With the recent onset of joint assessments, planning and execution of interventions in international cooperation in fragile or conflict-affected states, the question arises of how to facilitate cooperation between different institutions and organizations. Management theories from the corporate sector can provide some interesting insights and possible solutions, as they address many of the problems that actors engaging in comprehensive approaches face today. A multi-stage networked organizational structure in particular can provide the flexibility and inclusiveness that collaborative efforts for conflict resolution need.

The roots of conflicts are almost always complex. In recent years, a consensus has started to emerge on the most effective way to integrate interventions by different actors in fragile or conflict-affected countries (FCAS). These interventions ultimately aim at creating peace but depart from different theories of change. A multidisciplinary approach, combining military, diplomatic, humanitarian, developmental, security and economic interventions, is now seen as a requirement for creating sustainable peace, as there can be no peace without development and no development without security. To ensure the effectiveness of this approach it is important that the multiple international actors involved in these peacebuilding interventions increase the effectiveness of their interdependent actions in conflict settings by trying to maximize coherence and by seeking synergy in what has come to be called a comprehensive approach.

Organizing organizations to work comprehensively

Since these multidimensional interventions in FCAS are increasingly becoming the norm, different ways of implementing a comprehensive approach have been surfacing. Approaches that have been developed so far vary in their degree of coordination (from competition to full integration) and coherence (between departments, ministries or international actors, most notably the EU, UN and NATO), as an important work in conflict management by Coning and Friss points out.1 The goal of these different comprehensive approaches is to bridge existing policy and institutional gaps that are impeding collaborative efforts by the international community across the crisis management spectrum. However, in order to achieve this complementarity of dimensions to peacebuilding interventions, there has to be a consensus between the collaborating actors on the approach to planning and execution . Which is why the different priorities of actors in national or international contexts have resulted in different types of comprehensive approaches.

The planning and execution of a comprehensive approach passes through a series of phases: from orientation, analysis and assessment, options for action, planning and preparation, and execution to evaluation. It has different organizational and context perspectives (in the field between local and international actors, at the international level between all the international players, and at a national level of one of the countries contributing to an intervention). Coordination and collaboration among the multiple entities in these different contexts is challenging, particularly so in the early phases. And when creating a new organizational format to facilitate this type of collaboration, actors are faced with various additional problems. Like how to design and implement a format that leads to action in an early phase when there might not be political consensus, or a lot of media attention. Or how to create an organization at national level that can adapt in a flexible way to a range of emerging and/or ongoing crisis contexts while still offering sustainability and continuity.

Management literature and planning for the comprehensive approach

Experiences from the corporate sector reveal that fifty to seventy percent of partnerships fail prematurely. While partners often have goals in common, they also have individual objectives that do not necessarily complement one another. In addition, the partners may have a variety of differences that present an obstacle to effective collaboration. Within the current debate on organizational management, a “networked organization” is generally considered to be the most appropriate structure for this kind of coordination among multiple organizations.2

Networked Organizations

The term “networked organization” here refers to organizations that rely on the emerging dynamics of collaboration instead of formal hierarchical structures. An important author in this debate is Herranz, who distinguishes three archetypical strategic orientations of a such an organization: bureaucratic (such as governmental networks and public agencies), entrepreneurial (such as private companies) and community (such as volunteer organizations or neighbourhood associations). In addition to the strategic orientation, Herranz also sketches a passive to active continuum of four archetypical network management regimes, as viewed in the table below:

Table 1. Suitability mapping of network management regimes on strategic orientations, as proposed by Herranz

| Network management regime | ||||

| Strategic orientation | Reactive facilitation | Contingent coordination | Active coordination | Hierarchically-based directive administration |

| Bureaucratic | X | x | ||

| Entrepreneurial | x | X | ||

| Community | X | x |

• Reactive facilitation is the most passive form where network coordination relies on social interactions rather than procedural mechanisms or financial incentives. The overall behaviour of the network emerges from interaction rather than being deliberately planned.

• Contingent coordination applies some influence to guide network behaviour while reliance on emergent behaviour is still quite high.

• Active coordination implies a more deliberate design of the network, including its constituent partners as well as the interaction and incentive mechanisms among the partners.

• Hierarchical-based directive administration implies coordination with authoritative mechanisms rather than reliance on social or incentive mechanisms.

However, while they share many similarities, there are also notable differences between the corporate and the comprehensive approach contexts. Actors in the corporate sector with comparable strategic orientations are often driven by market dynamics to work together, for example because they can reduce the per unit cost if they produce in larger quantities. Actors in a comprehensive approach, on the other hand, have different funding sources and different theories of change that underpin their interventions. For example, while actors from a defence organization and aid agency might both initially view the presence of drug trafficking organizations as a problem for the security of a region, explaining their presence in terms of security or social issues, ineffective policing or a lack of economic opportunities, will lead to different interventions with often conflicting priorities and interests. This can result in ineffective or even failed interventions, especially when looking at the longer term. Any solution to the problems of planning an effective comprehensive approach should therefore consider multiple priorities and interests, ideally by using the strengths of each actor to come to an integrated intervention. Thus, integrating multiple perspectives at an early stage of identifying context and priorities is clearly essential for the design of successful interventions based on a comprehensive approach.

Because of the specific demands of a comprehensive approach – namely the requirement of early integrated analysis by a multitude of parties while leaving room for a quick response in the face of a crisis situation – there is a need for different management regimes at different stages of planning. Thus to apply the theory of network management to this early stage, we distinguish four levels of coherence in networked organizations;i three of which have already been described, i.e. international-local, inter-agency (between international community actors) and whole-of-government. The fourth one is intra-agency. Within these different coherences, relationships between actors may vary from competitive, coexisting, coordinating up to integrated or united. The tricky point now is that in the case of whole-of-government and intra-agency relationships, one network management regime will fit. But that for the international-local and inter-agency relationships there is no longer one network management regime that fits, given the mix of organizations with their varying strategic orientations. The result is the introduction of a multi-stage networked organization.

Planning the comprehensive approach in a multi-stage networked organization

There are several stages of planning in a multi-stage networked organization designed for intervention planning in the context of a comprehensive approach. Each stage has its own types of collaboration and styles of management. The first stage consists of building relationships in order to share knowledge and expertise among a large group of stakeholders (ranging from, for example, think-tanks to NGOs) in a learning network. This type of working relationship would be best served with a management regime based on contingent coordination – so as to be flexible in facilitating knowledge sharing. After this phase, a specific group of learning network members can give input – using their expertise and analytical capacities – to the government agencies that are developing a shared analysis of the situation and they can contribute to determining strategic options for action. In this phase, the organization could benefit from a management style more based on an active coordination regime, in order to come up with concrete suggestions for policymakers. By using such a multi-staged process, a shared understanding of a crisis situation is created so that at a later stage the actions of different actors are sure to complement each other, rather than overlap or even counteract the different efforts.

A multi-stage networked organization

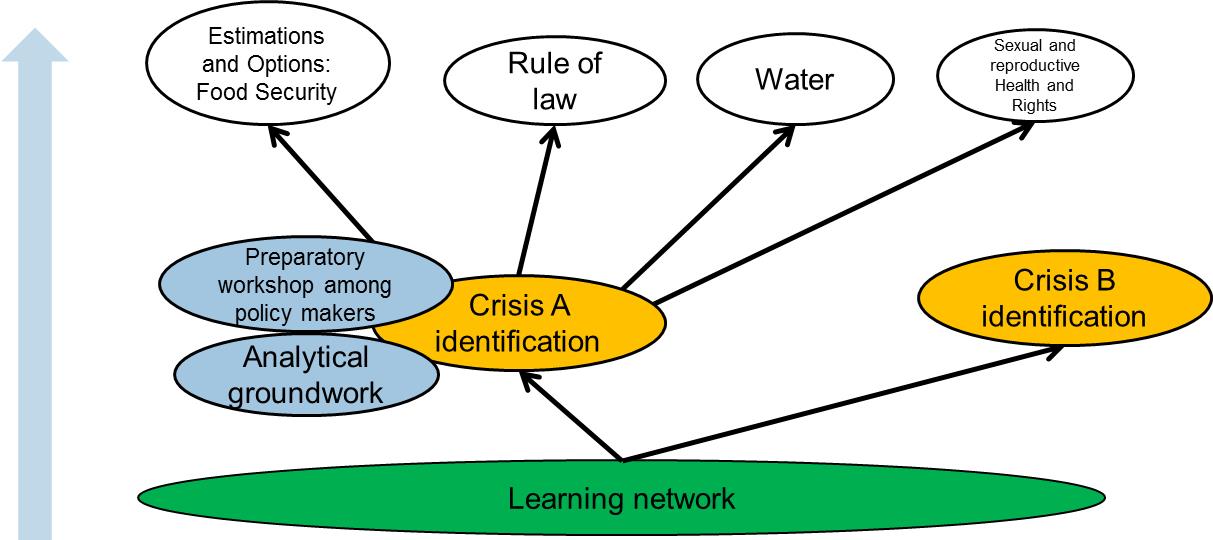

A multi-stage networked organization for a comprehensive approach ideally consists of three stages of collaboration: 1) a learning and research network, 2) a crisis identification group and 3) estimation and options groups.

The first stage consists of building the relationships between actors in order to share knowledge and expertise among a large group of stakeholders. In the second stage, stakeholders can join smaller subgroups focused on a certain crisis area in order to create a shared awareness of the intervention context and to define different policy options for this area. In this multi-stage network, the different focal hubs can exercise different network management regimes: from reactive facilitation in the first stage up to active coordination.

First initiatives to test such a multi-stage networked organization have been made for a strategic assessment of the situation in Somalia by the Dutch Ministries of Defence and Foreign Affairs.3 The Netherlands has a strong ambition to further develop the what it calls the integrated approach, as is evidenced by the recently published Guidelines on the Integrated Approach.4 And by combining the insights described above, the pilot attempted the integration of multiple actors’ perspectives in different stages of the intervention planning in order to ensure that information sharing among actors led to optimal identification of options for effective intervention.

To conclude, a comprehensive approach is considered the most effective way to tackle the complex and multidimensional roots of conflict and to create lasting peace in FCAS. Contemporary management theory provides new insights and possible solutions to the organizational challenges that are inherent to the comprehensive approach. Organizations that differ widely in their strategic orientation have to work together comprehensively along the various phases of the crisis spectrum: assessment, planning, execution and review of interventions. The multi-stage networked organization is an example of a promising adaptive and inclusive application aimed at tackling these challenges along the different phases, but its application is still in its infancy and requires further research and validation.

Footnotes

- Coning, C. de & K. Friis. 2011. Coherence and Coordination: The Limits of the Comprehensive Approach, Journal of International Peacekeeping 15 (1/2): 243-272.

- Herranz, J. The multisectoral trilemma of network management, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18: 1-31

- Homberg, M.J.C. van den, Pieneman, R.B.J., Kuijt, J. van de, Berg, P. van den 2014. Effectiveness of a Multi-Stage Networked Organisation for Early Integration of Multiple Perspectives on Emerging and Future Crises, NATO Human Factors and Medicine Panel 238 Symposium Effective Inter-agency Interactions and Governance in Comprehensive Approaches to Operations, Stockholm, Sweden on 7-9 April 2014

- Government of the Netherlands, Leidraad geintegreerde benadering: De Nederlandse visie op een samenhangende inzet op veiligheid en stabiliteit in fragiele staten en conflictgebieden