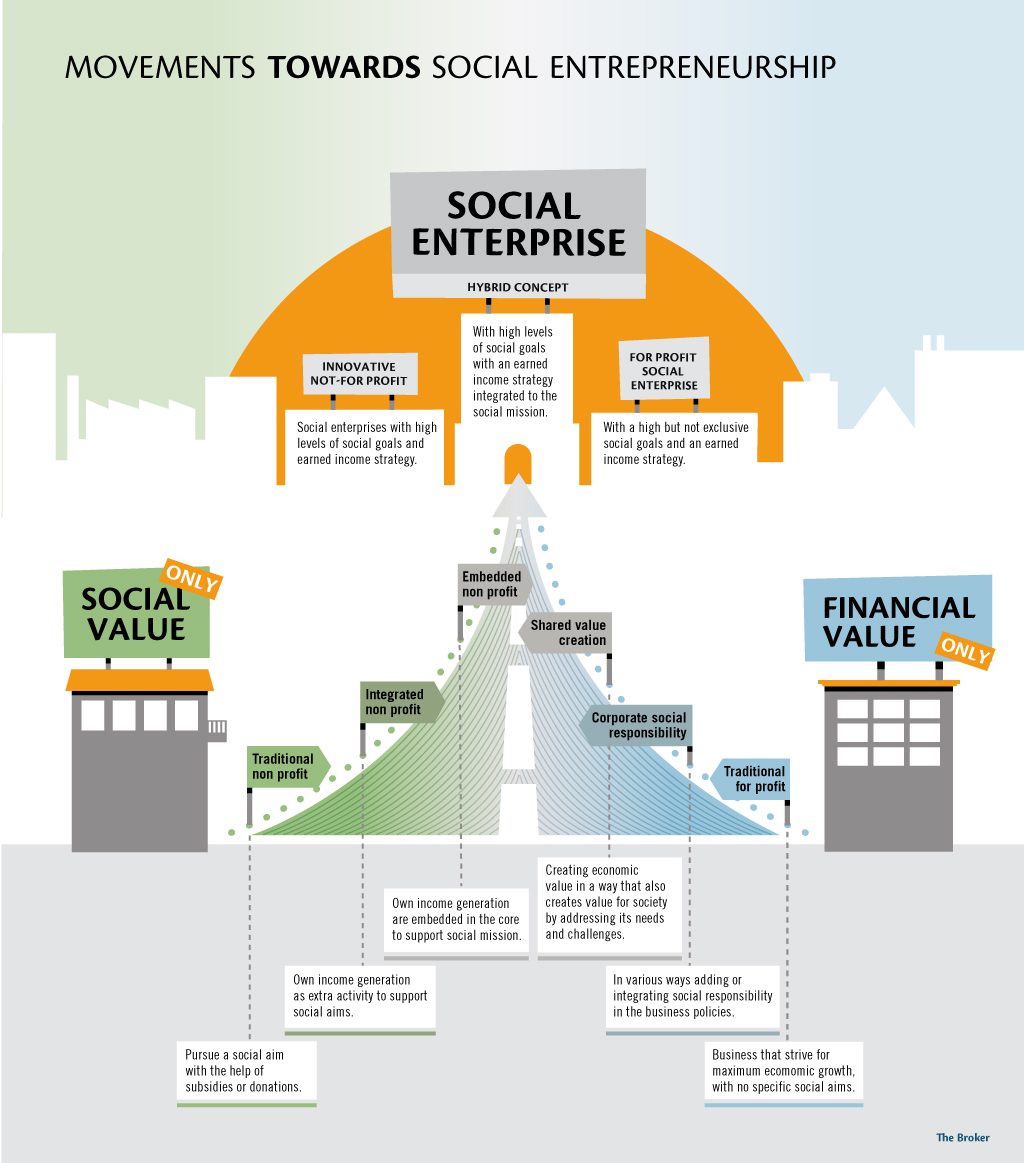

The differences in the landscape of how social entrepreneurship is defined can be linked directly to the fact that social entrepreneurship is a hybrid concept, with entrepreneurial values one side and social values on the other side. However, combining the terms ‘social’ and ‘entrepreneurship’ – which are themselves already so open to interpretation – means that any definition will result in a model that is either too vague to be meaningful or too exclusive to be accepted by a wide range of practitioners. Therefore some argue that social entrepreneurship can never be a category in itself separate from non-profit charities and for-profit business. 14

The main challenge for a social business is therefore to strike a balance between its social and financial mission. Based on a large survey of 49 countries conducted by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM), 15 social businesses can be placed on a spectrum At one end are for-profit social enterprises, with a social goal combined with a short-term for-profit strategy. Secondly, there are hybrid social enterprises with high levels of social goals and an earned-income strategy integrated in their social mission. Thirdly, innovative not-for profit social enterprises have high levels of social goals and some earned-income strategy. At the other end of the spectrum, traditional not-for–profit organizations have high levels of social goals but not necessarily an earned-income strategy. 16

Social enterprises can be for-profit, not-for profit, or at least non-loss enterprises. This may be confusing, however, as profit seeking is not their main purpose. Furthermore, a social enterprise should not only make a profit or generate income by doing good, but also should reinvest its profit and revenues to strengthen its social mission.

Framing a hybrid concept

To fit definitions and values of social entrepreneurship into a framework, experts have proposed a wide variety of specific values they see as emblematic of social entrepreneurship. They can be ordered into three dimensions: economic, social and governance (see box ‘The EMES approach to social entrepreneurship’). 17 The economic, or entrepreneurial, dimensions guarantee that there is a demand for the services or products provided and that there is an economic risk for the entrepreneur in the activities required to meet the demand. The social dimension is about a bottom-up approach to embed the activities within local communities and to avoid any profit-maximizing behaviour. The governance dimension means ensuring that decision-making is not based on capital ownership but on the voice of stakeholders who are affected by the activity and that there is an open and participatory approach.

In a perfect world social enterprises would do more than just deliver one product or service to help solve a local problem, whether they made a profit out of it or not, and seek to achieve a broader and continuous impact on society. Their production processes would have to be sustainable and socially acceptable, and their profits would contribute to this or be reinvested in a responsible way. Underlying this is the ‘double (or triple) bottom line’ perspective, which can be adopted by all types of enterprise, as well as the creation of ‘blended value’ in an effort to really balance and better integrate economic and social purposes and strategies. 18 An organization seeking a triple bottom line would, for example, offer jobs to disabled people who have been labelled ‘unemployable’, earn income by recycling, and put the profits back into the community by employing even more people. The social benefit is the meaningful employment of disadvantaged citizens, and the reduction of society’s welfare or disability costs. The environmental benefit comes from the recycling.

Social entrepreneurs, especially start-ups, cannot take all these dimensions or requirements on board at the same time. They still face many obstacles and challenges, including the lack of a legal form for social enterprises in most countries, limited access to finance, higher costs because they deliver services to remote or socially excluded communities or people with a disability, and clients who lack the financial stability to pay fees or market prices.

The EMES approach to social entrepreneurship

Economic and entrepreneurial dimensions of social enterprises

a) A continuous activity producing goods and/or selling services: Social enterprises, unlike some traditional non-profit organizations, do not normally have advocacy activities or the redistribution of financial flows as their major activity (like, for example, many foundations), but are directly involved in producing goods or providing services on a continuous basis. The productive activity thus represents the reason, or one of the main reasons, for their existence.

b) A significant level of economic risk: Social entrepreneurs assume totally or partly the risk inherent in the initiative. Unlike most public institutions, social enterprises’ financial viability depends on the efforts of their members and workers to secure adequate resources.

c) A minimum level of paid work: As is the case with most traditional non-profit organizations, social enterprises may also combine monetary and non-monetary resources, and voluntary and paid workers. However, activities carried out by social enterprises require a minimum level of paid workers.

Social dimensions of social enterprises

d) An explicit aim to benefit the community: One of the principal aims of social enterprises is to serve the community or a specific group of people. From the same perspective, social enterprises desire to promote a sense of social responsibility at local level.

e) An initiative launched by a group of citizens or civil society organizations: Social enterprises are the result of collective dynamics involving people belonging to a community or to a group that shares a well-defined need or aim. This collective dimension must be maintained over time in one way or another, even though the importance of leadership (by an individual or a small group of leaders) must not be neglected.

f) Limited profit distribution: The primacy of the social aim is reflected in constraints on the distribution of profits. However, social enterprises include not only organizations with a total constraint on distributing profits, but also those which – like many cooperatives – may distribute profits but only to a limited extent, thus avoiding profit-maximizing behaviour.

Participatory governance of social enterprises

g) A high degree of autonomy: Social enterprises are created by a group of people on the basis of an autonomous project and are governed by these people. They may depend on public subsidies but they are not managed, directly or indirectly, by public authorities or other organizations (federations, private firms, etc.). They have the right to take their own position (‘voice’) and terminate their activities (‘exit’).

h) Decision-making power not based on capital ownership: This criterion generally refers to the principle of ‘one member, one vote’, or at least to a decision-making process in which voting power is not distributed according to capital shares on a governing body with ultimate decision-making rights.

i) A participatory nature, involving stakeholder affected by the enterprise’s activities: Important characteristics of social enterprises often include representation and participation by users or customers, influence of various stakeholders on decision-making and participative management. In many cases, one of the aims of social enterprises is to further democracy at local level through economic activity.

Source: EMES report. J. Defourny, M. M. Nyssens (2013). The EMES approach to social enterprise in a comparative perspective. Working paper.

Social entrepreneurship and corporate social responsibility

Social enterprises can also be divided into two categories on the basis of what they produce.19 The first category includes social businesses which have developed a novel social or environmental service or product. For example, new technologies for alternative energy sources, redesigning appliances to integrate safety features, or creating mobile education services. Aiming to reach the largest but poorest socioeconomic groups and develop products and services to help them solve the problems they face – the aim of ‘bottom of the pyramid’ (BOP) activities – also fall into this category. 20

The second category of social businesses are those that replace existing products or services with more social and responsible choices. Whole value chains for food and other products can be made organic and offer safe and fair working conditions. In the cocoa market, Tony’s Chocolonely is a good example, 21 as it strives to make ‘slave-free’ and organic chocolate but, as a for-profit social enterprise, chooses to enter the market on a large scale.

Looking at social entrepreneurship in this way, however, can be confusing as it can also be defined as corporate social responsibility (CSR). Developing a product for the BOP market together with an NGO or working with suppliers on a code of conduct to improve working conditions does not make a company a social enterprise, as its core business is not necessarily designed around a social mission. There is, however, no clear line between where CSR stops and social entrepreneurship starts. CSR approaches range from it simply being an add-on function (such as financially supporting an NGO), to taking on a ‘cause branding’ strategy, 22 integrating CSR more into the core of policy ( ‘strategic CSR’) or adopting a sustainable mission further in their core practice (‘shared value creation’). 23 Whatever the objective, the motivation to engage in these activities is the expectation that CSR will ultimately make the enterprise more financially valuable, 24 increasing its productivity and expanding its markets.

The difference between CSR and social entrepreneurship is embedding social goals in the organization’s core objective. In a CSR approach these goals are added to the overall corporate objectives in different levels, while for social enterprises, they are the primary objective. An enterprise should therefore only be considered social if it would accept a significant reduction in its profits in pursuit of its social goals. From this perspective, a for-profit business with a CSR strategy simply does not qualify, as it might abandon its social aims if it believed its profits were at stake.

This raises another question: is the social entrepreneurial model suitable for all businesses or is it just a side project for some? Social enterprises aim to serve a direct social purpose, something that not all businesses can do. A steel plant or a haulage company, for example, may operate more environmentally and socially by adopting a CSR approach, but their main objective is not to achieve a social impact (see article ‘Social enterprises: catalysts of economic transition?‘). They would only qualify as social enterprises if, for example, they employed people who had difficulty entering the market and used steel production or haulage to achieve this in a sustainable way. A good example is the courier company Valid Express, 25 whose mission is to employ disabled people who find it difficult to get a job elsewhere. 26

Differences in welfare systems

How do social enterprises choose their missions? The opportunities social entrepreneurs see and the kind of social problems they try to solve reflect the welfare systems in which they operate. (See The Broker dossier on Social Protection.) Developing countries, for example, have no welfare systems or have systems that function badly, while the US has no publicly funded welfare system. In the UK 27 and other European countries, welfare systems are shrinking. Other factors, such as population growth, increased longevity and immigration, add complexity to welfare systems, 28 and to the legal systems underpinning them. These factors determine the way in which social enterprises emerge.

In developed countries generally, social enterprises often focus on providing services for disabled people, green solutions and nature protection, and offering open-source activities like online social networking opportunities to connect with neighbours. 29 Social entreprises in developing countries, set up by local external entrepreneurs, tend to focus more on fundamental needs like basic health care, access to water and sanitation, and agricultural activities in rural areas.

Keeping the standard high

Because there is no quality standard governing what constitutes a social enterprise, it is difficult to foresee and guarantee their socioeconomic impact. There are various impact measurement tools to help social entrepreneurs to understand and improve their impact on society (see article ‘Measuring and managing societal impact‘). Furthermore, as article ‘Doing social business right‘ shows, using a social business model is a practical way to understand and improve the way a social mission is generated and becomes part of the overall focus of a social enterprise. Some organizations, like Social Enterprise Mark, 30 an initiative from the UK to set up a certification system for social enterprises, go further in distinguishing between genuine and ‘fake’ social entrepreneurs.

In general, a certification system offer a way of strengthening the brand values, positioning and credibility of social enterprises. It would also make businesses more transparent to customers, investors and partners. A certification system has the potential not only to encourage the development of social enterprises but also persuade mainstream businesses to include social enterprises in their supply chains. On the negative side those who work on promoting social innovation might fall outside the qualification, resulting in them pushing social change further without their efforts being recognized.

The popularity of the concept of social entrepreneurship is more than just a temporary trend. It is diverse in its origins and motives, responding to what is seen government failure or corporate exploitation. However, the hybrid nature of social entrepreneurship – focusing on generating social impact through the market by using entrepreneurial values – makes it difficult to define. Creating a framework of the various aspects social entrepreneurship should ideally include helps improve understanding of how it can be supported and accelerated by policies and educational systems. 31 Social entrepreneurship must be ambitious. It must not only generate social impact, but must also be embedded in a process of continuous learning and participation by the community, with the aim to become a change agent. Revenues and profits should be largely reinvested to fulfil the social mission. Establishing this framework can bring more substance and order to the social enterprise bubble, a necessity if the concept is to be influential enough to be a serious alternative for commercial businesses and traditional NGOs.

Co-readers

Titus van der Spek, PhD candidate in Entrepreneurship and Innovation at the University of Essex.

Gerd Junne, Chairman of the board of The Network University (TNU).

Nicole Verhoeven, Co-founder and programme director of social entrepreneurship at Amsterdam Center for Entrepreneurship.

Footnotes

- Social Enterprise UK (2011) Social Enterprise Explained, for beginners, wonderers, and people with ideas, big and small. Interview with Peter Holbrook, Chief Executive of Social Enterprise UK

- According to Bidet and Eum (2011), the Social Enterprise Promotion Act of 2006 in South Korea was inspired by both the British policy and the Italian social cooperative law of 1991, which distinguishes between social enterprises providing social services and work integration social enterprises (WISEs). Bidet, E. & Eum, H.-S. (2011) ‘Social Enterprise in South Korea: History and Diversity’,2011, Social Enterprise Journal, vol. 7, n° 1, pp. 69-85.

- This school of thought has its roots in the American Social Enterprise Alliance, which defined social enterprises in the late 1990s as ‘any earned–income business strategy undertaken by a non-profit to generate revenue in support of its charitable mission’. Later they focused on all for-profit companies that pursue a social mission-driven business approach.

- Austin, J., Stevenson, H., & Wei‐Skillern, J. (2006). Social and commercial entrepreneurship: same, different, or both?. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 30(1), 1-22.

- As promoted by Muhammad Yunus (2010), founder of the Grameen Bank: ‘A social business is a non-loss, non-dividend company designed to address a social objective’.http://www.grameen-info.org/

- Jeff Trexler (2008), ‘Social Entrepreneurship as an Algorithm: Is Social Enterprise Sustainable?’ E:CO Issue Vol. 10 No. 3 2008 pp. 65-85

- www.ashoka.org

- Social innovation refers to the development of concepts and ideas that meet the social needs of people and that extend and strengthen civil society. It has commonly been used to describe how services and products can be made that can solve real problems in society, looking not only to technology as a solution but also seeking new forms of organization. The concept has been related to social entrepreneurship, but not exclusively: all kind of organizations can be involved, as social innovators are keen to build relationships between previously separate individuals and groups. Like social entrepreneurship, social innovation has many definitions. The narrow definition of solving a local problem is more related to the school of thought that focuses on social impact within social entrepreneurship. However, social innovation focusing on the actual process of innovation, how innovation and change take shape (as opposed to the more traditional definition of social innovation, giving priority to the internal organization of firms to increase productivity), can be seen much more in the school of thought focusing on change agents (sourced partly from Wikipedia).

- M. Nyssens (2006) Social enterprise: At the crossroads of market, public policies and civil society. Routledge, 2006

- http://specialistpeople.com/specialisterne/

- It is not only about creating jobs within your own social enterprise. There is an increasing commitment to include small-scale producers close to home or in other parts of the world who are normally excluded from trade relations. This inclusive business approach could be placed in this school of thought, as it focuses on including people within existing markets and trade who are normally are unable to take part in it. This inclusive business approach is not necessarily social entrepreneurship, but social enterprises could adopt this approach within their business models.

- J. Gregory Dees proposed the best-known definition of the social entrepreneur in this school of thought. He sees them as ‘playing the role of change agents in the social sector by adopting a mission to create and sustain social value, recognizing and relentlessly pursuing new opportunities to serve that mission, engaging in a process of continuous innovation, adaptation and learning, acting boldly without being limited by resources currently in hand, and finally exhibiting a heightened sense of accountability to the constituencies served and for the outcomes created.’ Dees (1998)http://www.caseatduke.org/documents/dees_sedef.pdf

- Alan Fowler (2000)

- Jeff Trexler (2008), ‘Social Entrepreneurship as an Algorithm: Is Social Enterprise Sustainable?’ E:CO Issue Vol. 10 No. 3 2008 pp. 65-85

- Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, 2009, executive report.

- If social enterprises should, at least in the long term, be financially sustainable and create sustainable social value, as stated in the section above, the first and the last category can never become real social enterprises as they lack the right motivation and organizational structure. Many businesses will, however, call themselves social enterprises while just seeking opportunities to make money out of a single social purpose without a long-term social mission that integrates sustainable production systems through the whole value chain, allowing communities and other stakeholders to participate, or reinvesting their profits in society. Many start-up social entrepreneurs prefer to be more profitable in the short term and later use their financial sustainability to focus gradually on their social mission. But others will choose to be more dependent on grants in the short-term to ensure they do not drift away from their social mission. Although neither are perfect, they can both be considered social enterprises as the motivation and drive to aim for a social impact is an important factor within social entrepreneurship.

- Defourny & Nyssens, EMES report, 2013

- Bull, Michael. “Challenging tensions: critical, theoretical and empirical perspectives on social enterprise.” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research 14.5 (2008): 268-275

- W. Verloop, ‘Het kan, sociaal, groen en een boterham verdienen’, De Volkskrant, 23 September 2013

- C.K Prahalad and S. L. Hart, 2001,The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid.

- http://www.tonyschocolonely.com/

- Avon Cosmetics allies itself with the cause of raising breast cancer awareness. Cause branding provides needed support for the worthwhile social project and at the same time benefits the profitability of the business, partly by encouraging loyalty among customers and employees.

- http://hbr.org/2011/01/the-big-idea-creating-shared-value/

- A. Smit, 2012, How to valuate a social enterprise, Business School Nederland

- http://www.validexpress.nl/

- Interestingly, Valid Express, a financially sustainable social business, was taken over by large commercial courier company PostNL in 2012.

- Amin, Cameron, and Hudson (2002) Review of The Social Economy.

- E. Chell, K. Nicolopoulou & M. Karataş-Özkan (2010) Social entrepreneurship and enterprise: International and innovation perspectives. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development: An International Journal, volume 22, Issue 6

- T. Ellis, (2010) The New Pioneers

- Qualification for the Mark: Your company must: 1. have social and/or environmental aims 2. have its own constitution and governance 3. earn at least 50% of revenue from trading 4. spend at least 50% of profits on social/environmental aims 5. distribute residual assets to social/environmental aims if dissolved 6. demonstrate SOCIAL VALUE.http://www.socialenterprisemark.org.uk/

- Two trends can be distinguished as a reaction to the confusion this hybrid concept of social entrepreneurship causes. First and most common is to specify and categorize social entrepreneurship more and more, with the aim to build a separate sector of social entrepreneurs. The other is not to see social entrepreneurship as a separate sector but as a transitional form. It brings together values that should not have been torn apart. As its lessons are learned within mainstream business, social entrepreneurship can gradually disappear (see in this dossier ‘Social enterprises: catalysts for economic transformation?’)