The Ukrainian Euromaidan protests started on 21 November 2013 and culminated in the overthrow of President Viktor Yanukovych at the end of February 2014. As with other mass uprisings, it brought together, to the streets and squares, people with different grievances. However, those with the least progressive grievances significantly shaped the protests and, in the end, benefited the most from them.

Yanukovych’s refusal to sign the EU association agreement with Ukraine provided the initial push for the protests, which were largely misrepresented by the majority of protesters as the first step towards EU membership. After the still under-investigated violent dispersal of the week-long protest camp at Kiev central square by ‘Berkut’ riot police on 30 November 2013, the movement gained momentum with hundreds of thousands of people joining the protests. The protesters were not only outraged by the police brutality, but had started to demand the resignation of the government.

The grievances that shaped the Maidan protests

As in many other social movements, the elites were crucial to the success of the protests. The opposition oligarchs were fed up with the monopolization of power by Yanukovych’s ‘family’ and feared that he would steal the coming presidential elections in February 2015, as he had done in 2004 triggering the ‘Orange Revolution’[i]. To date, there has still not been a thorough investigation into the financial support for the mass protests, which lasted three months, but the scale of crowdfunding was seemingly high. However, the opposition leaders emerged as the political representatives of the movement, negotiating with President Yanukovych on the protesters’ behalf and assuming power after he was overthrown. The Western Ukrainian local councils controlled by the opposition parties also defended the Maidan protesters from repression and provided symbolic and infrastructural support to local camps, as well as for the mobilization of people to the capital.

The Western-funded NGO activists, with their typical agenda of anti-corruption, transparency and (neo)liberal reforms, were also important in supporting the mobilization. The widespread corruption in public institutions – from kindergartens to the presidential office – was among the most important grievances driving the Maidan, although the average protestor was not as concerned with transparency to facilitate foreign investment, as they were with the social inequality resulting from the corruption of top-officials.

The Maidan was also a protest against real and imagined Russian interference in Ukraine’s politics. Both Russia and the EU had imposed exclusive demands on Ukraine with their competing free-trade zones. The choice of EU association was a choice against Russia, and vice versa. Ukrainian nationalists saw Russia as the historical enemy; for more liberal protesters the choice was between ‘European values’ and an orientalist utopia, as opposed to their increasingly authoritarian and conservative ‘Eastern neighbour’.

A movement with nationwide support?

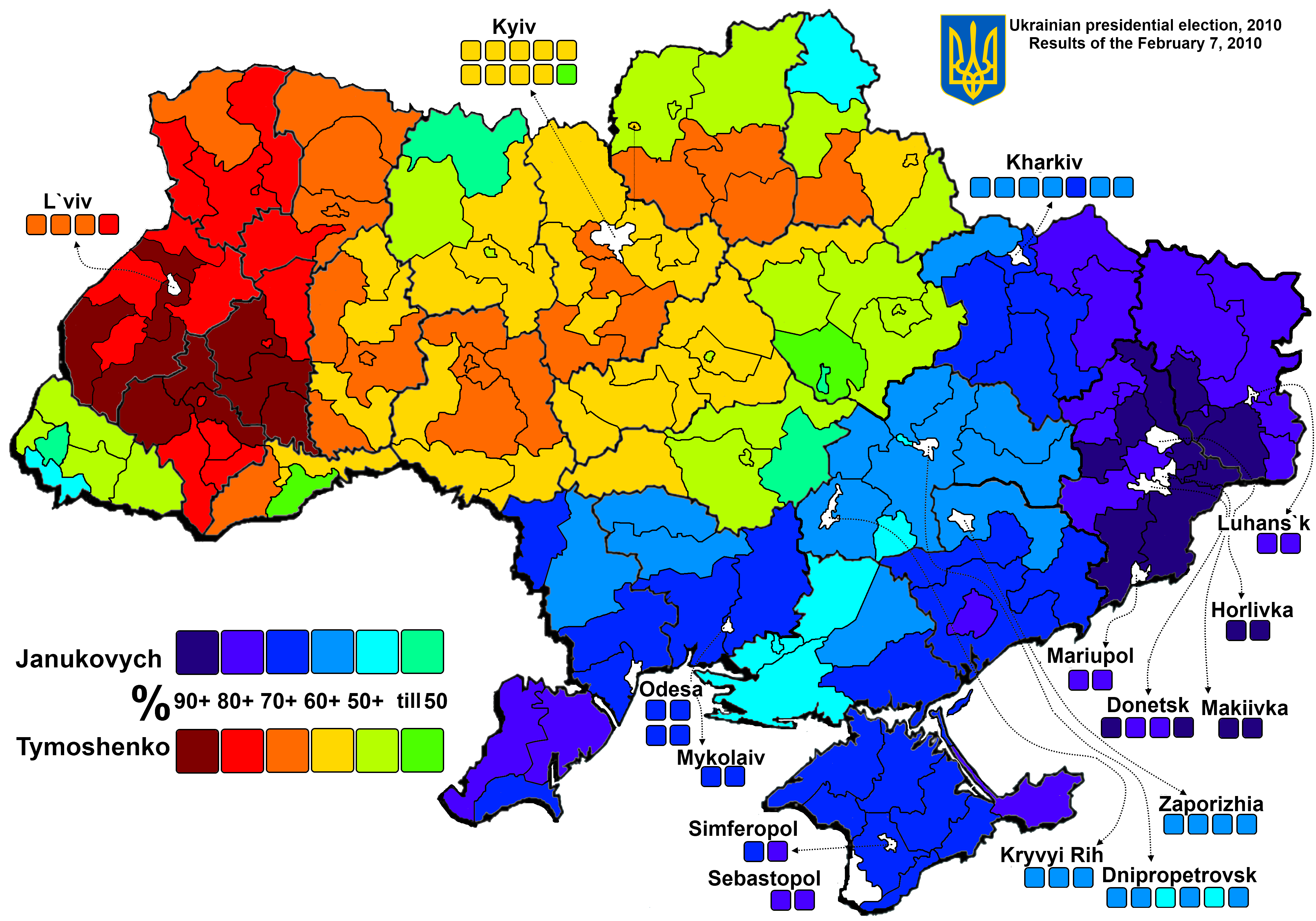

The polls conducted in the Kiev camp in January 2014 showed a shift in the protesters to poorer, less-educated participants from small towns in Western and Central Ukraine, compared to the predominantly middle-class protesters from the capital seen in December 2013, whose number decreased after the violence started. One thing about the social basis of the Maidan was clear: support for the Maidan was heavily split between Ukraine’s regions. However, Maidan supporters seem to be unwilling to recognize this fact, as it goes against the official narrative about the nationwide ‘Revolution of Dignity’.

The protests had never enjoyed majority support in the predominantly Russian-speaking south-eastern Ukrainian regions, which voted for Viktor Yanukovych in the 2004 and 2010 elections against the candidates supported by the majority in the Ukrainian-speaking parts of the country. Although some people from Kharkov and Odessa, and even Donbass, came to support the Maidan protesters in Kiev, the local protest events in south-eastern Ukraine usually gathered less than 100 people. At the same time, the crucial role of the protests in Western Ukraine is often overlooked in the Kiev-focused narrative about the Maidan. Generally, these protests were no less massive and no less radical than the protests in the capital.[ii] And, it is in Western Ukraine, not in Kiev, that Yanukovych effectively lost power first.

The role of the far right

Despite the fact that most of the Maidan protest events were peaceful, the scale of the violence had not been seen in Ukraine for more than half a century. The violence was provoked by the clumsy and inconsistent repression of the protesters. However, subsequent investigations under the post-Maidan government that were either executed incompetently or sabotaged have led some scholars to believe that some of the messiest events could be ‘false flag’ operations, specifically contrived to escalate the violence and prevent any compromise with Yanukovych.[iii] As the protests went on, radicalism grew from the barricading and occupation of state buildings, to massive clashes with the police and, finally, to the seizure of arms in the last days. However, no serious labour strike happened in support of the Maidan, due to both the weakness of organized labour in Ukraine and the distance of the oligarchic and (neo)liberal opposition from the social-economic struggles of regular Ukrainians.

As the violence escalated, the far right played the more visible and leading role. Although they were not the most numerous, they were clearly the most active and organized collective agents in the Maidan protests.[iv] They joined the Maidan at the very start, although they cared not so much about liberal ‘European values’ (which they did not believe in anyway), but about a nationalist revolution, for which they had been preparing for a long time. From the very beginning, the far right mainstreamed their slogans – which were derived from the nationalist guerrillas during WWII, who were glorified as heroes in Western Ukraine, but despised by the majority in south-eastern Ukraine as Nazi collaborators – among Maidan participants. Now almost official in Ukraine was the greeting ‘Glory to Ukraine! Glory to the heroes!’, which was used exclusively in the nationalist subculture before the Maidan.

Despite some modest criticism of the far right by the liberal wing of the Maidan movement, there has never been a serious attempt to break with them. Such a split would have postponed the overthrow of Yanukovych, but it could also have given the movement more time to build a truly nationwide movement against the regime, incorporating majorities in Eastern and Southern Ukraine. By necessity, such a movement would have been devoid of divisive radical nationalism and, instead, could have been based on social-economic grievances against the corrupt elite. Nevertheless, this possibility was unlikely because of the oligarchic nature of the opposition parties, the neoliberal-nationalist orientation of civil society, and the weakness of the Ukrainian left and labour movement, while the major left-wing force – the Communist Party of Ukraine – was a de facto part of the governing coalition under Yanukovych.[v]

Revolution or transfer of power?

By the end of February 2014 Western Ukraine was close to a classical revolutionary ‘dual power’ situation, with the protesters seizing arms, usually without serious resistance from law-enforcement. On 21 February Yanukovych escaped from Kiev, gradually losing the support of the riot police and his own party after the last wave of violence. He also failed to mobilize south-eastern elites in his defence, which later opened the road for Russia and pro-Russian separatists to capitalize on the grievances and fear of the Donbass population against Ukrainian radical nationalists and the new post-Maidan government.

Three-and-a-half years later, the former Maidan supporters are no doubt disappointed with the results of the protests. The post-Maidan government has very few real achievements to show the Ukrainian people, except for the recently-implemented visa-free regime with most EU countries. Ukrainian economy is only now beginning to grow very slowly, after a 16% decline in GDP in 2014–2015. The problems with top-level corruption persist. The EU membership option is closed and the deep and comprehensive free-trade zone with the EU is not benefiting higher added-value industries in Ukraine. The IMF has demanded austerity reforms, which has increased the burden on the poorest layers of Ukrainian society.

Of course, the Russian government has added much to Ukraine’s current problems, attempting to prevent the spread of the revolution to its own country and draw a red line against pro-Western expansion. At the same time the Ukrainian president, Petro Poroshenko, is using national-patriotic outrage against Russia to consolidate his power. The authorities, on the one hand, and the strengthening far right, on the other, harass, ban and destroy the opposition parties, protests and media, gradually establishing nationalist hegemony in the public sphere.

But how much different would Ukraine be now if Russia had not annexed Crimea and supported pro-Russian separatists to establish puppet states in Donbass? Quite probably many of the people killed in the shelling would still be alive and living in their homes. This is important. But would the Maidan, with its divisive agenda, have pushed Ukraine to a democratic breakthrough? Would peace, tolerance and pluralism have prospered in Ukraine despite the intensified regional cleavages and mutually-reinforcing nationalist mobilizations? Would the far right paramilitaries have disarmed and disbanded themselves? Would Maidan opponents have remained non-violent? Would the pro-Maidan oligarchs have stopped corruption – which gives their businesses a crucial competitive advantage? Would Ukraine have gained clear EU membership prospects? Would there be more social equality without any significant political force capable of articulating a progressive social-economic strategy and uniting Ukrainians under this agenda? Many people in Ukraine, and beyond, genuinely held these hopes; hence, the danger of wishful thinking is one of the most important lessons of the Euromaidan.

References

- De Ploeg, Chris Kaspar. 2017. Ukraine in the Crossfire. Atlanta, GA: Clarity Press; Wilson, Andrew. 2014. Ukraine crisis: What it means for the West. 1St Edition. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Ishchenko, Volodymyr. 2016b. ‘Far right participation in the Ukrainian Maidan protests: An attempt of systematic estimation.’ European Politics and Society 17 (4): 453–72. doi:10.1080/23745118.2016.1154646.

- Katchanovski, Ivan. 2015. ‘The ‘Snipers’ Massacre’ on the Maidan in Ukraine.’ https://www.academia.edu/8776021/The_Snipers_Massacre_on_the_Maidan_in_Ukraine.

- Ishchenko, Volodymyr. 2016b. Op cit.

- Ishchenko, Volodymyr. 2016a. ‘The Ukrainian Left during and after the Maidan Protests.’ https://www.academia.edu/20445056/The_Ukrainian_Left_during_and_after_the_Maidan_Protests.