Following elections in March 2021, the Netherlands is still awaiting the formation of a new government. This article takes a closer look at recent trends in Dutch development cooperation policy and the choices that lie ahead to strengthen its relevance and effectiveness. It examines what could and should be in store, by asking four key questions: ‘how much?’, ‘what?’, ‘where?’ and ‘how?’. In terms of ‘how much’, the Netherlands must find a concrete path back towards spending 0.7% of its GNI on aid. In answer to the ‘what?’ and ‘where?’, the challenge is to stick to chosen focus areas. And in reply to the very important but often neglected ‘how?’, a new government would do well to dust off a 2017 OECD Peer Review Report and put to practice its recommendations to strengthen local ownership and reduce fragmentation.

A quick word on post-pandemic SDG-action

Even before the world came down with COVID-19, reaching the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030 was becoming increasingly unlikely. The pandemic delivered another major blow, pushing an additional 100 million people into extreme poverty. And prospects are not good: Recovery in developing countries is hampered by poor access to vaccines – meaning that the virus will likely keep resurging – and a lack of fiscal capacity to boost their economies. The IMF estimates that by 2024, rich countries will have caught up with or even exceeded their pre-pandemic growth trajectory, while developing economies are expected to be 5.5% smaller. Meanwhile, the effects of climate change are increasingly being felt, and again it is the group of low-income countries that is hit hardest. Action is required on many fronts. Not least by creating a fairer global trading and financial system, among others through better agreements on sharing vaccine technology and closing tax loopholes.

In addition to such measures an increase in development finance, in the form of Overseas Development Assistance (ODA), will also be essential to jointly tackle the myriad challenges facing low-income countries. Particularly in the context of worsening climate change, failure to do so could fuel conflict and political instability, which would in turn complicate global efforts to reach the SDGs. Besides increasing the level of ODA-resources, it is crucial to improve the effectiveness of expenditure and implementation. Increased collaboration, finding synergies and complementarities between different agendas, and finding ways to effectively link global agendas and local contexts will prove highly important.

How much: From gradual stagnation to bounce-back?

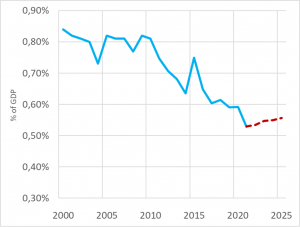

At present, total Dutch ODA spending in the 2022 budget is foreseen at EUR 4.78 billion, equivalent to 0.53% of GNI, well short of the commitment to allocate at least 0.7%. This figure is hardly any improvement compared to the historic low of 2021 (see Figure 1), consistent with the gradual decline of ODA spending since the first government of Prime Minister Mark Rutte took office in 2010, when it stood at 0.8%. It is worth recalling that this 0.8% of GNI was reached consistently throughout the 2000s as a result of a broadly shared commitment to honour the 0.7% norm, adding a further 0.1% for environment-related ODA. In the years following the 2009 Copenhagen climate summit, however, the Netherlands completely let go of the additionality of climate finance to regular ODA. This is, to say the least, ironic, as it was at Copenhagen that the pledge was made of working towards $100 billion in annual additional climate finance from 2020 onwards. By including mobilized private finance, the Netherlands claims to be fulfilling this commitment. It is clear, however, that it is not additional to ODA: In 2020, public climate finance represented 0.08% of GNI – but this is included within the total ODA spending of 0.53%.

Thanks to a growing economy, Dutch ODA spending has remained relatively stable over the past decade in absolute terms: fluctuating around EUR 4.5 billion (see Figure 2). Although the 2022 budget will most likely continue to secure the Netherlands a place among the top 10 global donors, its relative significance in global ODA spending has gradually eroded. Whereas Dutch ODA spending, in absolute terms, was consistently 50% higher than Sweden’s in the 2000s, today Sweden, a much smaller economy, outspends the Netherlands.

Figure 1: The Netherlands ODA as a percentage of GNI

Source: Author, based on budget documents of Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Figure 2: The Netherlands ODA in EUR millions

Source: Author, based on budget documents of Ministry of Foreign Affairs

So, what is next? The budget for 2022 was prepared by the ‘demissionary’ four-party coalition government that took office in 2017 and is therefore mostly a continuation of existing policy. Even though elections took place in March 2021, a highly fragmented political landscape and a complex set of interrelated political blockades have resulted in a long delay to the actual start of negotiations for a new government. Ultimately, in September, the same four parties that make up the current governing coalition agreed to sit down to negotiate a new agreement. This does not mean, however, that no change is possible in terms of ODA spending. On the one hand, there could be renewed downward pressure, as fiscal conservatives worry about higher public debt following the covid stimulus packages. On the other hand, the electoral gain of the liberal-progressive D66 party, and the fact that it conceded to these negotiations at the expense of their preferred option of including left-wing parties in the talks, has strengthened the party’s negotiating position. D66 leader Sigrid Kaag, the former minister for trade and development, could use this to secure a gradual but structural increase in ODA, back in the direction of 0.7%.

What & Where: Looking for Focus

Unfortunately, all too often the debate on development cooperation remains limited to the amount of spending and the percentage of national GNI spent on ODA. The importance of ‘how much’, however, should not come at the cost of asking the questions ‘what?’, ‘where?’ and ‘how?’.

Thematic focus areas

Successive ministers for development cooperation have highlighted the need for more thematic and geographic focus. Yet, predictably, every new minister chooses a slightly different focus, so that the end result is the opposite. This is highly inefficient, as entering a new focus area requires large investments in terms of knowledge acquisition and network building, while leaving an area means that the results of previous investments are essentially thrown away. In the early 2010s, therefore, the government decided to restructure Dutch development policy around four thematic areas: (i) sustainable economic development, trade and investments; (ii) sustainable development, food security, water and climate; (iii) social progress; and (iv) peace, security and sustainable development. These areas remain so broad, however, that they still allow for a wide range of sub-areas1 and continued changes in thematic focus at that level. It remains to be seen whether a new minister in a new government can resist the temptation of adding thematic focus areas to the list and at the same time dropping existing ones in order to ‘keep focus’.

Geographic focus areas

A similar dynamic can be observed regarding geographic focus. Under Minister Kaag, Dutch policy moved away from the term ‘partner countries’ and instead opted for ‘focus regions’.2 While in some cases, such as Mali, Ethiopia or Uganda, this simply meant a relabelling exercise, it also involved very real shifts. Burkina Faso and Niger, which in the recent past hardly received any Dutch development aid at all, today feature among the most prominent recipients. In the Middle East and North Africa, countries like Jordan, Egypt and Tunisia, were added to the list of countries receiving considerable resources. On the other side of the spectrum, the development relationship with Indonesia, Ghana and Rwanda is being phased out. Resource flows to these countries have been reduced dramatically. Another group of countries finds itself in limbo: Burundi, for example, is still a partner country, but as it is not located in a focus region may be unsure what to expect in terms of future Dutch commitments. Bangladesh, Benin and Mozambique are no longer partner countries and are not located in a focus region either, yet still receive considerable resources. The overall result, instead of more focus, is geographic fragmentation; a trend that is particularly visible in budget allocation: In 2018 a total of 15 countries received more than EUR 5 million in bilateral resources at country-level; in the 2022 budget this has risen to 21 countries.3 Furthermore, in practice, the so-called focus regions do not seem to have prime focus: combining centrally managed and delegated (to country-level) resources, the share of ODA spending on the focus regions went from 26.0% in 2019 to a planned 26.6% for 2022.

In terms of thematic as well as geographic focus, there is clearly some work to be done for the prospective minister of development cooperation. When it comes to the geographic scope, some questions will demand immediate attention: How will the relationship with countries in the new focus region of the Middle East and North Africa evolve? What to do with the countries in a limbo position? The answer to these questions depends in part on the answer to the ‘how much?’ question. A growing ODA percentage and a growing economy would mean a substantial increase in resource availability, which could open up the possibility of maintaining or intensifying the relationship with all current recipients. At the same time, it is important to keep some flexibility to adjust to in-country political developments. It is often in the wake of unforeseeable political events, such as a certain election outcome or the downfall of an authoritarian regime, that a quick disbursal of resources can have a lasting impact.

How: The neglected question

The ‘how much?’, ‘what?’ and ‘where?’ questions of development cooperation lend themselves quite well to critical opinions and discussions: One could debate why, as a rich country, we must fulfil our moral duty; why a certain theme, like climate or women’s rights is too important to be ignored; why a specific region or country deserves our special attention. Such discussions become more difficult, however, where the ‘how?’ question is concerned. Here, different views are not easily captured in catchy slogans and a certain level of technicality cannot be avoided. As a result, it often receives much less attention.

The avoidance of the ‘how?’ question in public debates, while understandable, is highly unfortunate. Over the past 60 years, an enormous amount of evidence has been generated on what works and what doesn’t. One major overarching lesson is the importance of local ownership. Development simply cannot be exported, imposed or driven by outside experts. Another is the importance of harmonisation of development efforts. A plethora of different donors, NGOs and multilateral organisations all intervening in a specific sector in a specific country through their own programmes in a disjointed manner is ineffective and can even be counterproductive. These two lessons are very much related. Fragmentation driven by a wide range of different outsider agendas undermines local ownership. Conversely, where local ownership is put centre stage by all actors, greater harmonisation is likely.

In the 2000s these key insights were very much in swing in the global development community, culminating in the Aid Effectiveness Agenda and a range of joint declarations, notably the Paris Declaration (2005), the Accra Agenda for Action (2008) and the Busan Partnership Agreement (2011).

To be able to seriously put these ideals of local ownership and harmonisation to practice, a greater share of development finance needs to be programmed and managed at country level, not in far-away donor capitals. Several more recently developed concepts and theories, such as ‘Thinking and Working Politically’ and ‘Problem-Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA)’, also point in this direction. These ideas emphasize the importance of reasoning from the local political context and a deep contextual understanding of the way in which existing systems function and the specific problems that need to be tackled.

Dutch ODA and Aid Effectiveness

Given the aid effectiveness declarations of the 2000s and the recent insights on the importance of local context, let’s now take a look at the extent to which Dutch development cooperation has taken these principles on board.

A useful starting point is the 2017 OECD-DAC peer review, which examines the Dutch development policy. It found that ‘the context and preferences of partner countries are not identified as the point of departure’ and that ‘budgets are increasingly managed from the Netherlands, with limited opportunities for national governments to input into decisions’. It also observed that ‘only 10% of Dutch ODA is channelled through embassies’ and that ‘more and more funding is directed to instruments and tenders originating from The Hague’. This centrally-driven tender approach, concludes the OECD, ‘comes at the expense of commitments to development effectiveness’. Its recommendations included to ‘increase the use of or strengthening of partner country systems’ and to ‘enhance the role of embassies, including through delegated funds’.

The findings of the OECD review clearly show that there is much to be gained with regards to harmonisation, local ownership and context-specific programming. Unfortunately, however, Dutch policy documents hardly ever refer to the OECD peer review and its recommendations. Moreover, the budget figures (see table 1) do not suggest that the key OECD recommendations are being seriously implemented.

Table 1. Centrally managed vs delegated resources, as % of ODA spending

| 2019 (realised) | 2020 (realised) | 2021 (planned) | 2022 (planned) | |

| Delegated to country-level (embassies) | 10.8 % | 10.6 % | 12.4 % | 11.8 % |

| Centrally managed by BHOS Ministry4, region-specific | 21.6 % | 21.3 % | 20.7 % | 18.6 % |

| Centrally managed by BHOS Ministry, no geographic designation | 29.5 % | 32.8 % | 32.1 % | 35.5 % |

| ODA on budgets of other ministries | 38.0 % | 35.4 % | 34.8 % | 34.1 % |

Source: Author, based on budget documents of Ministry of Foreign Affairs

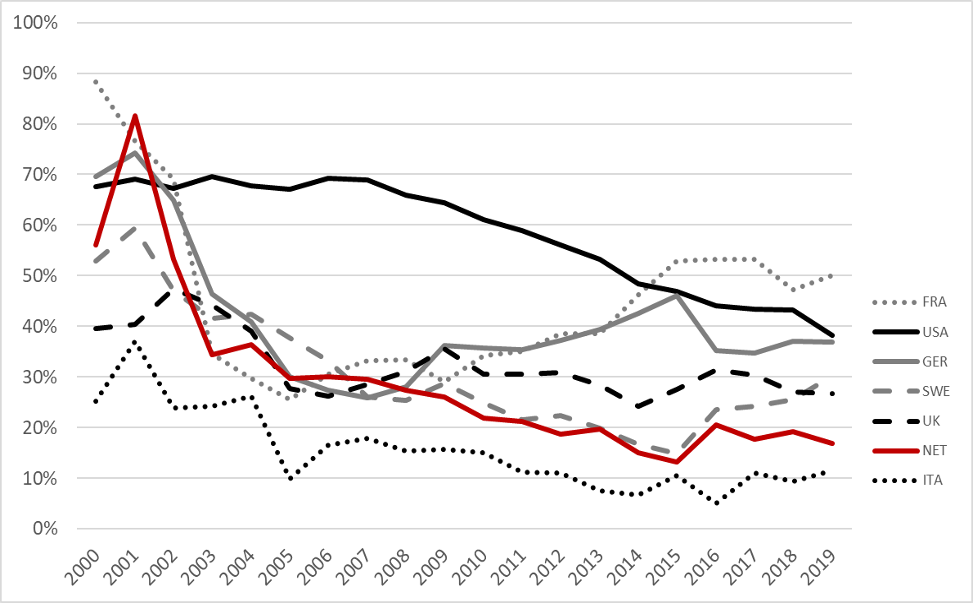

Most telling is the apparent trend of low and declining use of delegated resources – managed by embassies at country-level – and region-specific resources. Although not directly comparable due to evolving budgetary categories, delegated resources represented up to 24% of ODA back in 2009, compared to only just above 10% today.5 This general picture is confirmed by looking at the ‘Country Programmable Aid (CPA)’, an OECD indicator on the extent of country ownership in the deployment of development resources. As figure 3 shows, the Netherlands’ CPA as a percentage of total ODA is much lower than it was prior to 2010, confirming the downward trend of delegating resources to country-level. Moreover, the share of CPA in Dutch ODA today (17%) is significantly below that of other major donors, such as the United Kingdom (27%), Sweden (30%), Germany (37%) and France (50%).

Figure 3: Share of Country Programmable Aid in total Netherlands ODA

Source: Author, based on OECD database

The low share of delegated resources and CPA is not only problematic from a country ownership perspective; it could also, perhaps counterintuitively, lead to further aid fragmentation. Despite the aid effectiveness declarations of the 2000s, the fragmentation of the global aid architecture has only increased further. A recent World Bank study finds that the number of different bilateral entities providing ODA finance has ballooned from 145 to 411 over the past two decades and that the average size of each individual ODA activity has decreased by about one third. The OECD Peer Review notes that, for the Netherlands, the centrally-driven and thematic approach to programming actually worsens fragmentation. More use of thematic multi-country programmes run by Netherlands-based entities inevitably leads to a proliferation of smaller projects at country-level.

Support to the public sector has collapsed

A final indicator that is relevant when looking at the ‘how?’ of Dutch development cooperation is the share of ODA that is directed towards partner country governments. In 2012, the Netherlands decided to stop giving direct general budget support to governments, for reasons we will not go into here. This decision did not necessarily mean halting all support to governments – as there are many other forms of doing so beyond budget support – but in practice this is exactly what happened. By 2019, only 1.5% of ODA was spent through recipient country governments, compared to, for example, close to 20% up until 2009.6 This is unfortunate. The history of economic development, whether in Europe, the US, the East Asian Tigers, or successful African episodes of inclusive development, clearly shows the pivotal role of the state. The importance of the public sector is perhaps most obvious in social sectors like education or health care, but extends to virtually all policy areas. Building the capability of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs), smallholders and farmer cooperatives is important and can have great impact in the short-term; but without a capable and effective Ministry of Agriculture it is virtually impossible to stimulate sustainable agricultural development over the long-term. The same goes for other productive sectors. Industrial policy capability is vital to stimulate inclusive private sector development and job creation at scale. This area has been sadly neglected by the international development community in recent decades.

Sceptics of public sector support will point to corruption-related risks and the difficulty of attaining results in a context of widespread public mismanagement. These are valid concerns, but do not mean that we should ignore the public sector. In cases where general or sectoral budget support is simply not a feasible option, other avenues must be explored. There is ample evidence, for instance, on the potential of using a targeted approach for creating ‘pockets of effectiveness’, even in a context of general public sector ineffectiveness. With a more country-focused approach, development partners like the Netherlands could identify opportunities for supporting such pockets of effectiveness on the ground.

Conclusion

Over the past two decades, Dutch efforts on development cooperation have stagnated. A return to 0.7% would lead to a significant boost in available resources for Dutch development cooperation. That would not reduce the need, however, for the new government to make clear choices in terms of thematic and geographic focus areas, and stick to them. Development issues are complex, and to be effective requires deep knowledge of the themes and places one is working on. It should also be recognised, however, that tensions can emerge between a thematically and geographically-driven agenda. Too rigid an approach, whereby it is expected that in each partner country there is substantial engagement on each of the centrally-defined themes, should be avoided. There must be room for manoeuvre at country-level to pick the most relevant themes, leave out less relevant ones, or in certain cases even address new themes if there is a well-argued case to be made.

Finally, if the Netherlands is serious about improving the effectiveness of its development cooperation, it must put country ownership and local context at the heart of its engagement. This will require a substantial change in the way that programmes and budgets are designed and managed. In particular, the role of embassies in the partner countries will need to be strengthened, in line with the OECD recommendations. Increasing the share of delegated resources cannot be done from one year to the next; it must be a long-term effort. For, to enable embassies to spend more financial resources, they will also require more human resources, including development experts. This is key in order to internalise in-depth knowledge of the local (political) context and to foster the close relationships with local actors from government, academia, civil society and the private sector that are essential for true country ownership. It is only by having such a broad and deep in-country network that the perspectives of local actors can be taken on board in programming, right from the conceptual phase.

It is high time for a new government to reverse the trend of stagnated Dutch development cooperation efforts, and honour the commitment to spend 0,7% of GNI to promoting inclusive development for all. This is also in the interest of Dutch citizens. The COVID-19 pandemic has provided a stark reminder of global interdependencies. What happens on the other side of the world can have a severe impact on European countries. The most pressing global challenges, from tackling climate change to promoting global peace and security, cannot be successfully met without sustainable inclusive development in poorer countries.

Footnotes

- To name just a few: sustainable private sector development, youth employment, food security, nutrition, climate change mitigation and adaptation, water, gender, sexual and reproductive health and rights, mental health, security, strengthening the rule of law, civil society – the list could go on.

- West Africa & Sahel, Horn of Africa, Middle East & North Africa

- Based on Dutch government budget documents: HGIS Jaarverslag 2018 and HGIS Nota 2022

- Ministry of Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation

- Based on Dutch government budget documents: HGIS Jaarverslag for 2009 and 2020. Note that these are percentages of total ODA spending, including ODA-eligible expenses on the budget of other ministries, such as spending on first-year asylum seekers

- For 2019 see Dutch government budget documents: parliamentary questions and answers on HGIS Jaarverslag 2019. It shows that, in 2019, 43% was spent through multilateral organisations, 18% through civil society organisations, 6% through firms, while 22% is accounted for by spending that is not controlled by the Ministry of Development Cooperation, such as first-year asylum seekers and contributions to EU-led development cooperation.

For 2009 and before: See the evaluation of budget support: IOB (2012). Budget Support: Conditional Results, particularly Table 3.6 (page 76).