Now economists more and more accept the idea that inequality is rising in most parts of the world and harms sustainable economic growth, the obvious next step is to change the policies that cause it. Is redistribution enough or do we have to go further and challenge the notion that takes equality as a starting point for future economic growth?

In the run-up to the 2001 election, British Labour Prime Minister Tony Blair was asked if he thought it was acceptable that the gap between rich and poor was rising. His answer was: ‘If you end up going after those people who are the most wealthy in society, what you actually end up doing is in fact not even helping those at the bottom end’. 1 This could have been the answer of most politicians and policy makers during the optimistic period from the 1990s to 2008.

This optimism was based on a faith that competitive markets would generate a trickle-down effect as a result of economic growth. According to the economists of the neoclassical school, many of whom hold high positions in the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) and have advised on most governments’ economic policies, inequality in itself is not a threat as they believe that trickle-down will benefit the poor. The wealth created by competitive, open markets without government intervention will reach the poor through an increasing demand for labour.

The idea resulted in a development policy that saw economic growth as the way out of poverty, combined with the philosophy that all citizens are eligible to compete on equal terms. This ideal of equal opportunities, or equality of opportunities, 2 was translated into neoclassical economic policies that have quickly found fertile ground all over the world since the 1980s. It can be associated with open markets, deregulation and privatization with the aim of developing competitive market economies, and presumes a level playing field.

This economic view became mainstream in the 1980s and continued into the 1990s and beyond, and spurred a one-dimensional economic globalization agenda pursued by the World Bank, IMF, World Trade Organization (WTO) and most aid donors towards developing countries that relied on conditional support. Governments in developing countries had to open their markets to foreign competitors, liberalize labour markets, cut their expenditures on social security and education to lower their debt burden, and withdraw subsidies for farmers. Only a small number of countries with access to international capital markets, including India and China, opted out, although they continued to work closely with the multilateral institutions in their own ways.

The theory of mainstream economics on international trade and the reality of income inequality

The basic idea of competitive markets is that in open markets with few state interventions highly productive sectors benefit the most. Less-productive markets that need state interventions to survive disrupt the market mechanism at the expense of the productive sectors. In an open market the labour force will move away from sectors that are not performing to healthy sectors that can compete on an international level. The winning sectors become the cornerstone of economic growth and the economy will thrive because of their increasing competitiveness.

The shift of labour from one sector to another is assumed to go smoothly, perhaps with some disruptions for one generation; the focus is on the long-term benefit. However, to understand income inequalities within the context of globalization…

Inequality as a threat

Politicians and policy makers in 2012 no longer answer questions about inequality the way Tony Blair did in 2001. Inequality is now seen as a problem that can be tackled not only by the market but also by policy. High income inequality is recognized, also by economists of the World Bank and IMF, 3 as a major threat to future well-being and sustainable economic growth that cannot be solved by a trickle-down effect only (see the article ‘Stalling Growth and Development’ in this special report).

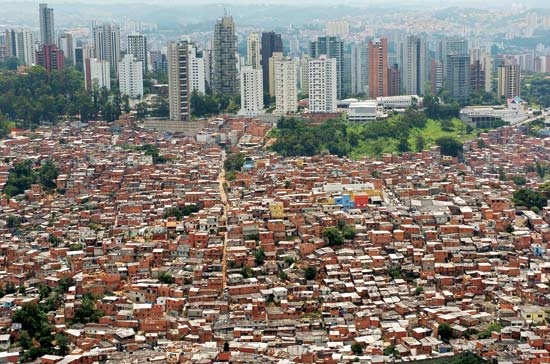

The neoclassical school assumes that in open markets the labour force will move away from sectors that are not performing to healthy sectors that can compete on an international level. This shift in labour from one sector to another is assumed to go smoothly. Box 1 shows that in reality it does not occur automatically, as spatial, social, and economic mobility is low and the skills required in the productive sectors are too high for many unskilled or low skilled workers. This happens in both developing and developed countries. The result is that the supposed increase in demand for labour thanks to economic growth is not reaching the very poor, at least not automatically through the market.

The idea that inequality matters is not entirely new. In the classic development literature, the links between growth and inequality have always been a major theme, as has been the debate about trickle-down. 4 The concept of pro-poor growth (economic growth that is good for the poor) 5 was prevalent in the 1990s and the early years of the new millennium, and the growth-distribution issue (using revenues from economic growth to finance redistribution policies) is as old as development practice. Both were, however, ignored by mainstream neoclassical economists who insisted that the growth-first model generated by competitive markets was good enough to reduce poverty. 6

The governments of a number of Latin American countries, like Venezuela, Brazil, Argentina and Bolivia, were among the first to openly criticize neoclassical economic policies and start experimenting with their own path to economic growth at the start of the new millennium. They do not believe in a one dimensional (orthodox) growth strategy to tackle poverty which ignores inequality. In China there has been increasing concern about the growth-first economic model since 1978 following three decades of egalitarianism. The Chinese authorities have recently reinforced a more egalitarian and inward-oriented development model. And what was known as the ‘Shining India’ model of the 1990s, which was based on the growth-first model, has now been recognized as having its political limitations as it excluded large parts of the population. 7

Shift in economics

It is safe to conclude that there is now a growing consensus that assessments of economic performance should not focus solely on overall income growth, but also take into account income distribution. 8 This is a significant shift within the spectrum of development economics in which redistribution policies, like those pursued for example by Brazil over the last decade (progressive taxation, cash transfers, minimum wages) to keep inequality under control, are now being taken seriously into account.

See, for example, the Economist’s 2012 special report on inequality, which seems to advocate moderate redistribution policies. 9 The authors conclude that it would be a serious mistake to separate analyses of growth and income distribution, but this should not lead to an unprecedented increase in policies to reduce inequality. Poorly designed efforts to reduce inequality could be counterproductive. They distinguish a number of win-win policies, including better-targeted subsidies, better access to education for the poor that improves equality of economic opportunity (see box 2), and active labour market measures that promote employment. Their claim is that, over longer horizons, reduced inequality and sustained growth may be “two sides of the same coin”.

There seems to be more space now for governments to intervene in the market, also among World Bank economists like Martin Ravallion, Shaohua Chen and Branko Milanovic. Some moderate redistribution policies to combat excessive income inequality may be permissible, but only to reduce the risk of it harming future economic growth. This does not, however, represent any fundamental change in the growth model of the neoclassical school.

A growing group of critical economists, like Joseph Stiglitz, Raghuram Rajan, Ha-Joon Chang, and Jean-Paul Fitoussi, are coming up with alternative solutions. According to them (and what is called heterodox economics; see box 3), the neoclassical agenda did not allow individual countries sufficient political space to seek their own paths to growth. Market mechanisms are not enough to determine wages and increase labour opportunities; interventions by governments and the bargaining power of employees are important, too. 10

According to these critics, the growth-redistribution strategy does not go far enough in tackling income inequality. They emphasize development models and economic policies that take local circumstances into account, favour local small businesses as the basis for employment and economic growth, and increase political space for interventions in the market. For them, tackling inequalities is about policies of inclusion not redistribution. The policies they embrace will change market structures in such a way that citizens feel part of the decisions that shape the market and their life. This implies redistribution of assets, new ways to access finance, and a production process that sees workers not only as human capital but provides decent working conditions and minimizes environmental damage.

Before returning to the current debate about the ‘inclusive economy’, however, first an overview of redistribution policies and what they have achieved in reducing income inequality in developing countries.

The base of equality: better skills and education for all

One of the most recognized policies to combat income inequality is to focus on education and to improve skills for the work force in the short term. For the neoclassical school this is not a threat but an opportunity to create competitive markets, and for their critics (heterodox school) investments in the education and skills of individuals are a proposition for inclusion. It is all about promoting equity in education. Investments in education make young people less dependent for their futures on social circumstances and the income level of their parents. Social mobility will rise and this should boost GDP per capita by enhancing productivity. The outcome is a more equitable distribution of labour income. The Asian tigers (South Korea, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Singapore) in particular, and China to a lesser extent, combined export-led industrialization with major investments in education for all.

What can be done to transform unskilled and low-skilled workers into better skilled workers with opportunities in competitive markets? A short-term solution is to give workers the time and training to prepare them for work in sectors that require higher skills. However, poor countries do not have the capacity and money to invest in such programmes to help out workers that suffer from free trade in the short term. For developing countries this is further complicated as the poor are stuck in the informal economy, which prevents them from developing skills and improving their incomes.

The economics of redistribution

Redistribution policies aim to redistribute the wealth generated through economic growth from those who have benefited from it to those who have not. They include progressive taxation, cash transfers to the poor and other social transfers like pension funds or social insurance programmes. Some of the innovative policies introduced recently by a number of countries in Central Europe and Latin America to maintain the incomes of the unemployed try to challenge inequality. Among these are conditional transfer and employment activation programmes. 11

In Latin America particularly a number of successful conditional cash transfer policies have been pursued in the last decade. According the World Bank these transfers have become the star social programmes in the region, achieving good results in fighting inequality, because “they aim to intervene in the causes of poverty and not just in the symptoms”. 12 They were built around a number of basic principles: expanding health care, education and nutritional services through conditional mechanisms, integrating cash transfer programmes with the rest of the social protection system, and reducing poverty through the transfer of cash to selected families. Examples are the Bolsa Familia in Brazil and Oportunidades (formarly PROGRESA) in Mexico, that give the poor a cash flow from the state under certain conditions, like their children attending school.

Most of the programmes have incorporated millions of people into welfare systems that had historically excluded them because they were working in the informal economy or in parts of the formal economy that were fell outside the system. Impact evaluations of conditional cash transfers in Latin America have shown promising results. Large-scale programmes like the Bolsa Familia and Oportunidades and, to a lesser extent, smaller ones like Programa de Asignación Familiar in Honduras and Red de Protección Social in Nicaragua, have had positive results in directly reducing inequality (short-term impact on income inequality). 13There is also evidence of positive impacts on education and health outcomes (long-term impact on income inequality). Furthermore, conditional cash transfers have prevented workers from becoming increasingly dependent on the state for their income.

Orthodox versus heterodox economics

Orthodox economics are mainstream economics with theories that are part of the neoclassical economics tradition. The market is the best place to determine wages, prices, employment and economic growth. Protagonists of orthodox economics (e.g. Friedrich Hayek, Paul Samuelson, Milton Friedman, Robert Lucas) are sceptical of the role of governments and do not focus on economic concerns like sustainability, pollution or inequality. Political interventions are not needed as they will disturb market mechanisms. Within the mainstream, distinctions can be made between the Saltwater school (associated with Berkeley, Harvard, MIT, Pennsylvania, Princeton and Yale), Keynesian ideas that government has an important ‘discretionary’ role to play in actively stabilizing the economy over the business cycle, and the more laissez-faire ideas of the Freshwater school (represented by the Chicago school of economics, Carnegie Mellon University, the University of Rochester, and the University of Minnesota).

A common definition of heterodox economics is that it ‘seeks to embed social and historical factors into analysis, as well as evaluate the way in which the behaviour of both individuals and societies alters the development of market equilibriums.’ It looks for alternatives to mainstream economics. The basic schools of heterodox economics were the established paradigms of Austrian, Institutional-evolutionary, Post-Keynesian, Socialist, and Sraffian economics. Famous protagonists of the heterodox school include John Davis, Frederic Lee, T. Lawson, Nancy Folbre, Marianne Ferber, Julie Nelson, and Irene van Steveren. Nowadays there is much more cross-fertilization of ideas, creating a new generation of scholarship.

How can redistribution be financed?

Countries that spend more on social transfers (social assistance benefits, pension schemes, social insurance programmes, and cash transfers) tend to have lower income inequality. Data also shows that most high-inequality countries lack the money to fund social programmes. 14One explanation is that in developing countries, social insurance programmes (such as pensions and unemployment insurance) are too expensive for the poor and tend to exclude workers in the informal economy, who comprise a disproportionate share of the poor.

Some African countries have a long tradition of social transfers. Mauritius and Namibia have longstanding universal basic pension schemes. Even less-developed Mozambique has implemented the Programa de Subsidio de Alimentos, a social transfer programme for people unable to work, which has more than 100,000 beneficiaries. 15 However, this is more the exception than the rule on the continent. Social transfers in Sub-Saharan Africa are regularly criticized as there is a widespread perception that they divert resources from investment in infrastructure and much-needed spending on social services like public (free) provision of primary and secondary education and primary health care.

Many developing countries are also struggling to set up equitable and efficient tax policies. Taxes are key to financing social policies and cash transfers, and progressive taxation can directly affect inequality (see box 4). Middle-income countries, but low-income countries even more so, therefore face a dilemma. Opening up the economy may provide opportunities for export-led growth and a rapid rise in GDP, but may also exacerbate internal inequalities. Countries with effective systems of government can cope with this, as they encourage export-led growth through investment in physical and social infrastructure and at the same time invest in social policies and internal redistribution schemes (social policies, conditional cash transfers, labour market interventions, a progressive tax system) to reduce the negative effects of their growth strategy. But most developing countries, especially those with weak institutions, are unable to make such an effort. For them inequality continues to hamper economic growth.

Taxation

The mobilization of domestic resources through tax reform was considered a pillar of the 2002 Monterrey Consensus on Financing for Development and its follow-up declaration in Doha in 2008. Despite all the efforts, developing countries still struggle to establish domestic taxes like income and consumption taxes (VAT). There are problems with underpayment caused by tax avoidance by the rich and high levels of informality among the poor. Also trade liberalisation diminished one of developing countries’ most important tax revenues as import and export taxes were rolled back significantly. Hence, the tax system as a whole became more regressive because consumption taxes have to be paid at the same rate by the whole population. Meanwhile property taxes and taxes on corporate income, profits and capital gains have on average fallen in most developing countries, largely because of increased global competition and tax avoidance through tax havens (See also The Broker’s article ‘Money on the move’).

See for example Richard M. Bird and Eric M. Zolt, Redistribution via Taxation, The limited role of the Personal Income Tax in Developing countries, International Tax Program, Institute for International Business, University of Toronto, Paper 0508

The inclusive economy

Most redistribution schemes remain little more than a trade-off between reducing inequality and promoting economic growth. Governments use income distribution schemes to attenuate negative impacts on the poor, but this cannot take away the profound causes of inequality, which are fuelled by the neoclassical one-size-fits-all approach to economic globalization, 16as has been shown above and in box 3. What is now known as the ‘inclusive growth’ approach is a response to the shortcomings of such redistribution policies.

The discussion on inclusive growth has been driven by emerging countries. The term inclusive economics was coined by in 2001 Indian economist Narendar Pani, editor of the Bangalore Economics Times, who used the term to refer to a ‘Ghandian method’ of selecting economic tools for policy making. 17 This does not mean that the debate about inclusion is only a Southern one, but it is the emerging countries in Latin America (e.g. Brazil), Asia (e.g. India and China), and Africa (e.g. South Africa) that struggle the most with high growth rates and growing inequalities. As a result, inclusive growth has internationally been promoted by the Asian and African Development Banks.

The 2008 financial crisis, which was followed by the worst economic crisis in decades, made the inclusive economy more and more of an issue of both emerging and developed countries. But, in developed countries, there was already a turn towards more inclusiveness before 2008. Take for example the Commission on Growth and Development, an independent body chaired by Michael Spence that brought together 22 policy makers, academics and business leaders to examine various aspects of economic growth and development. 18 It was set up in 2006 and added the term ‘inclusive development’ to the title of its flagship publication. UNDP renamed its International Policy Centre (IPC) ‘IPC-IG’ (IG stands for inclusive growth). 19

There are, however, different definitions of inclusiveness. 20 One, for example, emphasizing the extent to which the poor benefit from growth, is more or less a continuation of the pro-poor growth debate. Another definition, which seems to be embraced by the Growth Commission and the World Bank, 21 focuses on participation in generating economic growth (growth is based on the inputs of those, including the poor, who contribute to it). This concept of inclusion allows the excluded to be agents whose participation is essential in the design of the development process, rather than simply the welfare targets of development programmes.

However, heterodox economists like Charles Wheelan, Burton Malkiel, Diana Coyle, Jonathan Schlefer, and others argue that such notions of inclusiveness remain embedded in the neoclassical growth theory. 22 They call for social equity and environmental sustainability issues to be factored more accurately into economic accounting and analysis beforehand, rather than as an afterthought. For them, inclusiveness is less about creating growth and more about reaching a higher stage of wellbeing. Economic development means more than eradicating absolute poverty or creating employment. It is about looking at decent wages, good working conditions and bargaining power for employees, and fine-tuning economic strategies to suit local conditions. 23

Economic policies based on equality

Policies would look different if politicians embraced the inclusive economy. They would likely emphasise social spending, as well as a productive approach that for example emphasizes changes in market structures to combat discrimination in labour markets and unequal access to finance. Policies would take into account the spill-over effects of the production processes. For instance, people in marginalized positions cannot defend themselves against environmental damage and pollution, like oil spills or mining activities that pollute drinking water in rural areas and threaten small farmers.

Such a development approach would include greater accountability, more (international) responsibilities, and the engagement of the private sector. Politicians would not think about growth-first or the redistribution of wealth, but about the extent to which people feel they take part in the decisions that shape their life. It is likely that many people want to be more than ‘beneficiaries’ of growth, and want to be in a position to use their creativity to shape growth patterns themselves and be part of the decision-making processes that promote these patterns. 24

Furthermore, policies for inclusive growth need to focus on the conditions under which small entrepreneurs – including in the informal and rural sectors – generate their livelihoods, on the redistribution of assets and other opportunities to participate in growth processes, and on the conditions of employment, which is the single-most important source of livelihood for poor people. 25 With such attempts at economic policies that move beyond the growth-redistribution dichotomy, the agenda to combat income inequality will be enhanced and social equity and wellbeing will be factored more accurately into economic accounting and analysis.

Co-readers

Arjan de Haan, Program Leader, for ‘Inclusive Growth’ at the International Development Research Centre, Canada.

Nicky Pouw, development economist and assistant professor in the International Development Studies programme at the University of Amsterdam (UvA), the Netherlands.

Footnotes

- Wade, R.H. Income Inequality: Should We Worry About Global Trends?, The European Journal of Development Research, Special debate section: The Politics of Poverty and Inequality, September 2011, Vol. 23, No. 4.

- To read more about equality of opportunity see the website of Stanford University.

- Berg, A.G. and Ostry, J.D., Equality and Efficiency, Finance & Development, September 2011, Vol. 48, No. 3.

- e.g., Adelman and Morris 1973, Ahluwalia 1974, Kuznets 1955, Acemoglu and Robinson 2002 on the political economy of a Kuznets curve, Pernia 2003.

- The absolute definition of pro-poor growth considers only the incomes of poor people. How ‘pro-poor’ growth is should be judged by how fast on average the incomes of the poor are rising. The relative definition of pro-poor growth looks at poverty and growth from another angle. It compares changes in the incomes of the poor with changes in the incomes of people who are not poor. Growth is ‘pro-poor’ if the incomes of poor people grow faster than those of the population as a whole. The absolute definition of pro-poor growth enjoyed preference throughout the 1990s and from the start of the new millennium as the basis of efforts to fulfil the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals. One of the concerns that was raised – particularly against a relative definition of pro-poor growth – was that policies that follow might neglect improvements in the average and for the entire population distribution.For more information read for example: J. Humberto Lopez’ (World Bank) paper or the DFID (2004) briefing or the Briefing Paper(2008) of the Overseas Develoopment Institute.

- de Haan, A. and Thorat, S. , Inclusive growth: more than safety nets?, SIG working paper 2012/4, December 2012, International Development Research Centre, Ottawa.

- Ibid.

- OECD, Economic Policy Reforms 2012, Going for Growth , Part II, Chapter 5, Reducing income inequality while boosting economic growth: can it be done?

- The Economist special report of 13 October 2012 makes three arguments. First, that a major driver of today’s income distribution is government policy. Second, much of today’s inequality is inefficient, particularly in the most unequal countries. It reflects market and government failures that also reduce growth. Third, it promotes a reform agenda that should reduce income disparities ‘whatever your attitude towards fairness’ without higher taxes and more handouts. What it calls ’true progressivism’ means investing in the young generation.

- Harvard Business Review Blog Network, How Economists Got Income Inequality Wrong, by Jonathan Schlefer, 9 November 2012.

- International Poverty Centre, Cash Transfers: Lessons from Latin America and Africa, Poverty in Focus, Number 15, August 2008.

- World Bank, Conditional Cash Transfers: Reducing Present and Future Poverty, 2009.

- International Poverty Centre, Cash Transfers: Lessons from Latin America and Africa, Poverty in Focus, Number 15, August 2008.

- Prasad, N., Policies for redistribution: The use of taxes and social transfers, International Institute for Labour Studies, Discussion Paper l94, 2008

- International Poverty Centre, Cash Transfers: Lessons from Latin America and Africa, Poverty in Focus, Number 15, August 2008.

- Wade, R.H., Income Inequality: Should We Worry About Global Trends?, The European Journal of Development Research, Special debate section: The Politics of Poverty and Inequality, September 2011, Vol. 23, No. 4.

- Pani, N. (2001) Inclusive Economics. Ghandian Method and Contemporary Policy, Sage Publications.

- The Commission on Growth and Development (informally known as the Growth Commission) set out to take stock of the state of theoretical and empirical knowledge on economic growth with a view to drawing implications for policy for the current and next generation of policymakers. The Commission’s work culminated in two publications – The Growth Report: Strategies for Sustained growth and Inclusive Development (May 2008) – and a Special Report on Post Crisis Growth in Developing Countries (October 2009). Five thematic volumes and nearly 70 working papers were also published by the Commission. The Growth Commission’s work was sponsored by the governments of Australia, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and Sweden, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, and the World Bank Group. The Commission’s activities formally ended in June 2010.

- The IPC-IG international workshop in December 2010 focused on the BICs.

- See: Klasen, S (2010) “Measuring and Monitoring Inclusive Growth: Multiple Definitions, Open Questions, and Some Constructive Proposals.” June 2010 Working Paper Series No. 12. And: de Haan, A. and S. Thorat, Inclusive growth: more than safety nets?, SIG working paper 2012/4, December 2012, International Development Research Centre, Ottawa.

- See the World Bank resources article ‘What is inclusive growth?’ of 10 February 2009.

- See for example: McGregor, A. (2004) ‘Researching Wellbeing. Communicating between the Needs of Policymakers and the Needs of People’, Global Social Policy, 3: 337-358; Ostrom, E. (2010) ‘Analyzing collective action’, Agricultural Economics, International Association of Agricultural Economists, 41(s1): 155-166; Pouw, N.R.M. (2012) ‘The Inclusive Economy Framework’, GID Working Paper, University of Amsterdam; Schlefer, J. (2012)The Assumptions Economists Make, Harvard University Press; Stiglitz, J., A.K. Sen and J.P. Fitoussi (2008) ‘The Measurement of Economic Performance and Societal Progress’, Paris: International Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Societal Progress; Wheelan, C. and B. Malkiel (2003) Naked Economics. Undressing the Dismal Science, New York: Norton Company.

- From Nicky Pouw: Heterodox economists envision something differently when talking about a more comprehensive or inclusive approach to economics; they challenge the basic premises of the discipline (e.g. Wheelan and Malkiel 2003; Coyle 2008; Schlefer 2012). Heterodox economists argue that social equity and environmental sustainability issues need to be factored in more accurately in economic accounting and analysis beforehand, instead of as an afterthought. They propose alternative economic concepts, questions and axioms from different angles. First, from the contention that an increasing share of economic production and trade consists of ‘intangibles’; services, using both tangible and intangible goods and high levels of human capital (e.g. financial services, health services), which are notoriously difficult to measure (Stiglitz et al. 2008). For this reason the authors of the ‘Sarkozy report’, Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi, suggest a more encompassing indicator than the conventional GDP to measure economic performance and societal progress. Second, from the notion that welfare inadequately captures quality of life, by focussing exclusively on material welfare and overlooking social relationships and coginitive/subjective dimensions. Wellbeing, instead of welfare, should therefore feature at the centre of our economic development concerns. Cultural values and moral influence economic behaviour and explain the complexity of economic decision making at the microeconomic level (e.g. McGregor 2004; Coyle 2008). Third, out of a concern for the loss of natural resources in the current economic growth process. The irreparable loss of environmental assets undermines future growth and wellbeing. This fuels the argument for low/no growth whilst adhering to calculated environmental boundaries and making environmental investments (e.g. Ostrom 2010; Jackson 2011; Coyle 2012; and many environmental economists and non-economists before them). Fourth, and finally, from an integrated perspective on the economy that understands the economy from the multiple interconnections between the paid and unpaid economy modelled by the Inclusive Economy Framework (Pouw 2012). Many heterodox economists will gather at the upcoming OECD conference on Economics for a Better World in Paris, 3-5 July 2013.

- de Haan, A. and Thorat, S., Inclusive growth: more than safety nets?, SIG working paper 2012/4, December 2012, International Development Research Centre, Ottawa.

- Ibid.