As the influx of migrants to Europe unfolds as the biggest humanitarian and political crisis of 2015, European policy-makers are being challenged to come up with unified responses. Currently, they mainly focus on curbing migration through strengthening border controls. Yet, there are several medium and long-term policy alternatives that take into account humanitarian, socio-political and socioeconomic impacts. Based on an analysis of the different drivers of migration along the trail and by exchanging knowledge and expertise on a broad range of migration issues, this living analysis gives an overview of these alternatives and guides policy-makers on the directions they can be heading.

Contents

1. The situation: migration to Europe in 2015

Graphs: Arrivals via the Mediterranean routes

Table: EU border crossings

Most frequent migration routes

Migration to and from Europe: an interactive map

2. Structural and temporal drivers of migration

A long term problem

Table: Motives for migration

3. What is causing the influx?

Changing expectations of Syrian refugees

Migration inside Africa

4. Smuggling economies flourish

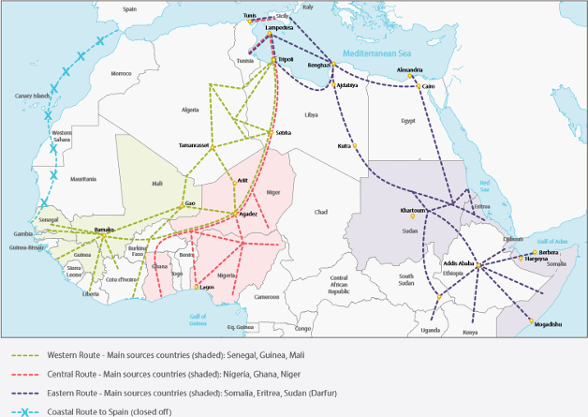

Map: Main migration routes in Africa

The political economy of migrant smuggling in the Sahel

Reports: ‘Smuggled Futures’ and ‘Survive and Advance’

5. ‘Fortress Europe’ policy responses

United Nations and European Union migration regulations

Turkey as gateway instead of safe stay

Prospects of the Valetta Summit

Border controls in Europe

Video: Statement on strenghtening European borders

Report: A Migration Crisis? Facts, challenges and possible solutions

6. Scenarios for Europe’s response

EU’s self-threatening border control

Circulair migration policies tend to focus on return

Integrated and cooperative migration policies and partnerships

The challenges of border security management in the Sahel

Migration and the SDGs

Directions for European immigration policies

Although most migrants still arrive in Europe by air, catastrophic scenes are being played out along several alternative migration routes giving rise to political challenges. The analysis breaks down the different stages and policy challenges along the migration trails.Topic for debate include the possible effects of development and military influences in areas of weak institutional strength where the human smuggling industry is flourishing. Further along the chain, destabilizing effects of refugees are examined as people are flowing into Central, South and East Europe, and finally into parts of North and West of Europe.

About this migration living analysis

A living analysis is an innovative and easily accessible way of structuring knowledge. Our vision is to help improve policies in three ways: by making policies more evidence-based, by reporting on changing dynamics and by making recommendations on how to anticipate these changes.

We do this by giving an overview of existing knowledge and continuously striving towards an improved and more comprehensive analysis by integrating views of experts. These experts reflect on emerging societal, academic and political trends. In the attached links you will find up-to-date expert opinions, research articles, data, videos and an overview of relevant academic and policy reports, literature and media coverage. To join our analysis or to become a partner in the Migration Trail, please contact karlijn@thebrokeronline.eu.

This living analysis starts by looking at the current migration situation in Europe and how migrants travel to Europe (Section 1). It then analyses the driving forces behind migration, the development of the two important routes in the Sahel and the Balkan, and the smuggling economies that flourish along these routes (Sections 2, 3 and 4). Finally, it discusses current European policies as well as possible scenarios for a new European direction (Sections 5 and 6). You can click on the table of contents above to go directly to one of these sections.

This living analysis looks at the irregular migration routes that operate outside the regulatory norms of the sending, transit and receiving countries. An overview of the terminology used in the living analysis can be found by clicking the icon on the left.

Definitions and terminology used

In order to provide a clear analysis of current international migration flows and policies, clear definitions are required. Some of them are explained here:

Irregular migration is a broader concept in comparison to illegal migration or undocumented migration. Irregular migration has the ability to both analyse the stocks and flows of migration, while illegal or undocumented migration are concepts which can only be used to describe stocks of migrants (Koser, 2005). Moreover, most organizations working on issues of migration use the term ‘irregular migration’, including the International Labor Organization and the International Organization for Migration. For these two reasons, the term irregular migration is used in this living analysis.

Although both trafficking and smuggling are considered criminal activities, the differences between the terms lie in the meanings and purposes. Trafficking involves the use of force, abuse, deception or other forms of action against the will of migrants. Moreover, the purpose of trafficking does not have to be financial profit alone but also sexual exploitation, forced labour or slavery (Triandafyllidou and Maroukis, 2012). Smuggling on the other hand can be a free agreement between smuggler and migrant. The migrant may consider the cooperation beneficial because the person needs the smuggler’s services. In order to use a broader term to refer to organized migration with the help of specialized agents, we use the term smuggling rather than trafficking unless explicitly referring to forced and abusive smuggling. Please access more definitions by clicking the link: Read more.

1. The situation: migration to Europe in 2015

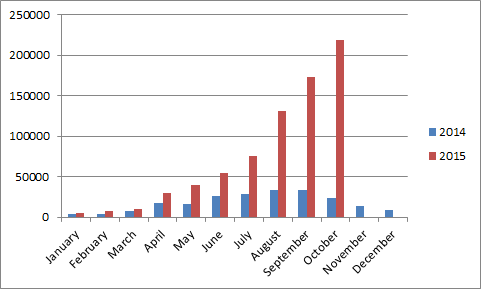

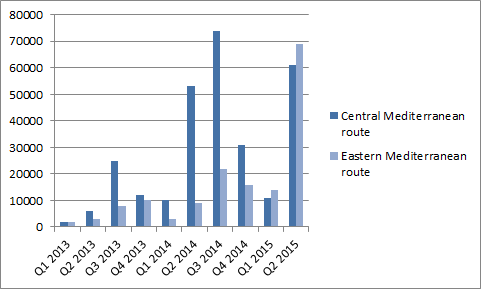

Recent migration developments present a challenge to European countries. Europe will probably record more than one million asylum applications in 2015; up to 450,000 are expected to obtain the status of ‘humanitarian migrant’. From January to August 2015, Frontex detected more than 500,000 illegal border crossings to Europe – nearly twice as much as 2014. UNHCR data show an increase in the use of the three routes over the Mediterranean Sea to over 200,000 irregular migrants in October (see Graph 1 by clicking on the icon to the left). Initially, migrants from both Africa and the Middle East mainly used Libya as the country from which to cross the Mediterranean Sea. In early 2015, migrants mainly used both the Eastern and Central Mediterranean routes (see Graph 2 – by clicking on the icon to the left), but in October 210,000 of the 218,000 migrants who reached the Mediterranean crossed the border from Turkey to Greece. This influx into Europe is still relatively low compared to the total number of refugees, particularly in the Middle East. Since March 2011, 4.3 million Syrians alone have been registered as refugees, of which approximately 3.5 million are in Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq and Turkey.

Graphs: Arrivals via the Mediterranean routes

Graph 1. Total arrivals via Mediterranean Sea 2014–2015 (source: UNHCR, 2015)

Graph 2. Use of Central and Eastern Mediterranean routes 2013–2015 (source: Frontex, 2015)

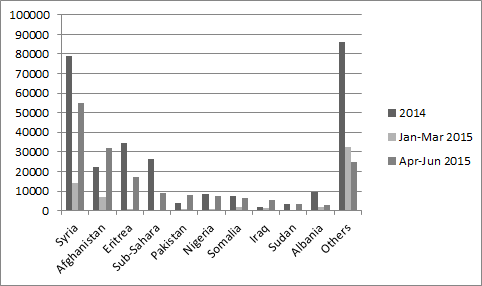

Graph 3. Amount of immigrants to Europe by nationality in 2014-2015 (source: Frontex, 2015)

Illegal border-crossing to European Union (EU) countries take place mainly via seven routes. An overview can be found below.

Table: EU border crossings

Table 1: Route taken by irregular migrants to the EU 2014–2015 (source: Frontex/UNHCR, 2015)

| Route | Country of departure | Country of destination | Main nationality of users |

| Central Mediterranean route | – Libya

– Egypt |

– Italy (Lampedusa)

– Malta |

– Eritrean

– Somali – Syrian – Afghan – Nigerian – Ethiopian |

| Eastern Mediterranean route | – Turkey

– Egypt |

– Greece

– Bulgaria – Cyprus |

– Syrian

– Afghan – Somali – Iraqi |

| Western Balkan route | – Albania

– Bosnia and Herzegovina – Kosovo – Serbia – Montenegro – FYR of Macedonia |

– Hungary

– Croatia |

– Kosovar

– Syrian – Somali – Afghan |

| Western African route | – Senegal

– Mauritania |

– Canary Islands | – Guinean

– Moroccan – Gambian – Senegalese |

| Western Mediterranean route | – Morocco

– Algeria |

– Spain

– France – Italy – Andorra |

– Syrian

– Guinean – Algerian – Nigerian |

| Circular route | – Albania / Greece | – Albania/ Greece | – Albanian |

| Eastern borders route | – Belarus

– Ukraine – Moldova – Russian Federation |

– Poland

– Slovakia – Hungary – Romania – Finland – Baltic states |

– Vietnamese

– Afghan – Syrian – Somali |

Over the last few months, the most frequently used routes have been the Eastern Mediterranean route and Western Balkan route. Most of the irregular migrants to Europe in 2015 have been of Syrian, Afghan or Eritrean descent. This route involves a move to Turkey first, from where migrants continue to Europe via Greece and the Western Balkan countries. You can find more information on these recent dynamics by clicking the icon to the left.

Most frequent migration routes

Migration flows in 2015

Data from the European external border agency Frontex shows an influx along the Eastern Mediterranean route and the Western Balkan route, while the amount of migrants using the other five routes has remained relatively stable. In the second quarter of 2015 from April to June, Frontex reported a 260% increase of Syrian migrants in comparison to the first quarter. The number of migrating Afghans rose 193% during the same period along the Balkan route.

The increased use of the Western Balkan route is a direct result of the increased use of the Eastern Mediterranean route. Many irregular migrants moving from Turkey to Greece or Bulgaria have decided to continue their journey through the Western Balkan route. Due to the costs and danger associated with the Central Mediterranean route caused by the Libyan conflict, Syrians have started to use the Eastern Mediterranean and Balkan route more frequently.

Despite the decreased travelling use by Syrians and Afghans, the use of the Central Mediterranean route has remained stable as more Sub-Saharan Africans migrate along this route for political, security and economic reasons. Mostly Nigerians and migrants from the Horn of Africa including Eritreans, Somalis and Ethiopians travel this route.

The Western Mediterranean route and the Circular route between Albania and Greece can be identified as routes that are primarily used by migrant workers. The usage of these routes has therefore remained rather steady over the past years. For the Circular route, mostly illegal Albanian migrants are traveling back and forth for seasonal jobs in Greece.

2. Structural and temporal drivers of migration

The desire to improve and diversify income is considered the most common driver of migration. But migrants with economic motives mostly stay in their own region (the Middle East or Northern Africa); some move farther as soon as they have the money. Environmentally driven migration, for example as a result of droughts or floods, is also usually a regional phenomenon (a link to the literature study is forthcoming).

A long term problem

There are many reasons why people leave their homes. Some attempt to escape the conflict zones of Iraq and Syria. Others are running away from authoritarian regimes such as Eritrea, but many simply want a new life in Europe as their current life does not offer many social mobility prospects. Many people see themselves as ‘people without value’ considering their lack of prospects and capabilities in becoming ‘real citizens’. Without the option of employment in their home country, land ownership or being able to marry properly, their wish to flee is understandable.

This reality that we are witnessing is not just a temporary phenomenon but a situation we will face for a long time coming. There are many reasons for this current circumstance. The conflicts that produce refugees are not going to end anytime soon and regimes, such as in Eritrea, have proven to have a large capacity of self-preservation. In addition, demographic factors and climate change issues also plays an important role. The Middle East and Africa have the most youthful populations in modern history and these same areas have the most exposure to increased climatic variability threats.

The international migration we see today is primarily motivated by conflict and insecurity. People are fleeing from violence and fear of persecution. Going one layer deeper, researchers have identified underdevelopment, limited access to political processes and horizontal inequality (inequality between groups) as the underlying causes of conflict. Syria’s revolution for more democracy during the 2011 Arab Spring and its violent aftermath of governmental oppression illustrates this.

Insecurity and underdevelopment are, thus, the main push factors for people to move elsewhere. Combine this wth the pull factors of freedom and employment opportunities and we see what drives migration. But other factors determine how far people go and what route they take, including social, environmental and infrastructural factors.

Table: Motives for migration

Table 2 outlines the possible factors for migration. It outlines six types of factors, and distinguishes between three types of countries to outline how these factors are in play in different areas.

Although all possible factors are included in this table, this does not mean they are equally in play. The living analysis will provide insight in the extent to which factors are in play in different spatio-temporal contexts.

Table 2: push and pull factors of migration

| Push factors (countries of origin) | Pull factors (transit countries) | Pull factors (countries of destination) | |

| Economic factors | – Lack of job opportunities

– Lack of income – Lack of ownership of resources (e.g. land) |

– Employment opportunities

– (Portability of) social security and remittances – Quality/access to education |

|

| Security/

political factors |

– Fear of prosecution because of religion, sexuality, ethnicity or political beliefs

– Presence of (civil) wars, terrorism or ethnic conflict – State violence and repression – Foreign military intervention – Lack of opportunity to join a military force |

– Threat of physical violence | – Perception of freedom

– The presence of a stable, non-violent, democratic government – Peace and (perceptions of) security |

| Environmental

factors |

– Drougths and water scarcity

– Floodings or other natural hazards – Lack of fertile land |

– Temperature

– Occurrence of natural hazards |

– Attractive climate and surface

– Fertility of land |

| Legal factors | – Favourable migration laws and policies | – Favourable migration laws and policies | – Favourable migration laws and policies |

| Infrastructural/

physical factors |

– Knowledge about migration routes

– Money to pay fares – Security of migration route – Little presence of physical borders |

– Availability of roads

– Surface of area – Transport possibilities – Presence of smugglers or traffickers |

– Availability of roads

– Surface of area – Transport possibilities |

| Social factors | – Level of community organisation

– Migration history – Level of affection for place of origin – Amount of time lived at place of origin – Intra-household structures |

– Social networks

– Cultural linkages |

– Possibility of reunion with families, friends and relatives

– Cultural linkages |

3. What is causing the influx?

But what has changed to cause the influx of 2015? Irregular migrants mainly come from two regions: the Middle East and Northern Africa.

In the case of the Middle East, conflicts in Afghanistan, Palestine and Syria are the main drivers of migration. However, different motives and perceptions come into play in the choice of where to migrate too. Initially, most refugees flee to neighbouring countries: Afghans go to India, Pakistan and Iran, Palestinians go to Lebanon and Jordan, and Syrians go to Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan and Iraq. However, in 2015 many Syrians and Afghans are continuing their journey to Europe. Part of the explanation is that refugee camps and informal settlements in neighbouring countries are overcrowded, putting enormous pressure on national budgets and individual savings for housing and education. UNHCR reported in June 2015 that programmes implemented by the UN and NGOs for refugee camps in neighbouring countries faced a current funding gap of a US$3.47 billion. Syrian refugees are missing vital support for basic services. In search of a better future, knowing that the war in Syria will not end soon, many Syrians have decided to continue to Europe along the Balkan route. This is argued by van Kesteren. A link to his article can be found by clicking the icon to the left.

Changing expectations of Syrian refugees

The year 2015 marked the greatest influx of Syrians to Europe ever recorded. There is little doubt about the danger of the conflict in Syria as the main driver for emigration, but the motives to migrate to Europe can be debated. With the civil war in Syria lasting for five years already, the main question is not why Syrians have decided to seek refuge, but why they have decided to move to Europe now. The opportunities for a better life in Europe must be recognized as a pull factor, but one push factor should not be overlooked – the changing aspirations and expectations of a return to Syria. Read more.

This is one of the co-authors of the living analysis.

In the case of Africa, the causes of migration to Europe are mixed and less explosive than from the Middle East. On the one hand, conflicts in (South) Sudan, Eritrea and Nigeria have led many from these nations to move to other nations. However, migrants using the Central Mediterranean route are also, for example, of Guinean and Algerian descent. So it can be argued that both economic and security motives come into play in the decision to migrate. Another important, though ambiguous, factor is population growth in Africa, which leads many young, well-educated youth to search for opportunities elsewhere. Historically, most African migration takes place within the continent. Migration to Europe generally occurred only between countries with bilateral connections (such as Algeria and France or Ghana and the Netherlands) or in response to an ongoing civil war (e.g. Somalia). For the last two decades Libya has been the main starting point for African refugees and migrants crossing the Mediterranean. Between 65,000 and 120,000 Sub-Saharan Africans enter the Maghreb each year, of which 70–90% migrate through Libya and 20–30% through Algeria and Morocco. Please find more insights on the drivers of African migration by clicking the icon to the left.

Migration inside Africa

Al-Qadhafi’s pan-African policy, Libya’s oil wealth and the need for foreign workers to maintain Libya’s socioeconomic status resulted in an increase in Sub-Saharan immigration by the end of the 1990s. Networks of migrants provided their countrymen with shelter, information and support in the migration process. In cooperation with Libyans, immigrants started providing transport by boat to Europe.The civil war in Libya, which has been going on since 2011, has not significantly reduced Sub-Saharan migration to the Libyan coast. The brutal force of rival groups and the overall insecurity makes the trip through Libya dangerous, but it still is more attractive than traveling through neighbouring countries like Algeria where migrants and traffickers face heavy fines and prison sentences if apprehended. Read more.

Historically, African refugees move mostly within their own countries or to neighboring countries, because of the proximity and cultural linkages. The shift to large-distance migration patterns within or outside Africa we see today have three different explanations. First, the rise of migration within Africa is partly the result of policies aimed at free movement, such as the ECOWAS in West-Africa. In parallel to the economic development in these nations, many have moved to Ghana, Cote d’Ivoire and Nigeria to work there. Not all are able to find (decent) employment, either because of a lack of rights (residences, employment rights, etc.) or a lack of jobs in general. Particularly the many youth in Sub-Saharan Africa see little opportunities in terms of decent employment, which leaves many to search jobs elsewhere.Second, the rising middle class in many African nations provides more Africans with the money needed for a long distance journey. As argued by Paul Collier the propensity to migrate is highest for the economic middle class. In comparison to lower economic classes they possess the means to migrate, but as opposed to higher economic classes they also still have the incentive to look for better opportunities elsewhere. Finally, the possibility to migrate is increased by the professionalized organisation of smuggling networks in particularly Mali, Niger, Sudan and Libya. These examples show that curbing in migration to Europe requires curbing in migration inside Africa, which in turn requires a comprehensive approach. Read more.

These are co-authors of the living analysis.

4. Smuggling economies flourish

Both migrants from the Middle East and Northern Africa depend on smugglers for travel to Europe. Nearly all of the overland international migrants have paid a smuggler. With the influx of migrants to Europe over the two most important routes (Central Mediterranean and Eastern Mediterranean/Western Balkan route), smuggling has become a booming business. Both routes have several similar characteristics, which might explain why these routes have emerged as the most important migration routes. Limited border controls, fragmented policies and corruption make the borders along these routes easy to transit. Organized criminal networks operate along both routes and the smuggling of goods, people and drugs (heroin via the Balkans and cocaine via West-Africa to Europe) has become an increasingly attractive opportunity for unemployed and marginalized communities.

In the case of the Balkans, historically, there has always been smuggling and banditry. The Wilson Centre reports that the smuggling of heroin from the poppy fields of Afghanistan through South Eastern Europe has flourished under mainly Turkish entrepreneurs. The fall of the communist regime led to the demise of strong border defences, the collapse of police forces, and a lack of central authority. A ‘burgeoning underworld’ emerged in which criminal organizations formed strong ties with law enforcement officials. Massive unemployment made the smuggling industry in goods, narcotics and sex appealing. Frontex reports that, after arriving in the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, migrants typically make use of an ‘open taxi’ system, which profits significantly from smuggling people to the Serbian border.

Map: Main migration routes in Africa

Figure 1: main migration routes in Africa (source: Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime, 2014)

Similarly, in the Sahel-Sahara, the main trail through Africa, border crossings are often facilitated by existing trade and migration networks that date back to the pre-colonial (and pre-nation state) era. You can read more about this below.

The political economy of migrant smuggling in the Sahel

Porous borders, governance deficits and environmental challenges have undermined the effective control of the Sahel’s frontiers. The response by governments to implementing these provisions has been mixed due to a variety of factors, prominent among them are lack of political will and resources. This has resulted in a gap between policy and implementation, according to the Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre in a contribution to Sahel Watch. The transnational criminal networks in Libya are now estimated to be worth upwards of US$323 million a year, and are deeply impacting on stability in the region. This illustrates the fact that many people benefit from migration. Alongside more fierce approaches to counter smuggling, economic alternatives should be sought for the people dependent on it for their livelihood. Read more on this in Section 6 ‘Scenarios for Europe’s response’.

Reports: 'Smuggled Futures' and 'Survive and Advance'

5. ‘Fortress Europe’ policy responses

As a response to the influx of irregular migrants, many European governments, Schengen and non-Schengen, have started to reformulate their migration policies, strengthen border controls and even temporarily close their borders. Member states are revising their approach at the national level, reflecting a lack of coherency at the European level. As such, national policies are challenging the fundamentals of the European Union and the cooperation of ‘Fortress Europe’ as a whole. Read more about this below.

United Nations and European Union migration regulations

The Migration Trail living analysis focuses on directions and improvements of European migration policies. To do so it is important to outline first how these policies are embedded within international regulations. This slide outlines some of the most important regulations on migration at the level of the European Union and United Nations.

EU asylum policies:

- Dublin regulation (2013)

- Temporary protection directive (2001)

- Directive for minimum standards of the reception of asylum seekers (2003)

EU immigration policies

- Schengen borders code (2006)

- Visa code (2009)

- Directive on trafficking in human beings (2011)

- EUROSUR regulation (2013)

- Directive on common standards and procedures for return of illegally staying third-country nationals (2008)

UN regulations:

- The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948)

- The Convention and Protocol Related to the Status of Refugees, more commonly referred to as the Geneva Convention (1951)

- International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families (1990)

- Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons (2000)

- Protocol Against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air (2000)

Please access more information on the migration regulations by clicking the link: Read more.

At the European level, four priority areas can be identified, based on the end statements of the six European Council meetings on migration in 2015. These are the strengthening of border controls, relocation of migrants, cooperation with third countries, and return and readmission of migrants. The strengthening of border controls can be achieved through the strengthening of the EURODAC fingerprint mechanism, the implementation of new technologies and the strengthening of Frontex. The relocation of migrants is now facilitated through ‘hotspots’: reception centres installed by Frontex in Greece and Italy to identify and fingerprint migrants. Cooperation with third countries – specifically cooperation with Turkey and countries in Africa – can be increased to limit migration to Europe by tackling the root causes of migration, as well as for the return and readmission of migrants to Africa and the Middle East.

Turkey as gateway instead of safe stay

Turkey is now host to the largest number of refugees of any country in the world, at 2.1 million. This is primarily made up of Syrian refugees, but also a sizeable number of Afghans, Iraqis and Iranians. Turkey is currently the primary gateway to Europe as migrants travel to Greece through Turkey. As such, the country has a dual role – coping with the mass influx of refugees and dealing with the pressure exerted by its European neighbours to curb migration flows to Europe.

Turkey is a signatory to the 1951 Geneva Convention, but with a geographical limitation requiring Turkey to only grant refugee status to people coming from Europe. Therefore, the current caseload of refugees in Turkey are either processed by UNHCR or, in the case of Syrians and Iraqis, given temporary protection by the Turkish government. As a destination country, Turkey has extended multiple services to help cope with the primarily Syrian refugees. Over 260,000 Syrian children are now enrolled in Turkish schools (roughly a third of all Syrian children in Turkey). Turkey has permitted Syrians free access to education and health care and should be commended for their welcoming stance on refugees. Read more.

This is one of the co-authors of the living analysis.

Although Europe has intensified its cooperation with third countries, the Valletta Summit in November 2015 exposed the lack of unity among European members states. Moreover, the focus during the meeting was almost exclusively on the voluntary or forced return of migrants to Africa, with many of the concerns and ideas raised by civil society left undiscussed, criticized by van Dillen. Read this critique by clicking the icon to the left.

Prospects of the Valetta Summit

The Valletta Summit resulted in a Political Declaration, an Action Plan and a new Trust Fund. The Declaration and Action Plan are full of vague language and repeating agreements that have already been signed elsewhere such as the commitment to reduce the transaction costs of remittances to below 3% by 2030, which was already agreed upon in the Financing for Development conference in July 2015. The Trust Fund will provide two billion euros for implementation in 25 African countries. The financial resources pooled by the European Commission were not met by any substantial figures from the EU member states. African leaders themselves also failed to commit to substantial financial contributions, with a minimum of three million euros allowing them to share ownership and co-management of the Trust Fund.

It would in fact be a mistake to channel the resources of the Trust Fund to government programmes. Instead the resources should be provided to civil society and small and medium enterprises, or social business actions in the countries involved. Governments should concentrate on establishing an enabling environment. With Valletta, there was no inclusive governance process and civil society organizations have been excluded until the eleventh hour when two representatives were allowed to participate as ‘observers’. As with much of the Valletta Summit process and outcomes, this was ‘too little, too late’.

This is one of the co-authors of the living analysis.

The Valletta ‘European response’ to the migration crisis was a dual effort to promote the return of migrants and prevent them from coming. When putting the recent EU policy developments into a legal-historical perspective, it is clear that existing regulations are at stake. The regulations currently under debate are the EU Dublin Regulation, Schengen Borders Code and UNHCR Geneva Convention. The ‘first country of entry-principle’ of the Dublin Regulation has been challenged by the European Parliament’s allocation key. This resolution proposes a permanent, binding system for distributing asylum seekers among member states, to replace the Dublin Regulation under which responsibility falls on the country of first entry (usually Greece or Italy). Germany, Hungary and the Czech Republic have already declared that they will suspend the Dublin Regulation and manage their applications themselves directly.

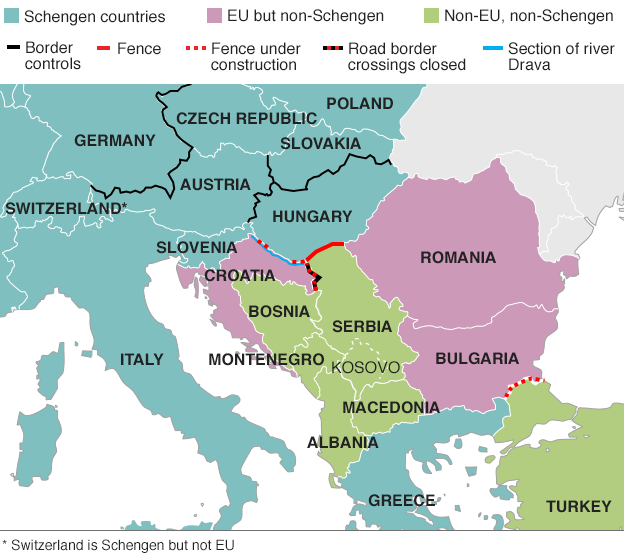

Border controls in Europe

Figure 2. Border controls in Central and Eastern Europe (source: BBC, 2015)

The future of the Schengen agreement has been called into questioned by the closure of national borders in response to the influx of irregular migrants. Can the Schengen Treaty hold up under these developments? And, if so, what needs to be done to strengthen the borders. President Tusk of the European Council has already warned that effective procedures for registration of migrants are essential for the future of the Schengen Treaty.

Video: Statement on strenghtening European borders

Statement of the President of the European Council on the measures agreed to strengthen European borders. Policy proposals are: the full adoption and increased empowerment of Frontex, cooperation with African partners (in Valletta, Malta in November) and discussion of the continuation of the Dublin Regulation, use of ‘hotspots’ and improved coastguard systems.

The Geneva Convention is also called into question, not because of its definition of ‘refugee’, but because of the responsibility imposed by the Convention on the country that a refugee flees to. Article 34, for instance, states that nations should facilitate the ‘assimilation’ and ‘naturalization’ of refugees, which has a broader meaning than mere (legal) protection. The question, therefore, remains: What does the Convention mean and can this broader interpretation of a nation’s responsibilities be maintained, particularly as the EU Action Plan on returning irregular migrants contravenes the Convention’s principle of non-refoulement. Moreover, nations such as Turkey can use the limited geographical scope of the initial Convention (the 1951 version only refers to people fleeing as a consequence of ‘events occurring in Europe’) to abstain from taking responsibility for refugees from places such as the Middle East or Africa.

Debates on the meaning and usefulness of the regulations are partly grounded in their vague formulations. The Visa Code, for instance, obliges countries to grant limited territorial validity (LTV) visas based on ‘humanitarian grounds’, although these grounds are not defined in the Visa Code nor in the Schengen Borders Code.

Report: A Migration Crisis? Facts, challenges and possible solutions

6. Scenarios for Europe’s response

The pressure on the Dublin Regulation, Schengen Treaty and Geneva Convention means that Europe needs to revise its vision and strategy. Potential approaches vary from an inward looking strategy, in which each of the member states seeks to save only its own backyard (halting or even reversing the process of European unity), to a more forward looking approach in which members work together to address the migration situation. The experts that have contributed to this analysis point to four possible directions (scenarios) in which European policy might head.

1. Back to the nation state:

In the first scenario, European leaders follow the right-populist electorate: the external and internal borders of Europe are closed and the Schengen Treaty is declared untenable. See, for example, the statement of President Tusk of the European Council below. The recent Western European alliance – Austria, Germany and the Benelux – is already a step in this direction. Under this scenario, countries like Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan would obtain financial support to retake migrants. Please read an analysis of the consequences of this scenario by clicking the icon to the left.

EU's self-threatening border control

Henk van Houtum and Rodrigo Bueno Lacy

The EU’s current border ideology follows the assumption that stricter visa rules, higher walls and unwelcoming reception systems will dissuade future migrants. The EU has built and keeps reinforcing a discriminatory mobility system based on where people are born. This creates a geopolitical division between travellers who require a visa (mostly Muslims and people from developing countries) and travellers who do not. Rather than looking at the intrinsic value of the individual—regardless of their place of birth—, this system resorts to cartographic prejudice to decide who gets a chance and who does not. The repercussion of this distinction is the criminalization of the very principle of mobility and openness that has been the most powerful force behind European integration over the past 64 years. The natural desire to move has been turned into an illegal activity which, in turn, fosters other criminal industries by diverting the travellers unable to obtain a visa towards more dangerous and often deadly routes. Read more.

These are co-authors of the living analysis.

2. Selecting at the gate:

A second scenario is to create incentives for economic integration and minimize political integration. In this scenario, member states invest in national transit centres, based on the German example, to enable them to select migrants based on the economic added value of the migrant. Temporary work permits, the so-called ‘Blue Cards’, would be granted to immigrants who can be used in areas where there is a labour shortage. Under this scenario, distrust of European policies dominates, resulting in a mostly national approach to the regulation of migrant flows. Bieckmann, Wijers and Martin point to the potential of circular migration, but also warn for reversive effects in the slide below. Managed circulated migration schemes would require close coordination both between European states, and between Europe and the home (developing) countries.

Circulair migration policies tend to focus on return

Frans Bieckmann and Roeland Muskens:

The argument for freer (circular) migration is partly derived from modern market theories. They assume that, like the free movement of goods and services, the free movement of labour will eventually lead to greater welfare for all, and thus there must be fewer rules and other obstacles to migration. But to get anywhere near a triple win, (international) regulation is essential. In order for circular migration programmes to work, temporary labour must be subject to a number of limitations, says Martin Ruhs of the Centre on Migration, Policy and Society at the University of Oxford. Such programmes require significant government involvement and interventions in the labour market. There must be incentives for migrants to return home after their temporary work permits have expired, as well as clear rules and regulations in order to control the costs of providing services, issuing work permits, etc. Read more.

We need to start looking at migrant entrepreneurship as a multisite, transnational activity situated in distinct institutional contexts. If we link our information on their entrepreneurial activities in host and in home countries in order to find ways to realize their potential, returnee entrepreneurs may be able to make more significant contributions to both host and home economies. Read more.

There is a large gap between the rights of migrant workers stipulated in international human rights, law and the rights that migrants working in high-income countries experience in practice. We should start discussing the creation of a list of universal ‘core rights’ for migrant workers that would include fewer rights than the 1990 UN Convention of the Rights on Migrant workers with a higher chance of acceptance by a greater number of countries – thus increasing overall protection for migrant workers including in countries that admit large numbers of migrants. Importantly, the list of core rights could complement rather than replace the existing UN conventions for migrant workers. Read more.

These are co-authors of the living analysis.

3. Integrating European policies:

In the third scenario, Europe improves its internal policy coherence in order to act more coherently as a united front. Under this scenario, the different directorate-generals of the European Commission frequently come together to exchange knowledge and expertise on a broad range of migration issues, from visa policies to job opportunities, as advocated by the Brussels Migration Policy Institute. Besides the Directorate for Migration, Interior and Civil Affairs, which currently addresses migration, there will be a special envoy for migration in the diplomatic service of the EU (the European External Action Service), which will represent the EU in negotiations with non-member states. Under this option, the EU will strengthen its international relations with the Middle Eastern and North African countries (MENA) where there is a lack of migration policies.

This third scenario provides opportunities for international organizations to improve inclusive governance. As argued by Sarah Wolff, international organizations can contribute to inclusive governance of migration by working at multiple levels, share out of the box-insights and promoting a global and transnational approach.

Integrated and cooperative migration policies and partnerships

The EU migration and refugee crisis has acutely revealed the limits of the Schengen and Dublin systems as well as national reticence to build a European migration and asylum policy. By pointing at the failure of EU migration governance, International organisations (IOs) are legitimizing their potential added value in order to improve migration governance towards gentler and better policies fostering international cooperation that are respectful of migrants rights. Here are a few of Sarah Wolff’s recommendations:

- Promote IOs’ expertise and knowledge. IOs palliate the deficiencies of EU staff, for instance within the EEAS. Very few delegations have migration or asylum experts. Training EU officials at headquarter and country level could help spread that expertise more widely.

- Multi-level advocacy strategy. Since EU member states are the main gatekeepers, headquarter advocacy could extend more towards members of the European Parliament, a strategy that UNHCR has already implemented.

- Promote a transregional approach. Namely, work on the relevance of adjacent regions to the Mediterranean, in particular the arc of crisis in the Sahel-Sahara. IOs and EU need to work together with Mediterranean partners to develop sub-regional strategies.

- Capitalise on global membership. The current crisis does not merely concern Europe and its MENA neighbours. IOs can capitalise on their wide membership to advocate different policies from the Gulf countries or even the United States.

- Widen cooperation with Frontex. This should apply to border management, training and scrutinising guards’ activities. This would foster a socialization of EU border guards to international legal norms.

- Ensure the EU and Mediterranean partners reform their migration and refugee policies. This could be done via specific task forces that could foster national dialogue with beneficiary countries. Read more.

Anna Knoll, Raphaëlle Faure & Mikaela Gavas:

Three constraints underpin this lack of coordination: the EU’s system of shared competences, the number of actors involved from different areas and with conflicting interests, and the fragmentation of existing programmes at the national level. Several steps can be taken to overcome these constraints, but they require a shared understanding that a joint EU response is essential. Read more.

Fiederycke Haijer & Jeff Handmaker:

To effectively deal with migration, the European Union needs to improve its use of extraterritorial jurisdiction in two fields: corruption and international crimes. Read more.

Eugenio Cusumano points to new roles for NGO’s in humanitarian crises such as the drowning of refugees in the Mediterranean Sea. As a result of activism, new technologies, new funding opportunities and partnerships, NGOs like the Migrant Offshore Aid Station have been able to take a lead role in rescue operations. Particularly its innovative technologies provide an example for other charity organisations. Read more.

Manon Tiessink and Franca König:

Tiessink and König point to the ‘management crisis’ Europe is facing. According to them, the key to success and effectiveness of migration policies lies in inclusive coordination, cooperation and partnerships on and between all levels of governance. Read more.

These are co-authors of the living analysis.

The EU can also upgrade its external diplomatic relations with its regional partners, including Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), in developing border management. You can read more on this by clicking the icon to the left.

The challenges of border security management in the Sahel

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) has formulated policies in a bid to control the security challenges encountered. All these have sections devoted to cross-border initiatives, the strengthening of border controls, migration and counter-terrorism. While they indicate an awareness of the challenges on the ground, in reality not much critical capacity or resources have been developed or devoted to make them operational. African governments across the region can start addressing the border crisis by:

- developing national border management policies across the ECOWAS sub-region, as has been done in Benin and Senegal;

- raising awareness about relevant legislation, instilling ethics, and increase border security training programmes for state agencies to boost professionalism; and

- prioritizing the development of infrastructure in border areas by governments to reduce reliance on, and threats from, sub-state actors. Read more.

Since 2004, the EU has introduced a number of cooperative projects in Libya to fight illegal migration (such as Across Sahara I, II, SaharaMed, TRIM, AVRR, TAIEX), financed border surveillance, the repatriation of migrants, technical assistance, and training on human trafficking, and supported the erection of detention camps. But in fact Libya was not effective at preventing irregular migration to Europe. The EU would be better off fighting the root causes of migration. What is needed is true support for West African states by curtailing European and multinational companies (such as the nuclear energy giant Areva in Niger) and strengthening democratic structures (instead of flattering compliant dictators). Read more.

These are co-authors of the living analysis.

4. Towards an international orientation:

The fourth scenario is implementation of an approach that removes the root causes of migration. European leaders set a common strategy that builds on internationally signed UN and EU treaties. An example includes the 2000 Protocol against the smuggling of migrants by land, sea or air, which ‘pays special attention to economically and socially depressed areas, in order to combat the root socio-economic causes of the smuggling of migrants, such as poverty and underdevelopment’ (Article 15(3)). The Sustainable Development Goals provide a framework that European leaders can use for such an approach.

Migration and the SDGs

In the context of the ongoing debates about how to manage the impacts of mass migration, the 2030 Agenda should be seen as a critical framework for guiding international action. On the one hand, it offers a way of effectively managing migration-specific challenges, particularly by calling for the implementation of planned and well-managed migration policies. On the other hand, it also addresses broader structural issues, such as poverty, inequality, lack of access to health, employment and education, peace and justice and so on, all of which are deeply connected to migration and can make migration necessary in the first place. Recognizing the value of the 2030 Agenda in this context is critical to addressing the challenges currently facing Europe, and indeed, many other parts of the world. Giving effect to this agenda in the context of migration requires holistic policy approaches that focus on two broad objectives: addressing the drivers of forced migration and promoting the dividends of migration. Read more.

Household enterprises need to be included in planning processes, cities need to invest in infrastructure for the sector, and governments need to establish transparent zoning and regulations that support sector growth and stability. If this approach is not adopted, poverty will only grow as Africa’s cities expand and urban youth will remain excluded from development. Read more.

These are co-authors of the living analysis.

This aims to improve economic development, access to politics for young people, peace and stability in countries of origin (as advocated for during the Arab Spring) and offers alternative income than smuggling (as advocated by the Kofi Annan Peacekeeping Training Centre). Frontex data shows that more than 80% of the adult migrants were men. Under this scenario, youth employment funds are established for African and MENA countries, as well as socioeconomic programmes in Europe to prevent polarization within Europe. Additional funds target the temporarily increase in migration resulting from economic development in the home country (as a higher income initially allows to fulfil an existing desire to migrate).

Directions for European immigration policies

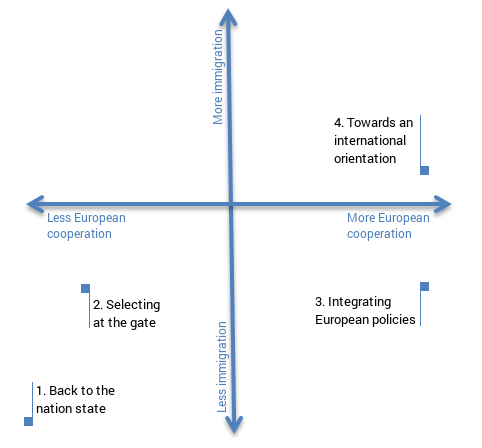

The scenarios above are a way to determine the directions European and national policies may be heading towards. These directions are displayed in the figure below. The policies differ in the extent to which they allow an influx of migrants and to what extent they lean on European cooperation for realizing their goals. It can be seen that the two directions are not related: high European cooperation can be used both for curbing in or for expanding immigration, for instance.

However when placing the different scenarios in this scheme, two things stand out. First, in any type of scenario there is a limitation of the influx of migrants. This can be handled by either increasing border controls, by offering assistance to refugee camps in Europe’s bordering countries or by increasing development aid in general. Generally speaking though, all scenarios are headed towards some limitation of immigration. Secondly and more importantly, European cooperation is at a crossroads: either the European cooperation will be strengthened, comprehended and made more efficient or governments will turn to national policies. Since the fundamental agreements of both the EU and UN are at stake, these agreements will either have to be rejected or revised, and otherwise they will need a stronger implementation.

Figure 3: characterization of different migration policy scenarios

In practice, the solution may lie in a combination of the last two scenarios. The UN and EU treaties show that, on an intergovernmental level, the political will is there to achieve these scenarios. But, in practice, migration challenges are putting so much pressure on EU member states that they are bowing to right-wing populist groups advocating for a short term response that involves putting the iron curtain back in place. These scenarios will be elaborated on during this project as more views of experts are integrated.