Western governments are increasingly reframing their rhetoric of engagement in fragile and conflict-affected areas around the development of a vibrant private sector. But how does this ‘new’ approach work in practice? Who are the ‘new’ beneficiaries and what kind of support is being provided? Looking at the Netherlands’ engagement in South Sudan and at the experiences of international and local entrepreneurs, this article illustrates some of the bottlenecks and challenges of this take on development, and identifies local entrepreneurship as a blind spot in the approach.

According to IMF estimates, none of the 20 countries with the highest projected growth rates for 2013-20171 are in the Western hemisphere. China is in ninth place and 10 of the 20 are in Africa. As such, it is becoming increasingly difficult for politicians in traditional donor countries to justify spending taxpayer’s money on aid abroad when domestic economic systems in the ‘developed’ world experience recession after recession.

Consequently, against the backdrop of extensive budget cuts in foreign aid, many Western governments are increasingly reframing their development rhetoric around the nexus of private sector development (PSD) in countries scoring the lowest on the Millennium Development Goals (MDG), namely fragile and conflict-affected states (FCS). This approach proactively seeks to involve international and local private-sector actors to compound trade and aid in places where high levels of unemployment, instability and a lack of inclusive economic growth are considered to be among the root causes of conflict and humanitarian disaster. The rhetoric combines the moral imperative to intervene in places where people suffer the most and to stimulate business interests at home and abroad.

In April 2013 the Dutch government approved a new development policy that is in many ways a prime example of how donors are integrating the emerging rhetoric about private-sector development in fragile states into their national policies. The new policy was formulated along the backdrop of a history of engagement in fragile countries like Afghanistan, South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and general pessimism about the role of conventional aid in a broader sense. Decades of development, with a focus on good governance and service delivery, have somehow missed out on working directly with the engine of economic development, the entrepreneur. Rather than waiting for ‘handouts’, entrepreneurs require ‘patient capital’, a long-term investment rather than ‘help’. Supporting entrepreneurs is more sustainable, because it creates less aid dependency by providing them with a more robust and stable source of income and knowledge transfer. This in turn will trickle down into society at large through employment and income generation. It will provide stability and contribute to the emerging middle-income strata in the long run, which is associated with improving government’s legitimacy and accountability as well.

Although, in practice, interventions have increasingly been designed according to this logic since the financial crisis in 2007-2008, it remains to be seen whether the ‘new’ paradigm of gainfully combining trade and aid will be any different than its predecessors. Lessons drawn from some of these interventions suggest that a ‘pull’ strategy may be much more conducive for supporting local entrepreneurs – and thereby also more beneficial for international firms – than the ‘push’ strategy on which aid is inherently predicated. In the volatile Republic of South Sudan, for example, local entrepreneurs struggle to find access to international support and investment from all major international organizations that are present. This is something to keep in mind when setting oneself with the task of ‘servicing the motor’ of a fragile economy.

Investment and job creation in fragile states

Much of the international discourse on private-sector development in fragile states references the World Bank’s 2011 World Development Report on Conflict, Security and Development. The report signalled that an alarming 17% of the world’s population lives in fragile and conflict-affected countries, none of which achieved a single MDG. In citizen surveys conducted for the report, unemployment was overwhelmingly the most important factor cited for increasing recruitment into rebel movements and for political instability. The report called for a paradigm shift in international assistance, stating that the problems these countries face cannot be fixed by short-term or partial solutions in the absence of institutions that provide people with security, justice and jobs. Positioning fragility, conflict and violence at the core of its development mandate, the report identified increasing attention to jobs and private sector development as one of the Bank’s six key themes for FCS reform.

But as donors started adopting this trend and realigning their priorities, there was concern among a number of Southern governments labelled as ‘fragile’ that this would again result in unrealistic expectations based on MDG-driven assumptions about their institutional capacities. As a result, in late 2011, 19 of these ‘fragile and conflict-affected’ state governments joined together to form the g7+ to provide “a fragile state perspective on fragility in order to work with donors to improve the effectiveness of their assistance” laid out in the ‘New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States’. The Chair of the g7+, Emilia Pires, pointed out that “private-sector growth and engagement is critical for meeting the peacebuilding and statebuilding goals and minimizing conflict.” Speaking at a Private Sector Investment and Job Creation meeting in Washington DC in April 2013, she noted that this was especially important for young people and reminded her listeners that the “priority is to do no harm and to maximize benefits” when designing investments.

What the world deserves from donors

The focus on promoting sustainable private-sector driven employment for stability, which is already mentioned as a core component of the third track of the UN’s 2009 three-track policy approach to post-conflict employment creation, has since been a recurring theme in the policy discourse on international fragile states. Through regulatory reform to increase the ‘ease of doing business’ in fragile and conflict-affected states, organizing trade missions for foreign companies and even through direct subsidies, donor governments try to encourage more companies to invest in FCS. Supported by the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and a number of other international financial institutions, more and more trade and investment conferences are being organized that emphasize the potential in these countries rather than the stereotypical characterization of warlords, famine and perpetual crisis as portrayed by the media. The message seems to be that, by working more with the ‘drivers of change’ from the private sector, we can organize aid in a smarter and more effective way and where it is needed most. Dutch policy reflects this (see box 1).

Box 1: Dutch trade and aid go hand-in-hand

The Netherlands is one of the traditional donor countries spending between 0.7 and 0.8% of its GDP on aid. In early 2013, however, Minister of Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation Lilianne Ploumen announced a new Dutch policy entitled, ‘What the world deserves: a new agenda for aid, trade and investment’. The policy has three overarching objectives: eradicating extreme poverty, promoting sustainable and inclusive growth, and helping Dutch businesses invest and become more successful abroad. The government prioritizes three types of bilateral relations – trade relations, transition relations and aid relations – with a smaller number of focus countries than before. Fragile and conflict-affected states no longer feature exclusively in the aid relations category, but also in the trade relations category. For example, Iraq and Nigeria, which ranked 11 and 16 respectively on the 2013 Failed States Index, are focus countries under the new policy. Despite budget cuts of €1 billion in all sectors except women’s rights and sexual and reproductive health rights (SRHR), the new policy contains a controversial proposal to establish an annual €250 million Dutch Good Growth Fund (DGGF). The DGGF has been set up to stimulate Dutch business interests abroad in a ‘sustainable and socially responsible way’, based on the OECD guidelines for multinational enterprises.

However, critics argue that the DGGF will essentially become nothing more than an export subsidy for Dutch companies. They claim that the expected developmental impact of these companies in recipient countries is questionable, although the details of the fund have not yet been clarified. By contrast, Dutch NGOs will receive substantially less support from 2016 onwards and are encouraged to reinvent their roles as ‘watchdogs’.[this means they are already or have been watchdogs and they have to reinvent that role. I suspect it means: ‘reinvent themselves to adopt the role of watchdogs’.

As is usually the case when politicians announce that something is ‘new and improved’, this shift towards working with and through the private sector in fragile and conflict-affected areas is part of a trend. It gradually gained ground during the previous government within the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs, within the headquarters of Dutch international NGOs in The Hague, and within many Dutch embassies in fragile and conflict-affected areas. As such, one can already see how the assumptions described above are expressed in existing interventions and how they correspond with local realities, as in the case of South Sudan, where over a dozen Dutch NGOs active and where the Dutch government is providing more than €200 million in official development aid (ODA) for the 2012-2015 period.

South Sudan: Booming for business?

In the case of the Netherlands, is most likely too early to say how these assumptions are expressed in concrete interventions and how they correspond with local realities in fragile and conflict-affected states. But behind the facade of the ‘new and improved’, the Dutch government, its embassies and Dutch INGOs that rely predominantly on government funding have already been trying this approach for some time in countries like South Sudan, Africa’s youngest state (see box 2).

Box 2: South Sudan, the world’s youngest state

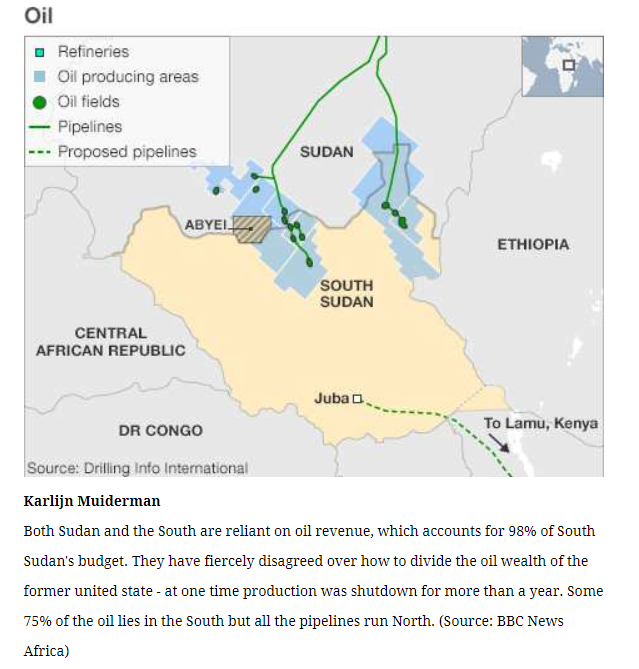

Between 1955 and 2005 Southern Sudan witnessed one of Africa’s longest civil wars, with an 11-year ceasefire between 1972 and 1983. The conflict claimed the lives an estimated two million people, most of whom were civilians, and displaced more than four million people from their homes. In July 2011, following a six-and-a-half year interim period as stipulated in the peace agreement from 2005, South Sudan gained its independence as Africa’s 54th state following a 98.8% popular consensus to separate. Two years after independence, South Sudan still struggles with its legacy of conflict, its lack of a consistent regulatory framework and its contentious relationship with its northern neighbour, Sudan. South Sudan’s only oil pipeline runs through Sudan and it is the only means for the South to export its most precious commodity, crude oil, which is responsible for 98% of its income. The 15-month oil shut down between early 2012 and 2013 over pipeline transit fee disagreements that precipitated a 56% drop in the infant economy’s GDP illustrates the volatility of its relationship with its northern neighbour.

Because the private sector is still in its early stages in South Sudan, profit margins are high for early investors. Chinese, Lebanese, Eritrean, Indian, South African and some American companies capitalize on this, but European investors remain hesitant. Nevertheless, business in South Sudan can be profitable but remains highly uncertain, as the recent events in mid-December 2013 have shown. The IMF’s April 2013 World Economic Outlook ranks South Sudan’s economy with the world’s second highest projected compound annual growth rate of almost 20% between 2013 and 2017. However, most of this growth is predicated on the young country’s abundant oil rents. The South has benefitted from this abundance of oil incomes since 2005, but nine years on, very little of the money has been re-invested into diversifying the private sector into local production and manufacturing. During the interim period between 2005 and 2011, the oil rents served the semi-autonomous South well in achieving internal stability, but in the longer run the oil industry provides very few jobs and has a tendency to become more of a curse than a blessing as it de-incentivizes exports, erodes the development of equitable state institutions, and fosters a political culture of rent-seeking behaviour. In short, diversification was the key to sustainable economic growth and employment, and the private sector was awarded the prophetic role to herald this trend, with the government limiting its role to creating an enabling environment and removing ‘obstacles to investment’.2

Unfortunately, however, South Sudan’s local private sector largely turned out to lack the resources, capacity and long-term vision to appropriate this role. The sector was heavily politicized and business success depended on connections with the ruling Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) elite in order to secure lucrative government contracts. Rather than limiting its role to creating an ‘enabling environment’, the government became the largest client and the local private sector revolved mainly around trade arbitrage and construction of roads, bridges and prefabricated ministries and hotels.

Unfortunately, however, South Sudan’s local private sector largely turned out to lack the resources, capacity and long-term vision to appropriate this role. The sector was heavily politicized and business success depended on connections with the ruling Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) elite in order to secure lucrative government contracts. Rather than limiting its role to creating an ‘enabling environment’, the government became the largest client and the local private sector revolved mainly around trade arbitrage and construction of roads, bridges and prefabricated ministries and hotels.

Meanwhile, many South Sudanese returnees from East Africa, Europe, North America and Australia started to become increasingly engaged in the local private sector. Although this group benefitted more from formal education abroad and often possessed promising entrepreneurial acumen, many of them lacked local knowledge and connections to secure the capital and protection to invest. As such, productive entrepreneurship in South Sudan depended on retaining legitimacy within local clientelist networks and simultaneously possessing the international business savvy and experience to attract foreign investment. Although this combination of features was uncommon, there were a number of local entrepreneurs who fulfilled both criteria and tried to establish themselves in commercial agricultural production, food production, river transport, fisheries and even small-scale industry, with varying success. Studies conducted among this group of entrepreneurs revealed a wide variety of thresholds and obstacles, but the most often cited challenge was that of finding suitable international partners to provide both expertise and long-term investment.

Civil unrest started in Juba on the night of 15 December 2013 and continues to destabilize the country to date. A split within the political leadership of the ruling party has left thousands dead, up to half a million people displaced and has seriously damaged the confidence that was beginning to show in the country’s nascent private sector. As a direct result, many local entrepreneurs have had to suspend or downsize their activities as investors bide their time, waiting for a political solution to stabilize the situation, which further complicates the international response.

In short, South Sudan’s private sector is subject to continuous uncertainty. Governed largely through informal institutional arrangements with the ruling elite, entrepreneurs need to understand how to carefully navigate this uncertainty. For international firms, finding a local partner able to do this is crucial, and not all local firms have productive potential, while many lack the ambition to progress past trade arbitrage. Notwithstanding, the minority of serious entrepreneurs who are both well connected locally and possess the business acumen to explore new productive niches struggle to find dedicated international investors. International firms, in turn, remain hesitant to invest in South Sudan as they struggle to separate the ‘wheat from the chaff’.

In short, South Sudan’s private sector is subject to continuous uncertainty. Governed largely through informal institutional arrangements with the ruling elite, entrepreneurs need to understand how to carefully navigate this uncertainty. For international firms, finding a local partner able to do this is crucial, and not all local firms have productive potential, while many lack the ambition to progress past trade arbitrage. Notwithstanding, the minority of serious entrepreneurs who are both well connected locally and possess the business acumen to explore new productive niches struggle to find dedicated international investors. International firms, in turn, remain hesitant to invest in South Sudan as they struggle to separate the ‘wheat from the chaff’.

A glance in the private sector development toolbox

The Netherlands’ efforts to promote local private-sector development in South Sudan are divided into a broad range of interventions. Some resources are pooled together with other donor funds and administered by organizations like the World Bank, for example throught its Private Sector Development Project (PSDP). This project aims to harmonize and simplify the regulatory framework in South Sudan to enable a conducive investment climate, working predominantly through South Sudanese ministries. Other resources are channelled through Dutch INGO funding such as the MFSII scheme or the 2012-2015 reconstruction tender focusing on youth unemployment, economic empowerment of vulnerable groups and value chain development. In practice, many of these projects also struggle to adapt their programmes to the local demands and needs of South Sudan’s survivalist economies and informal labour markets.

The Dutch embassy runs a number of facilities aimed at promoting local entrepreneurship and exchange with Dutch businesses. One of these is the Private Sector Investment Fund for fragile states (‘PSI plus’) which subsidizes foreign firms by providing up to 60% of the start-up capital to establish joint ventures with locally-registered companies in South Sudan. Local firms, however, cannot qualify for this subsidy as it is aimed primarily at the international partner company. A number of international firms have applied for this subsidy but so far with little success. Other instruments available to the embassies include the Netherlands Senior Experts programme (Netherlands Senior Experts programme (PUM), which matches retired international senior managers to local business cases to assist with re-organizations, takeovers or mergers. Within the South Sudanese private sector, most local firms would not qualify for this assistance as it is aimed mostly at large productive enterprises. So far, the PUM facility has been used once in South Sudan, and it yielded very positive results for the recipient local firm.

Finally, there are a number of initiatives that try to connect Dutch and international firms with local firms, most of which are also initiated and administered by the Dutch embassy in Juba. One example of this was the NABC trade mission October 2011, headed by former Minister for Development Cooperation, Agnes Van Ardenne, during which some 22 Dutch companies visited South Sudan and met with local entrepreneurs and government officials. The participating Dutch firms were mostly SMEs with portfolios in livestock services, dairy production, animal food production, high-grade construction equipment and horticulture. Most of them signed up for the mission to assess the local market potential for selling their services and products. Yet less than two years later, only one of the Dutch entrepreneurs remains active in South Sudan, while the other companies are yet to capitalize on the connections made and the available facilities.

Mismatch

One possible explanation for this could be that most of the participating Dutch companies came with the ambition of finding a local distributor for their high-grade (and relatively expensive) products and services, which is unrealistic in a market as underdeveloped and unspecialized as South Sudan’s. By contrast, the demand for basic and affordable yet durable products is very high, a relatively open niche that the low-grade Chinese and Indian products that have flooded the South Sudanese market have not managed to fill. Another possible explanation could be that many of the companies based their expectations largely on the embassy’s facilitative role and on Dutch government support to minimize the risks involved, rather than on finding a suitable and trustworthy local partner to negate these risks. In turn, the embassy was willing to assist and support these businesses, but at the end of the day they were required to take the initiative themselves. This has thus far not been the case, as the firms continue to be hesitant and reluctant to take the risks associated with South Sudan’s unpredictable environment.

Perhaps the most fitting example of direct matchmaking by the Dutch embassy is the matchmaking facility (MMF), available for local entrepreneurs seeking Dutch business partners for a joint venture. In theory, this initiative would be most compatible with the demands of local entrepreneurs, but in practice it is perhaps the least used and advertized instrument of all. Information about the MMF is scarce and few, if any, local entrepreneurs that could qualify are aware of its existence. In addition, the Dutch embassy lacks the resources and staff to proactively seek out suitable beneficiaries for the MMF, making its impact at most anecdotal.

Donors’ rhetoric about the key role of local entrepreneurs does not correspond with the level of the support they provide. The Netherlands is no exception in this regard. Local entrepreneurs struggle to find access to international support and investment by all major international organizations present in South Sudan, whose policy discourses embody the ambition of working with and through the local private sector to stimulate local production, employment and stability (see for example the business dialogue in box 3 below). Nevertheless, most of the facilities provided on the ground either target the most vulnerable groups, such as unemployed youth, or give priority to foreign business interests above local demands. As such, there appears to be a disconnect between what interventions aim to do and what they actually do.

Box 3: Key findings from a Dutch-South Sudanese business dialogue

In June 2013 the IS Academy on Human Security in Fragile States (for more information see box 4) hosted a one-day co-creation workshop about Dutch-South Sudanese private-sector linkages. It sparked an interesting discussion with a healthy realism regarding the current state of affairs. The attending policymakers, academics, NGO practitioners and private sector representatives from the Netherlands and from South Sudan highlighted many recommendations for the private-sector development paradigm, including the following:

- The point of departure for our engagement should be demand-driven business support. Start with what is there and not with what is not there. Facilities for joint ventures or matchmaking between local companies and international firms would be more effective if initiated locally, to start with a local demand/opportunity and seek the international partner accordingly.

- Flexibility is key: taking risks responsibly is a virtue in FCS. Chinese firms do not understand the market any more than we do when they arrive, but they are more pragmatic about risks.

- For Dutch companies, joint ventures or long-term investment do not have to be the first step. The first step is difficult when expectations are unrealistic and negative media coverage dictates the image of South Sudan. Instead, focus on firms that have already started an initial collaboration with a local distributor to see if there are any opportunities for expanding activities.

- Experience, legitimacy and connections of the local partner are the single most important deciding factors for business success in South Sudan. Embassies and NGOs can identify ‘ambassadors’ within the local private sector as connectors for Dutch businesses (example: local business owners with dual Dutch-South Sudanese nationality).

- What role can NGOs focus on?

- Employability training with focus on language (English);

- Matchmaking between local producers (groups) and larger SME firms in the capitals, as well as between local SMEs (not micro-enterprises) and Dutch social enterprises;

- Watchdog activities, specifically regarding conditions of employment and labour standards.

- Conflict-sensitivity is important, but an over-emphasis on inclusiveness is counter-productive. Concerns about inclusiveness and ‘trickle down’ of opportunities are often driven by Western donor-driven ideas about redistribution.

- International business linkages with the informal sector are unrealistic and problematic. To establish genuine joint ventures there needs to be a higher degree of formalization. This can be stimulated through government channels, but the reform should be more targeted to remove bottlenecks identified by the private sector rather than by the World Bank or by the government.

- There is a great demand for research, especially regarding:

- Labour markets: what skill-sets do local firms look for in their employees? How can these demands be made into a curriculum with the involvement of the local private sector?

- In places where there is not a historically vibrant entrepreneurial culture, returnees can be a prime source of entrepreneurial potential. What are the determining factors for the success or failure of an SME established by a returnee?

Push and pull factors in unpredictable markets

In the Netherlands, the political climate since the global financial crisis of 2007-2008 has been characterized by sentiments about a renaissance of the Dutch entrepreneurial spirit. This has subsequently been translated into national and international policy discourse in which transnational entrepreneurship and corporate social responsibility have become increasingly important. In the reviewed case of international development policy in fragile states, such presumptions then become embedded in the interventions and ‘pushed’ upon the local context. Instead, interventions should have taken local demands as a starting point. This phenomenon is as old as development cooperation itself and thus comes as no great surprise. However, when businesses become the recipients of aid, this mode of engagement is more problematic.

Generally speaking, in markets, consumers ‘pull’ products or services and suppliers ‘push’ them according to demand. Both strategies have their advantages and disadvantages and the circumstances that dictate the most appropriate strategy have been well documented. For example, when demand uncertainty for a certain product or service is very high, a push strategy makes very little sense. Push strategies are based on long-term forecasts, excessive inventories, and an inability to meet changing demand patterns, but require much less expenditure on advertizing than pull strategies. Alternatively, pull strategies are more suitable if demand patterns are volatile since they are principally demand-driven and require a much shorter lead time (time between initiation and execution of a process). They are, however, generally more difficult to implement. Applying this analogy to the support offered by donor governments, embassies and NGOs to local entrepreneurs, it becomes apparent that the interventions clearly adhere to a push strategy. While the highly uncertain nature of South Sudan’s private sector arguably requires more of a pull strategy for support.

Blind spots on the international radar

But can business logic be applied to international aid in fragile states? Obviously not: if a business applies a wrong push/pull strategy its shareholders will hold it accountable, whereas a donor’s ‘shareholders’ (Western taxpayers) do not expect any ‘return on investment’. Of course it is important that our governments, their embassies and the NGOs they financially support spend the ‘0.something%’ of our GDP responsibly. But at the end of the day international aid flows downward towards its recipients, whether these are Southern governments, famished children or promising social enterprises.

Donors like the Netherlands change their approaches every few years. Compared to five years ago there is indeed much more attention for working with and through the private sector, but how this new approach translates to practice remains largely unchanged – interventions are an extension of Dutch priorities in the current political climate. One of these priorities is to kickstart a renaissance of the Dutch entrepreneurial spirit. Herein lies an opportunity to change the way in which international donors have traditionally engaged in fragile and conflict-affected areas. In South Sudan, for example, where oil dependency and a highly-undiversified economy with enormously high unemployment rates are among the root causes of the enduring turmoil, efforts to support businesses to start producing and diversifying their activities could yield positive and long-term results. However, as noted earlier, most Dutch and international firms remain reluctant about investing in an environment as fragile and unpredictable as South Sudan. Experience suggests that the single most important factor in reducing this unpredictability and negating some of the risks involved for international firms to invest is a reliable local business partner. In turn, local entrepreneurs struggle to find international investors and appropriate support to help their businesses grow. Yet because donor interventions often take the foreign firm’s interests or short-term humanitarian objectives as a starting point, local entrepreneurs remain a blind spot on the international radar.

Brokerage to facilitate local-international business linkages could be a first step to address some of these mismatches between local realities and unrealistic expectations. Embassies have a potential role to play as a broker, a matchmaker between local SMEs and the Dutch private sector. But this brokerage role will continue to be limited if the services are only on a request basis and geared mainly toward donor-led interests rather than local demands.

The Dutch embassies’ matchmaking facility for local entrepreneurs to seek out potential partners sounds like an excellent idea, but the fact that the vast majority of serious local business owners are not at all aware that such facilities exist suggests that their impact is likely to be very limited. This tendency to de-prioritize local business opportunities and demands is common in many of the interventions described. Many participants at the foreign affairs workshop in The Hague last June 2013 felt that perhaps the instruments worked the ‘other way around’, by taking the interests and ambitions of Dutch firms as a starting point and considering local circumstances and the role of the local partner as secondary. A pull strategy – rather than the traditional push strategy used in aid – is therefore more likely to benefit both local entrepreneurs and international firms.

Box 4: The IS Academy on Human Security in Fragile States

The research conducted for this paper is part of the IS Academy on Human Security in Fragile States, which seeks to better understand the processes of socioeconomic recovery and the roles of formal and informal institutions in conditions of state fragility. It comprises several PhD trajectories and a number of shorter-term research projects geared towards catalyzing and cross-fertilizing exchange between policy, practitioners and academia in the field of socioeconomic recovery in fragile states. The IS Academy is a collaborative project between the WUR Special Chair for Humanitarian Aid and Reconstruction, the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ Department for Stabilization and Humanitarian Aid, five major Dutch NGOs and a number of other research institutes. For more information, please visit http://isacademyhsfs.org.

Footnotes

- International Monetary Fund. World Economic Outlook. October 2012. Projected compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) from 2013 through 2017. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2012/02/index.htm. In: Business Insider, The 20 Fastest Growing Economies In The World, 24 October

- As firmly stated in the donor-driven 2008-2012 South Sudan Growth Strategy and the 2011-2013 South Sudan Development Plan.