In the debate about the decolonisation of the aid industry, it is often argued that true decolonisation will be realised if the international aid system abolishes itself. Only last month, in a first webinar in a series on ‘The Decolonization of aid’ however, historian Prof. Bertrand Thaite warned that, while decolonisation is of crucial importance, we have to be careful not to throw away the baby with the bath water. In the second session in this series, again organised by Kuno, Partos and the International Institute for Social Studies (ISS), we explore this conundrum further. Focusing in particular on development cooperation, we ask ourselves how this proverbial ‘baby’ – a baby that might be named ‘global solidarity’ – can be saved and nurtured into the new being we envision? If we dismiss the option of abolishing development aid altogether, what other paths are open to meaningfully transform the development sector? Building on the insights and conversations of the first session in which speakers Dr. Arua Oko Omaka and Prof. Bertrand Thaite enlightened participants with a historical perspective, for this second session speakers Tulika Srivastava and Lydia Zigomo challenged the audience to take a critical look at present-day practices of the development sector.

Unpacking the colonial system

Once more hosted by Kiza Magendane, writer and knowledge broker at The Broker, and professor Dorothea Hilhorst, professor of Humanitarian studies at ISS, the second session, taking the perspective of development cooperation, was marked by a constructive spirit. Yet, as both speakers in this session agreed, starting with a thorough deconstruction of the current system will be a necessary first step. This deconstruction already commenced during the previous webinar, when the interlinked nature of the colonial and humanitarian project was critically assessed. The opening arguments of Tulika Srivastava, the first speaker of this session, seamlessly followed this historical perspective. According to Srivastava, human rights lawyer and director of Women’s Fund Asia – a feminist regional women’s fund that supports women-, girls-, trans-, and intersex- people led interventions to enhance and strengthen access to their human rights – only by understanding the complex nature of colonialism, past and present, can we begin to tackle its ongoing impact today. Unpacking the ‘black box’ of colonialism, Srivastava argued, will reveal how much colonial experiences vary. Not only between the Global South and the Global North, but also between different countries and communities within the Global South. These colonial experiences affect the way in which current development efforts and the colonial elements therein are perceived and experienced. Without understanding such differences, transforming the development sector will be ineffective, as Lydia Zigomo, the second speaker of the webinar agreed. There is no one-size-fits all solution to the decolonisation of international aid. Rather, it is an ongoing process of transformation that must be driven by the specific needs and realities of local communities.

Zigomo, the newly appointed Global Programmes Director of Oxfam International, recently published a blog in which she shared how she experienced the ‘white saviour’ mentality that still permeates through many aspects of the development sector. By showing, in addition, how Oxfam is currently working to transform its agenda and operations, Zigomo does not linger on her often disheartening experiences, but ends her essay with a constructive call for action. Reiterating and further specifying Srivastava’s line of thought, Zigomo argued that the first step towards a decolonial development agenda is the recognition that development cooperation is not a neutral, isolated phenomenon. On the contrary; development cooperation operates within, and at the same time perpetuates, a much broader (colonial) system. Unpacking development cooperation in this fashion it becomes clear that it is not development cooperation itself but the system in which it is embedded that needs to be decolonised.

In essence, the nature of the system in which development cooperation operates is determined by power and control. In the colonial era, this system was dominated by and served the interests of a limited number of European power holders at the expense of a vast majority of indigenous people. Today, even though European colonialism is no longer a judicial reality in contemporary Africa, the West continues to perpetuate colonialist practices and indigenous people are still treated as second class citizens. While it remains necessary, therefore, to critically discuss the power position of the global North, Zigomo warns that we should not lose sight of colonialism by other external actors as well as ‘home-grown’ colonialism. New players, including China and multilateral organisations, and a small self-enriching indigenous elite are keeping the colonial system very much alive. “While we may have overturned white rule to black rule in the African struggles for independence, this black rule is really ‘elite rule’,” Zigomo noted. “And one can question how much this system really differs from white rule in the past.” What both Zigomo’s and Srivastava’s arguments boil down to is that the multiple layers and players of contemporary colonialism need to be unpacked. By failing to do so, we will end up with ‘a changing of the guard’; that is, the continuation and recreation of the current ‘colonial’ system of power and control with different power holders on the top, at the continued expense of the overall majority of people.

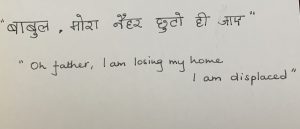

Throughout the webinar series on the decolonisation of international aid, the invited speakers are asked to select an image that illustrates their analysis on the (de)colonisation of aid.

Tulika Srivastava, human rights lawyer and director of Women’s Fund Asia, brought an image of a handwritten line from well-loved poem. The poem was originally written in 1857 by Wajid Ali Shah, the Nawab of Awadh – an Indian princely state (now part of Uttar Pradesh) – at the time of his arrest and exile from Lucknow by the British after the first war of Independence in the same year. It reads: “Oh father, I am losing my home. I am displaced from myself.” For Srivastava, the sentiment in this line represents the colonialism in development efforts. Those who are given aid have been ‘displaced’ from their own experience and reality, and have no or limited influence on development interventions. Activists of the global South are being denied agency in ownership of the development agenda. It is the North that is determining the agenda; the South continues to be displaced.

Poem by Tulika Srivastava

Lydia Zigomo, recently appointed Global Programmes Director of Oxfam International, held up a Kenyan ceramic bowl. For her, this bowl stands for Oxfam’s ongoing transformative journey. Like so many other development NGOs, Oxfam approached the countries it was working in as a ‘begging bowl’: The approach and language used were marked by a relationship of donor and recipient. Once Oxfam started its journey of decolonisation, the ceramic bowl could no longer represent the relationship between Oxfam and its Southern partners. Now that Oxfam and other organisations are increasingly taking a human rights approach to their practices, a beautifully coloured glass vase has replaced the bowl. The people in the global South are not mere recipients or beggars holding up a bowl. They are people full of ideas, creativity, and agency, able to co-create solutions to their own challenges.

‘Begging bowl’ presented by Lydia Zigomo

Part of the package: patriarchy and women’s inclusion

In an attempt to deconstruct colonialism and build a decolonial agenda for development cooperation, both speakers highlighted the importance of a critical reflection on dominant gender norms and practices. Colonialism, Srivastava noted, rides on and benefits from patriarchy. Similarly, by explaining the importance of intersectionality as a key concept in our efforts to decolonise development aid, Zigomo also demonstrated how colonialism and patriarchy are historically interlinked. The African feminist movement has gained an understanding of this connection: The colonial system has negatively affected black women disproportionally, providing a legal and political framework that allowed for the disinheriting and disenfranchisement of women, more so than men. Unpacking this element of colonialism makes clear that, within the current system, various levels of power and disempowerment still exist. Meaningful decolonisation and transformation thus also implies challenging persistent cultural practices in the Global South that undermine the position of women – and, as goes without saying, other disadvantaged groups – in society. Srivastava added that this fight against gendered injustice and for gender equality, as part and parcel of the decolonising project, should not be limited to a particular region or to the global South. Rather, she stressed, it is a universal struggle that testifies to the connected fate of women everywhere. In her response to the reflection of both speakers, Professor Hilhorst firmly agreed, noting that the persistent patriarchal power dynamics also affect the way in which this road towards transformation and the development sector itself are organised: Organisations that are facing most barriers to get a seat at the table are the feminist organisations.

“It is not your money. This money is a public good for a social purpose. We are holding money in trust for social justice and transformation.” ~ Tulika Srivastava

Painful but promising steps in the journey towards transformation

What are the implications of deconstructing colonialism and the world order in which development cooperation is embedded? According to Zigomo, as is the case for every process of de- and re-construction, some tough decisions must be made and some painful losses are inevitable. For International NGOs (INGOs) in the Global North, this process demands a ‘stepping back’. Both Zigomo and Srivastava stressed that a true transformative approach to decolonisation requires from INGOs in the global North that they scale down and become smaller, allowing for their Southern national and regional colleagues to take the lead. “We cannot continue to remain such massive organisations and at the same time seriously claim that we are making space for the national, Southern partners,” Zigomo noted. But the process does not end with making space at the decision-making table. Rather, Srivastava added, we must determine how power can effectively be shifted to the South. To answer that question, again, the North must take a step back. “We need to hear from the leaders of the Global South, without shifting the burden on them,” Srivastava argued. “What is it that they think is needed, what path do they see as the way forward to make decolonisation happen?”

From her experience as a grantmaker in the global South, Srivastava has learned that radically changing existing funding mechanisms is a promising pathway to realise transformational change. She observed that in the current system, project proposals are often formulated and imposed by those organisations that are holding the purse-strings. They are not based on the views, needs and realities of the people in the South, let alone formulated by these people. A truly transformative approach should let local communities, and especially local women, take the lead in their own language and voice. Additionally, Srivastava pointed to the importance of flexible funding mechanisms that change with and support, rather than add an extra burden to, organisations that are already facing great challenges at every turn.

The importance of such flexible funding schemes has become particularly clear during the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to lock downs and other measures related to fighting the pandemic, organisations’ needs changed dramatically and at the same time, they were barely surviving. A key lesson that can be taken from Srivastava’s experiences during the pandemic is that funds should be organised in such a way that they are granted to organisations on the basis of trust and solidarity, helping them to realise their goals, even if these goals are radically altered to match the changing reality on the ground. It is in this spirit that Women’s Fund Asia extends its grants to partners: given them breathing space and following their lead rather than imposing stringent criteria and sticking to pre-designed plans. The partners knew they could count on the Women’s Asia Fund, and that the organisation had their backs. In other words: they experienced a transformation of the relationship between grant-giver and recipient. Even though money was exchanged, they formed a true partnership.

Finally, a transformational approach to decolonisation also means that Northern organisations and grant organisations should realise that they are not the owners of the resources that they hold. They are entrusted to keep the money for the people in the South safe. “It is not your money. This money is a public good for a social purpose,” Srivastava passionately stated. “We are holding money in trust for social justice, we are holding it in trust for transformation. Without this realisation sinking in and becoming part of the development sector’s DNA, fundamental changes of the system cannot be realised.” It is a message that resonates with Zigomo. “When we start saying ‘my money’ and when we start appropriating, then our own agenda also comes around the corner,” she added. In other words, decolonisation means that organisations should do more than embracing beautiful words. It means translating these words into action, by making tough decisions and put Southern organisations at the centre of decision making and implementation.

COVID-19 as an opportunity for solidarity and decolonisation

As already became clear in the plea for flexible funding, COVID-19 – in addition to its devastating impact – has highlighted some promising pathways towards decolonisation. Importantly, the pandemic has demonstrated the necessity to reshape international cooperation and humanitarian aid structures. As Zigomo pointed out, for example, first responders during the various waves were almost invariably local people and organisations. “This is something we should celebrate and hold dear,” she argued. The COVID-19 response has shown that the ‘South in the lead’ is not just a lofty slogan but something that can, and has been, realised. “We should take this insight and use it as an impetus to make lasting changes to the way we have organised our aid and development systems.” ‘Shift the power’ and ‘decolonise aid’ are possible.

“Tackling institutional racism and decolonising aid is a life-long journey. There will always be another hill to climb when you think you have reached the summit.” ~ Lydia Zigomo

Despite the growing awareness about the interconnected nature of the world as a result of the pandemic, vaccine nationalism and increasing global inequality illustrate the vulnerable nature or even lack of global solidarity. At the same time, however, surprising initiatives across the globe may inspire hope that solidarity is, in fact, still very much alive. Yet, even though such solidarity always has a basis in good intentions, Zigomo warned, often ‘a guilty conscience’ and ‘helping the poor Africans’ – in other words, colonial sentiments – still inform solidarity in the Global North. What then, does solidarity mean in a transformed and decolonised world? For Srivastava, ‘standing in solidarity’ should always – but especially now in the response to the COVID-19 pandemic – mean that the international development sector takes a moment and lets itself be led. “This is not the moment to come up with new frameworks, programme designs. We should listen to and follow the lead of local organisations and communities.”

Solidarity in a decolonised, transformed world means supporting from a position of trust, humility, respect and equality. For the development sector the question remains: Are we willing to continue down this difficult path of transformation, pay the prices that are due, and in the end stand in true solidarity with those we want and claim to support? If we are, this commitment is one that must be made for the long term. To quote from Zigomo’s blog: “Tackling institutional racism and decolonising aid is […] a life-long journey. There will always be another hill to climb when you think you have reached the summit. It requires courageous leadership to make strategic, difficult choices and it requires persistence to deploy the right resources to support that journey.” Additionally, it is a journey that cannot be completed by a handful of organisations or people; it demands involvement and patience of all actors involved. And finally, it is a journey that must go far beyond the development sector. The path must take us to visit and transform the broader power structures in which all our behaviours, relations and assumptions are embedded. It is still a long road ahead, but it is a road that, if we take it, will yield the greatest reward.